As the world moves away from fossil fuels to one increasingly powered by renewables, critical minerals are a crucial ingredient for many of today’s clean energy technologies.

You’ve likely heard all the fuss about them.

But, what exactly are they, and why do we need them?

What are critical minerals?

Geoscience Australia defines a critical mineral as a metallic or non-metallic element that’s essential for the functioning of modern technology, the economy, or national security. What’s more, their supply chains are at risk of disruption.

Something important to note is that what’s considered a ‘critical mineral’ can change overtime as technology advances and societies transform.

For example, after the First World War broke, potash — used for making fertiliser and gunpowder — became scarce. You see, Germany was one of the world’s largest potash suppliers at the time. So potash was considered quite a strategic resource.

Why are critical minerals needed?

Today, many of the resources that make it into a country’s critical minerals list are essential in the manufacturing of modern technologies such as smart phones or semiconductors, in defence and aerospace, and in energy security to produce things like wind turbines, solar panels, and electric vehicles (EVs).

Lithium, graphite nickel, and manganese, for example, are essential components of EV batteries. Rare earths are crucial for making magnets, communications equipment, and things like guidance systems.

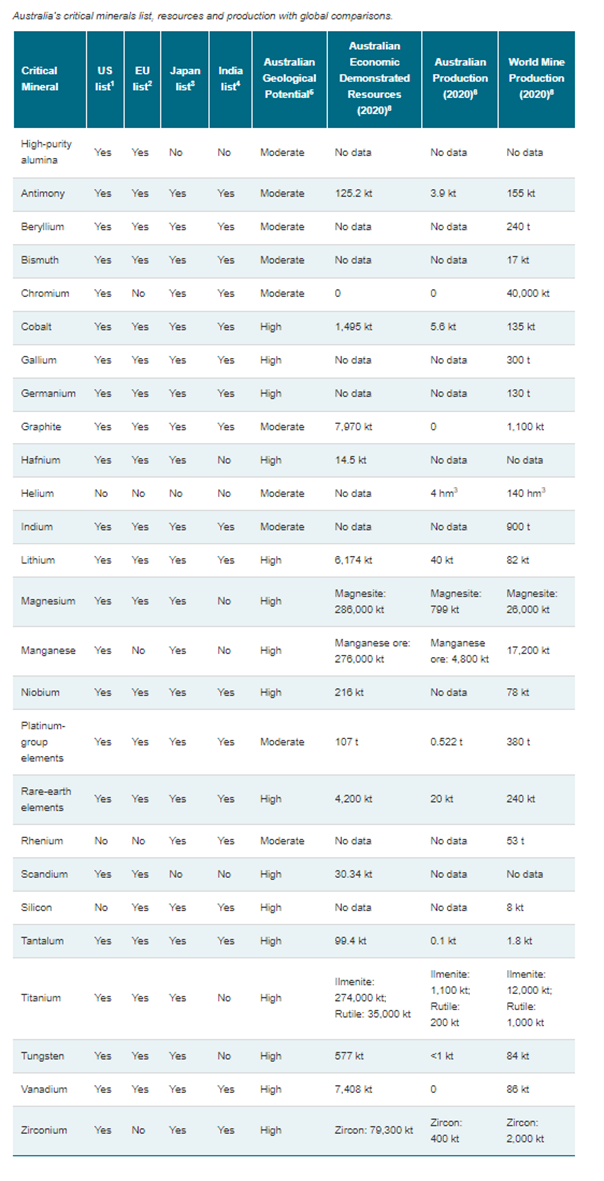

Another thing to mention is that not every country has the same critical minerals on their list.

The EU, for example, has 30.

On the other hand, the US recently listed 50 mineral commodities it thinks are essential to its national security.

At the time of writing, Australia considers 26 resources critical. And as you can see below, not all of them are considered critical minerals by the US, the EU, Japan, or India:

Source: Geoscience Australia

One thing to keep in mind is that Australian domestic demand for these critical minerals is quite small.

Instead, Australia’s strategy when it comes to critical minerals is to grow the sector to help meet global demand.

That is, Australia wants to become a ‘critical minerals powerhouse’.

As the 2022 Critical Minerals Strategy noted:

‘Growing global demand creates a significant opportunity for Australia, thanks to our critical mineral reserves and our reputation as a trusted and reliable supplier.

