If you’re late joining the uranium bandwagon, don’t worry; you’re not the only one!

Last week, I put together a detailed report on the uranium market, something that’s been a long time in the making.

It was part of our monthly recommendation to my paid membership group, Diggers and Drillers, in which we finally pulled the trigger on our first uranium position.

But has that come too late?

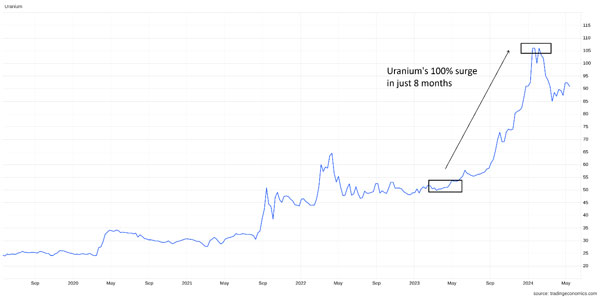

This commodity has already surged from just over US$50 per pound in April 2023 to more than US$100 per pound by January 2024.

| |

| Source: Trading Economics |

Since then, there has been a moderate pull-back; uranium is now consolidating just above US$90 per pound.

Can uranium rip higher from these

elevated levels?

Well, that depends.

Last year’s terrific run was driven by strong demand outlooks.

Uranium, the fuel for nuclear reactors, has benefitted from renewed interest in building global nuclear capacity. That’s partly due to the push to go green.

Here, nuclear power offers baseload power that’s carbon-free and reliable.

Whether night or day, cloudy or windless, nuclear provides uninterrupted power.

But there’s another important side to the nuclear story: costs are rising.

Despite central bankers’ claims to the contrary, inflationary pressures continue to loom.

Rising tariffs and trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies, China and the West, threaten to bifurcate global trade.

This is highly inflationary and occurs just as the West ramps up broad trade embargoes against Russia, one of the world’s most resource-rich nations.

Meanwhile, conflict could erupt at any time in the Middle East. A regional spillover could have drastic implications for global oil supply.

This 1970s setup could be good for uranium

I’m not the first to draw similarities between today’s inflationary environment and those from the 1970s.

Back then, the war in Vietnam helped drive copper prices to extreme levels, above US$15,000 per tonne. Meanwhile, OPEC oil embargoes in the early ’70s caused the price of oil to quadruple in the US.

As inflation rocketed higher, households sweated under a cost-of-living crisis. Governments were forced to find solutions.

This offered a fertile environment for the nuclear industry to expand.

As a source of relatively cheap baseload power, it offered a proven long-term solution to the global energy problem.

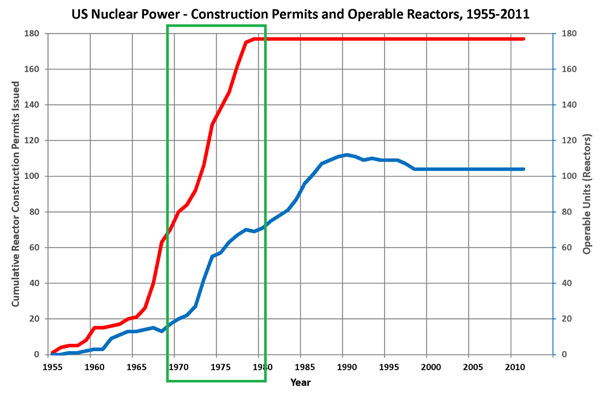

As you can see below, the US had fewer than 20 nuclear power facilities at the beginning of the 1970s. But by the decade’s end, the country had around 75 reactors in operation.

| |

| Source: Data from US EIA |

Undoubtedly, nuclear was viewed as a long-term strategy to tackle the 1970s cost-of-living crisis.

Not surprisingly, the commodity fuelling these reactors went skyward.

Adjusted for inflation, the price of uranium shot past US$200 per pound by the late 1970s. A record that stands today.

Today, uranium trades at less than half that price.

It begs the question…could we see another record high at some point in the 2020s?

If you believe the 1970s offers a blueprint for today’s economy, it’s certainly possible.

Inflationary pressures loom large against the backdrop of war, tariffs, embargoes and threats to energy security.

The political will to push nuclear expansion will only increase on the back of these drivers.

But what about the other side of the

uranium story…supply?

As the Canadian mining magnate Robert Friedland once stated, the set-up for higher commodity prices consists of one-third demand and two-thirds supply.

So, how does the uranium supply story stack up?

The outlook here is slightly less rosy for uranium investors.

Kazatomprom, the world’s largest uranium miner, is set to resume full production next year, removing production cuts adopted during uranium’s prolonged bear market following the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Meanwhile, the world’s second-largest miner, Cameco, is looking to ramp up its McArthur River operation in Canada. This will add a further 6.9kt of uranium to the global feedstock.

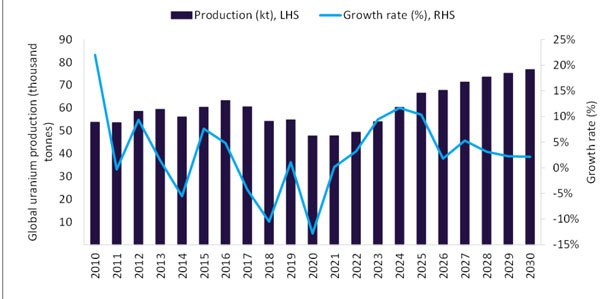

According to GlobalData, worldwide uranium production is expected to grow with a compound annual growth rate of 4.1% from 2024 to 2030, with output reaching 76.8kt by 2030.

| |

| Source: GlobalData |

So, what does that mean?

Rising output could defuse uranium’s long-term bullish outlook.

Plus, several other sources of new supply are set to hit the market in the coming years…

Paladin [ASX:PDN] is underway with restarting its Langer Heinrich uranium mine in Namibia.

The mine is expected to deliver 6 million pounds annually at full production, enough to supply over ten 1,000 megawatt nuclear power plants for a year.

Then there’s South Australia’s Honeymoon operation.

This was Australia’s second operating in-situ recovery uranium mine…the timing was unfortunate; production started alongside the infamous Fukushima disaster in 2011.

Operations at Honeymoon were suspended in 2013 due to falling uranium prices.

In 2015, Boss Energy [ASX:BOE] acquired the project and finally recommissioned the mine with production resuming earlier this year.

Then there’s the Kayelekera Uranium Project in Malawi. Its new owners, Lotus Resources [ASX:LOT], also plan to bring the mine out of care and maintenance.

So why is this a potential threat to the uranium market?

Fully permitted mines with infrastructure already in place means several operations could come online simultaneously, easing any potential supply squeeze driven by demand.

So, should you be getting into this market?

For now, investors remain laser-focused on the demand outlook. That means there’s still plenty of room to ride momentum in the uranium market.

In the long term, though, demand must overcome higher production threats.

A 1970s-like cost-of-living crisis could be exactly the type of high demand scenario bringing more reactors online and more demand for this commodity.

But uranium won’t be the only winner in this scenario…oil and gas stocks could emerge from the ashes amid rising energy costs.

This is another energy sector that’s worth watching closely.

Especially while energy markets remain in a temporary lull.

We’ll have much more to say about that next week.

Until then.

Regards,

|

James Cooper,

Editor, Mining: Phase One and Diggers and Drillers

Comments