It’s hard to believe but the tech-heavy Nasdaq is close to bull market territory.

As research firm Bespoke pointed out last week, the index is up 19% from its closing low on 16 June.

Our own S&P/ASX 200 is up 9% since a closing low on 20 June.

And the S&P/ASX 200 Information Technology Index is up 25% since a low on 17 June.

Are we in a bull market?

Not yet.

Today, I’m going to explain why the recent rally is on borrowed time.

Recent rally on borrowed time

Rising stock prices can be very alluring — as the market moves higher, you naturally think the worst must be over.

Sometimes that is the case. Sometimes it’s not. Instead of just looking at prices and reaching a conclusion, the best option is to simply use common sense.

The commonsense approach today is pretty simple — the US economy is in a recession, yet the Fed continues to hike rates.

It takes a brave or foolhardy investor to think that stocks can sustain a rally in such a scenario.

Alternatively, to justify the rally, you have to think the recession is over, and the Fed is much closer to cutting rates than most investors currently think.

But with headline and core inflation readings still too high, it’s clear to me that the Fed will continue to increase rates despite the recession.

This is a very unusual situation. Usually, when recession hits, the Fed has already reached an interest rate peak and started to cut.

Think back to the lead-up to the GFC.

The Fed stopped raising rates in June 2006. The market peaked in October 2007. The Fed actually started its rate cutting cycle BEFORE the market peaked.

It cut rates by 50 basis points in September and another 25 basis points each in October and December.

Then, throughout 2008, it cut rates all the way to zero.

Yet the market didn’t bottom until March 2009! And the S&P 500 lost 50% of its value throughout the rate-cutting cycle.

What about in the 2000 bear market?

The Fed raised rates to 6.5% by May 2000. The S&P 500 peaked in March 2000 and got nearly as high again in September 2000.

The Fed then cut rates aggressively in 2001, going from 6.5% to 1.75% by the end of the year. Yet the bear market continued. The S&P 500 bottomed in October 2002, nearly two years after the easing cycle started!

This time around, the inflation problem the Fed is facing is much worse than at any time since the 1980s, and it hasn’t even stopped raising rates yet.

How anyone thinks the market has bottomed here is beyond me.

The Fed warns the market

Earlier this week, three Fed officials hit the airwaves to tell the market not to get too excited about the end of rising interest rates.

Federal Reserve officials said they expected to keep lifting borrowing costs through at least early next year to slow the economy and bring down high inflation, pushing back against some investors’ hopes of a milder rate path.

As reported by the Fed’s mouthpiece at The Wall Street Journal, Nick Timiraos:

‘Chicago Fed President Charles Evans told reporters Tuesday that he hoped the central bank would be able to moderate its interest-rate rises over the remainder of the year after increasing rates in unusually large increments at its past two meetings. But he held out the possibility of another supersize rate increase at the Fed’s next meeting on Sept. 20-21.

‘“The kinds of things that would make larger rate increases more important, like in September, would be if you really thought things weren’t improving,” Mr. Evans told reporters at a briefing Tuesday. “I think that there’s enough time to play out that 50 is a reasonable assessment, but 75 could also be OK.”

‘After that, Mr. Evans said he hoped the central bank would be able to continue raising rates in more traditional, quarter percentage point increments at its last two meetings of the year, in November and December, and through early 2023. “In spite of less favorable inflation reports than I expected in June, I’m still hopeful that that rate path is a reasonable one after all,” Mr. Evans said.

‘Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said that with inflation so far above the Fed’s 2% target, she was anxious about prematurely concluding that price pressures were easing.

‘“We have more work to do because we have not seen that turn in inflation,” she said in a webinar with the Washington Post. “It’s got to be a sustained, several months of evidence that inflation has first peaked — we haven’t even seen that yet — and that it’s moving down.”

‘San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said the central bank’s effort to bring down prices by slowing demand was nowhere near done and pushed back against some investors’ expectations that the central bank would pivot to rate cuts next year after raising rates to around 3.5% this year.’

The message here is that the Fed is not happy with the market’s recent interpretation.

They don’t care that the economy is in recession. They only care about getting inflation back down towards 2% and will drive the economy into the ground to get there.

Coincidentally, that’s exactly what former Fed insider Joseph Wang told Callum Newman in a recent Fat Tail podcast.

I recommend having a listen.

Will inflation come down quicker than the Fed expects?

Anyway, here’s something to consider.

Maybe inflation will come back down to the Fed’s target range much quicker than expected?