‘Australia has some of the world’s largest recoverable resources of several critical minerals, including cobalt, lithium, manganese, tungsten and vanadium.

‘Many countries want minerals that are sourced in an environmentally and socially responsible way. Australia has one of the world’s strongest and most efficient regulatory environments, which makes us an attractive supplier of critical minerals products.

‘Becoming a critical minerals powerhouse will support thousands of jobs. Critical minerals projects can help ensure the continued growth of our resources sector and provide high-paying, skilled jobs for Australians, particularly in regional areas and heavy industry hubs.’

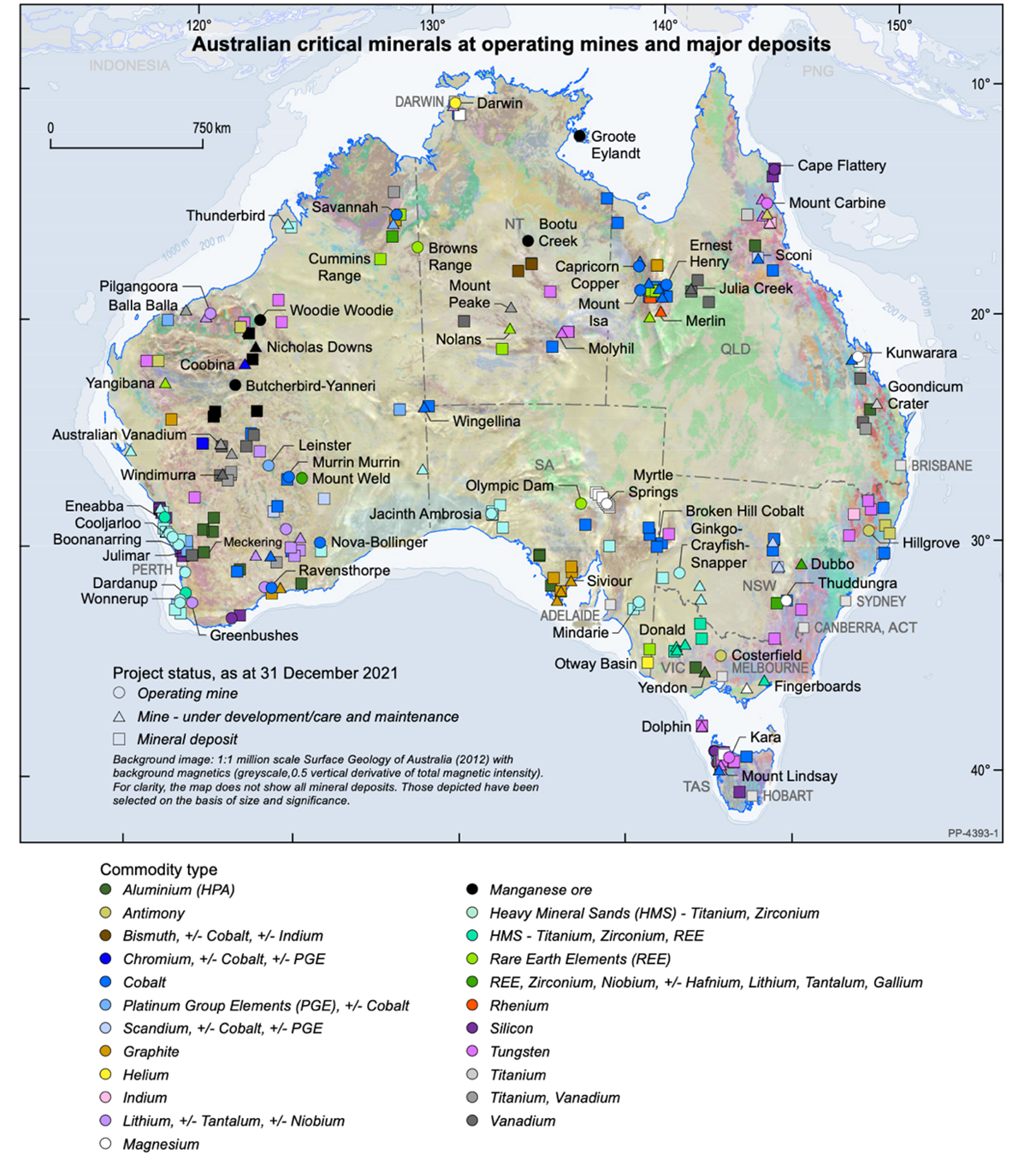

Australia has vast potential for critical minerals, already holding many deposits and mines, as you can see below:

Source: Geoscience Australia

But what’s interesting is that well-established mining regions only make up 20% of Australia. With 80% of Australia very much underexplored, there’s plenty of potential to discover more…

Why demand for critical minerals is expected to grow quickly

One thing supercharging the demand for critical minerals is the energy transition.

In the last few years, this has been accelerating as countries have been increasing their pledges to decarbonise their economies.

But also, the current Russian-Ukraine war has made fossil fuels more expensive and exposed the need for energy security. So countries have been boosting renewable power as a way to strengthen their energy security.

Furthermore, solar, wind, and batteries have become increasingly cheaper in the last 10 years. In fact, the International Energy Agency has even gone as far as to crown solar as the cheapest energy ever.

So shifting to renewable energy also makes economic sense.

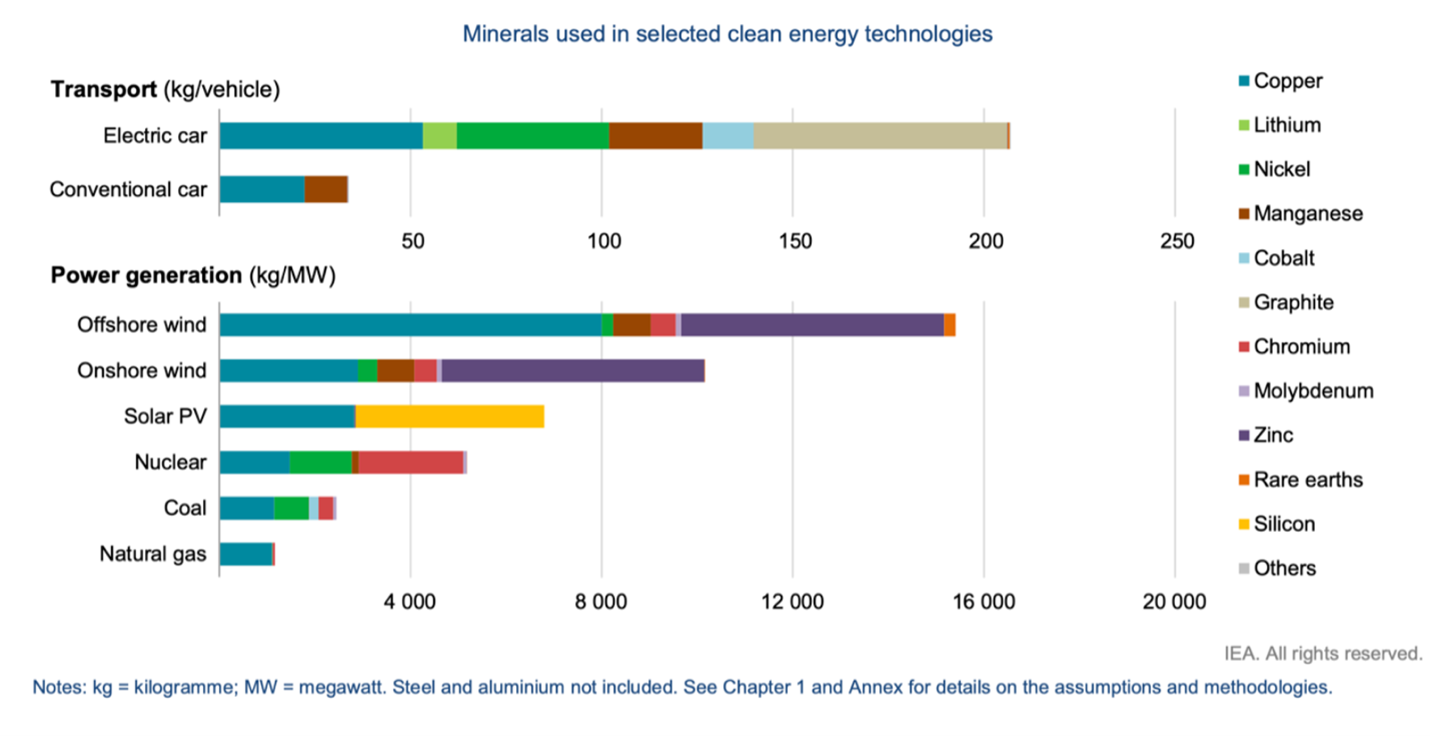

And EVs, solar panels, and windmills need plenty of critical materials.