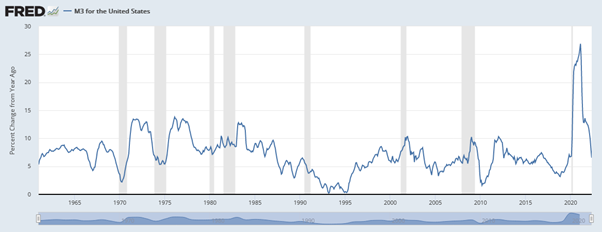

To explain, let me show you a chart of year-on-year M3 growth in the US. M3 is a measure of the growth of ‘money’ in the economy.

As you can see, the COVID response saw annualised M3 growth reach a historic peak of 27% in February 2021. That ‘money’ flowed into the economy and stock market, creating a surge in inflation.

Stock market inflation peaked around November 2021, while inflation in the real economy probably peaked in June 2022.

Source: St Louis Fed

But now, M3 growth is falling fast. Based on the latest reading (from May), annual growth is back down to 6.5%. It will continue falling in the months ahead.

This trend, combined with an ongoing normalisation of supply chains following the COVID disruptions, means that in the months ahead, the rate of inflation will continue to fall.

Oh, and don’t forget, there’s no help coming from fiscal policy anytime soon. The budget deficit is set to shrink year-on-year, which means it will detract from growth.

If the Fed decides to move by 75 basis points in September (unlikely in my view), that will take the Fed funds rate to as high as 3.25%.

In a highly indebted economy, that is contractionary. Even a 50-basis-point increase will contribute to an ongoing slowdown.

The message is that earnings growth will struggle while the Fed waits for inflation to fall.

So the market is being very optimistic in bidding prices up here.

What about Australia and the ASX?

Well, the RBA raised rates by 50 basis points earlier this week.

The cash rate is now 1.85%.

While that’s low by historical standards, it represents a massive 175 basis points of tightening in four months.

Monetary policy works with a lag, so the effects of this tightening will show up in early 2023.

Despite the RBA indicating that it won’t continue to raise rates blindly in the months ahead, there is reason to think they are considerably behind the Fed when it comes to the inflation fight.

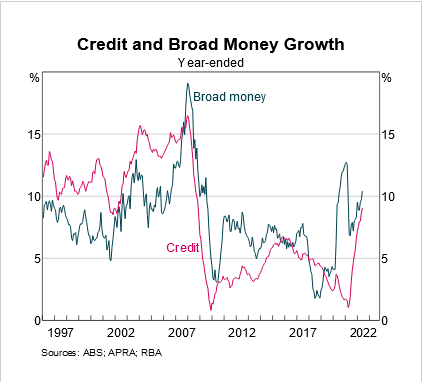

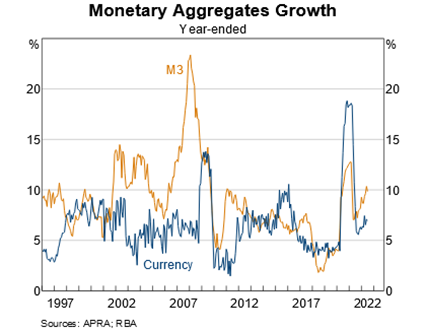

The charts below show Australia’s annualised money growth.

The first one shows credit and broad money growth, while the second one shows M3 and currency growth.

Based on the latest annualised figures for June, broad money growth was 10%, credit growth was 9.1%, while M3 growth was 9.8%.

In other words, money growth is running hot and is yet to turn down. Even the month-on-month figures (which give you a better idea of more recent trends) remain strong.

For June, all three were above 10% on an annualised basis.

Source: RBA Chart Pack

Source: RBA Chart Pack

When you’ve got an inflation problem — that’s way too hot.

These readings should start to come down following recent rate rises.

But it just goes to show how inappropriate the RBA’s prior settings were. Rates were insanely low given nominal economic growth (real plus inflation) has been running at 10%-plus for most of the year.

Again, like in the US, this inflation fight points to headwinds for company earnings.

Because to kill inflation, you have to kill economic growth. Expectations for nominal growth (important for company earnings) are already much lower for this financial year (FY23).

So what to do?

My view is pretty simple.

Own solid dividend payers to keep the income flowing in. Stay patient. Wait for opportunities rather than chase stocks higher.

It’s hard, but in bear markets, you’re better off buying when you’re fearful that prices will fall further rather than buying because you’re fearful that prices will keep heading higher.

I recently put together a bear market survival guide of sorts, detailing what I think investors should do in the current market.

You can read my thinking here.

Cheers,

Greg Canavan

PS: Speaking of dividends, if you want to read a profile on five ASX dividend stocks, you can access our free dividend stocks report here.