Just to give you an idea, let’s look at what goes into an EV battery.

While amounts will vary depending on type, a typical EV battery holds around:

….11.3 kg of lithium…

….13.6 kg of cobalt….

…27 kg of nickel…

…50 kg of graphite…

…and 40 kg of copper, along with other stuff like steel, aluminum, and other components.

And that’s just one battery.

EVs, windmills, and solar panels all use more critical materials than internal combustion vehicles or coal and natural gas power generation, as you can see below:

Source: Earthshiftglobal

So as the energy transition accelerates, we’re going to need plenty of critical minerals…a staggering amount of them in fact.

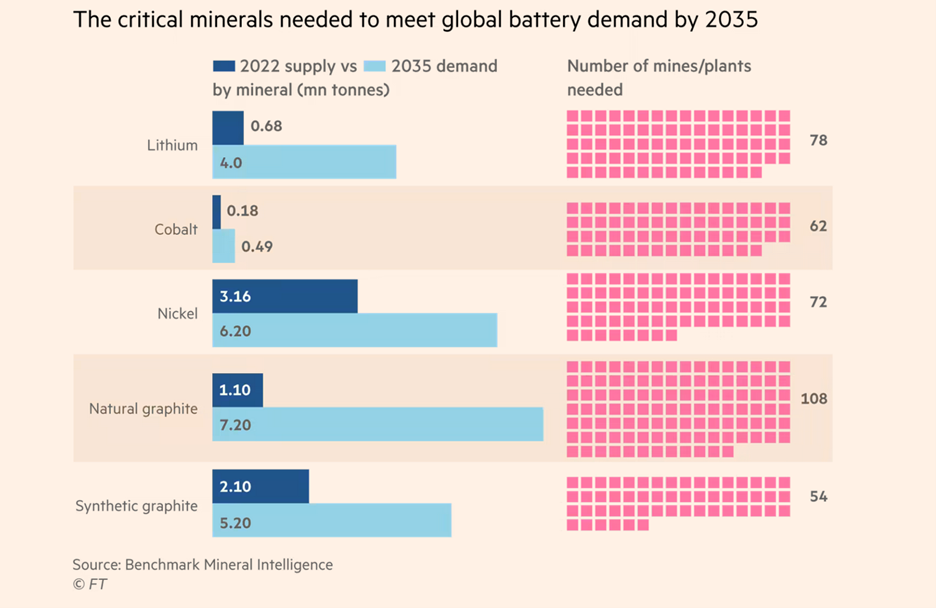

Just to give you an idea, it’s estimated lithium supply will need to grow almost sixfold, nickel supply will need to double, and natural graphite will have to increase 6.5 times by 2035 to meet demand, according to Benchmark Minerals.

And, as you can see below, we are going to need more mines also:

Source: The Financial Times

Remember, discovering and developing a mine takes years.

So it certainly looks like we are heading for a critical mineral supply crunch.

As IEA Director Fatih Birol put it in their 2021 report ‘The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions’:

‘Today, the data shows a looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realizing those ambitions.’

Which countries are the largest producers of critical raw materials?

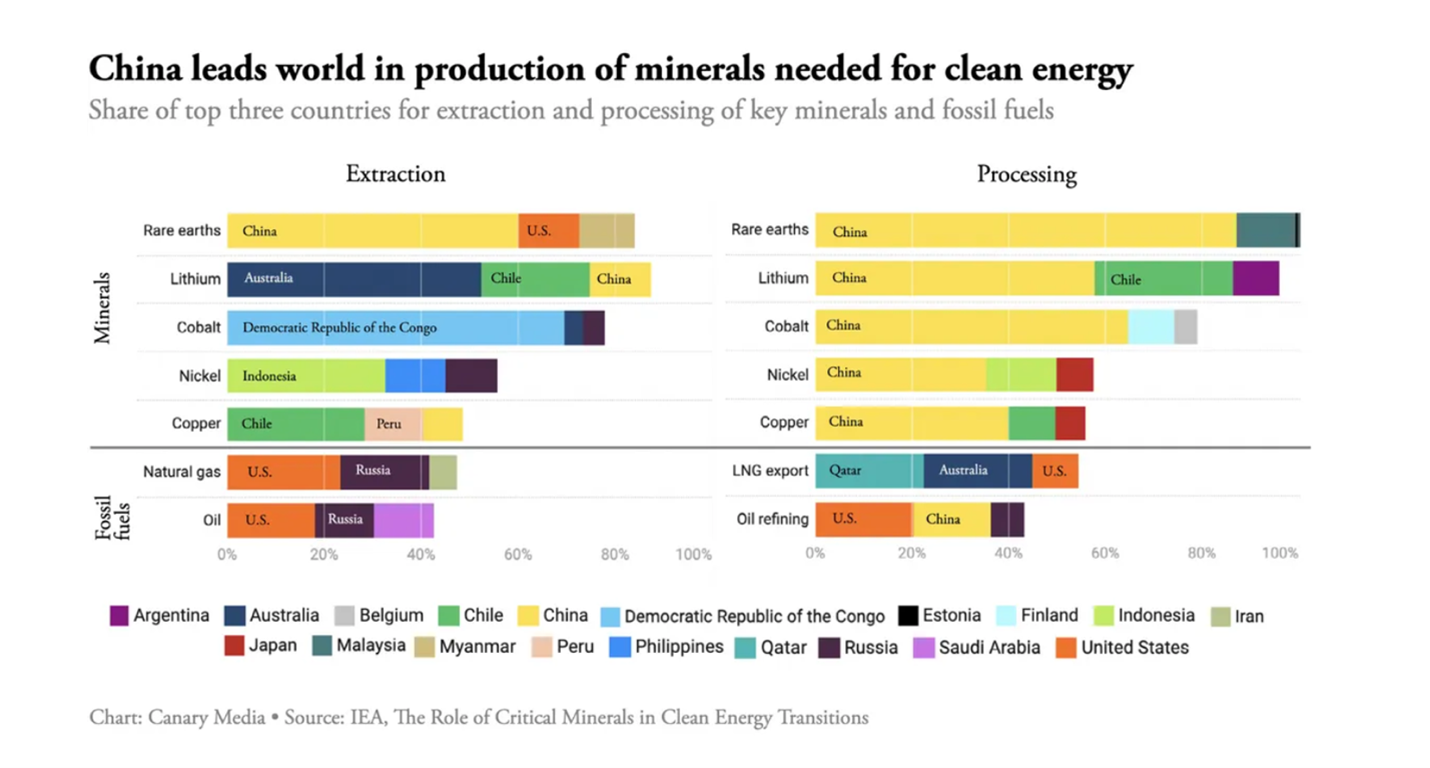

Australia is the world’s largest producer of lithium, with about 50% share of the global supply. Together with Chile, they hold close to 70% of the world’s lithium extraction.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has close to 70% of the global share of cobalt’s extraction, and together, Chile and Peru hold 40% of the world’s copper production.

In 2021, China produced just over 80% of the world’s graphite, Tungsten, and Bismuth. China’s also the top global producer of rare earths, with a 60% share.

But it’s not just about taking this stuff out of the ground. Raw materials also need to be refined before they can be used in things like batteries, China dominates here too.

China refines 40% of world’s copper, 60% of lithium, 73% of cobalt, and 85% of the world’s rare earths processing:

Source: Canary Media

What’s more, it produces many of the components needed for manufacturing batteries, controlling about 80% of the world’s lithium-ion manufacturing capacity.

In comparison, the US is a distant second, with a 6.2% share, and Europe with around 10% of the global battery manufacturing capacity in 2021.

That’s because China is the largest EV market in the world.

But it’s also a leader when it comes to renewable energy.

China produces more than 80% of the world’s solar photovoltaic panels, a number that could reach 95% by 2025 .

Governments are now racing to secure their positions in the critical mineral supply chain and reduce their dependency on China.

In 2022, for example, the US passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) pledging billions in energy security. What’s more, one of the main objectives of the IRA is to bring in more cleantech manufacturing into the US.

The IRA allocates around US$60 billion to ‘on-shore’ local manufacturing of things like solar panels, turbines, and transport tech. It’s also looking to accelerate EV uptake by offering tax credits to consumers.

But for the EV to qualify for these credits, there are some caveats.

The EV maker needs to finish assembling these vehicles in North America, and a percentage of the battery materials must be extracted or processed in the US…or a country the US has a free trade agreement with, like Australia.

So you can see how the IRA will be a catalyst for accelerating investment into the US’s EV supply chain and battery manufacturing…but it could also be a huge boom for Australia regarding supplying critical minerals.

In short, we’re not only going to need a massive number of critical minerals to supply the energy transition but also, with geopolitical tensions rising, there’s a race to build up non-Chinese critical minerals supply chains.

And this is at a time when supply for these critical minerals is already tight…

So Australia, as a supplier, could be very well placed to profit from this race to secure critical minerals.

How to invest in critical minerals

Most of these critical minerals don’t trade on public exchanges, which makes it difficult to invest in them directly.

The easiest way to invest in critical minerals is through an Exchange Traded Fund.

For example, the Global X Green Metal Miners ETF [ASX:GMTL] gives exposure to companies that produce critical metals for the energy transition. These include lithium, copper, nickel, and cobalt. The fund invests in global companies such as Albermarle, Gangfeng Lithium, Tianqui Lithium, and Allkem.

Also, the BetaShares Energy Transition Metals ETF [ASX:XMET] follows global producers of copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, manganese, silver, and rare earths.

Another approach is the Global X Battery Tech and Lithium ETF [ASX:ACDC], which follows a range of global companies involved in the lithium supply chain, from miners such as Pilbara Minerals to lithium-ion battery manufacturers like LG Energy.

Another way to invest in critical minerals is to invest in companies involved in the mining, processing, and refining of these minerals. Here, you can choose to invest in a range of companies that range from explorers to producers. Just note that investing in companies in the early stages can be risky.

You can look for companies that focus on one critical mineral. For example:

- Allkem [ASX:AKE] is a major lithium chemicals producer with assets in Australia, Argentina, and Canada. Allkem is also building the Nahara Lithium Hydroxide Plant in Japan that is expected to produce 10,000 tonnes per annum of battery grade lithium hydroxide.

- Pilbara Minerals [ASX:PLS] is also focused on lithium. It owns 100% of the Pilgangoora Project, located in Western Australia. Pilbara is also exploring becoming a fully integrated battery grade lithium hydroxide producer.

- Lynas Rare Earths [ASX:LYC] is the second largest producer of separated rare earths in the world and the only significant producer outside of China. Located in Western Australia, Mount Weld is one of the world’s highest-grade rare earths mines, according to the company. Once extracted, rare earth concentrate is sent to its processing plant in Malaysia for further processing. Lynas has a contract with the US Department of Defense to build a processing facility in Texas.

- Syrah Resources [ASX:SYR]: This Aussie miner aims to become a global supplier of graphite and active anode material. Syrah owns a 100% of Balama, a natural graphite resource in Mozambique, and is also building a processing site in Louisiana, US.

Or you can look at more diversified miners. For example:

- BHP Group [ASX:BHP] produces a range of materials including iron ore, copper, nickel, and potash. In fact, BHP’s Nickel West is one of the largest nickel producers in Australia. BHP also has a nickel sulphate plant in Kwinana, Western Australia.

- IGO [ASX:IGO] has several projects around Australia. This Aussie miner is focused on producing a range of clean energy metals including nickel, copper, and cobalt.

It’s also been busy building an integrated lithium business. IGO has a lithium joint venture with Tianqui lithium that has a stake in the Greenbushes lithium mine. The venture also holds an interest in the Kwinana Lithium hydroxide plant. Located in Western Australia, the plant is fully automated and the first lithium refinery outside of China.

Please be aware that none of the stocks mentioned here are official recommendations, they’re just ideas to get you started. We encourage you to conduct your own research.