I have a confession to make.

Whenever I hear of Australia’s record of close to 30 years of economic growth, I think of how much risk that brings. Recessions are a way for the system to cleanse itself, not having one for so long could make the next one much worse.

But then, I also get a small twinge of envy.

Not having a recession for this long has allowed people to accumulate a lot of money, as things have pretty much stayed the same. Recessions usually bring along change.

Don’t get me wrong, economic crises and recessions can be great money-making opportunities…if you are ready for them. If you are not, they can mean a wealth wipe out.

I’ve lived through a few of these potentially life-changing moments already.

In 1989, Argentina had a massive battle against hyperinflation, with the inflation rate hitting a whopping 3,000% for the year. If you’ve ever experienced hyperinflation, you know it breeds instability, fear, and depression.

I remember prices going up hourly, going for a coffee in the morning and having to pay more for that same coffee in the afternoon. As soon as people got their salaries at the start of the month, there was a massive rush to the bank to exchange it into US dollars to keep the value of that money.

On the other hand, hyperinflation made any debt you were holding cheaper…as long as you weren’t holding debt in foreign currency.

Then in 2001, I was a couple of years into my first job in Boston (US) when the dotcom bubble popped. I remember many of my friends from Uni losing their high-paying tech jobs. I remember my boss having to defer her early retirement plans after her pension savings took a massive hit.

** Market expert Shae Russell predicts five knock-on effects of the recent market crash that could be even bigger threats to the average investor’s wealth than the crash itself. Learn more here. **

She wasn’t the only one.

By the end of 2002, 70% of people had lost at least 20% of the value of their 401ks.

And then, I was living in Spain in 2003 in time to see an impressive property boom…and an even more spectacular property collapse in 2008.

I remember the thousands of ‘for sale’ signs in the windows and semi-finished abandoned estates.

People were left with properties worth less than what they owed on their mortgages. Unemployment spiked. So many people looking for jobs pushed down salaries. The euro got you further than before and anyone with cash could pick up bargains.

All of these were quite different from each other, in how they came about and what they brought in the aftermath.

In the 1989 crisis the government printed lots of money, which brought about inflation. There was a lot of money around and that money kept losing its value.

In 2008, in contrast, high unemployment and debt caused people to stop spending and pay off debt. Money disappeared from the system and debt became a burden. It brought deflation.

Now we are facing a pandemic that has stopped the world.

The aftermath of the Coronavirus…

Will the aftermath bring inflation or deflation? A or B? It’s the big question every economist is trying to answer.

On one hand, the economy is stopped and demand has collapsed. People are losing their jobs, staying at home, saving more, and spending less.

So far, it’s looking deflationary.

But then, what’s interesting about this crisis is that supply chains are breaking down as COVID affects them. We are not able to get certain things at certain times, which could create inflation.

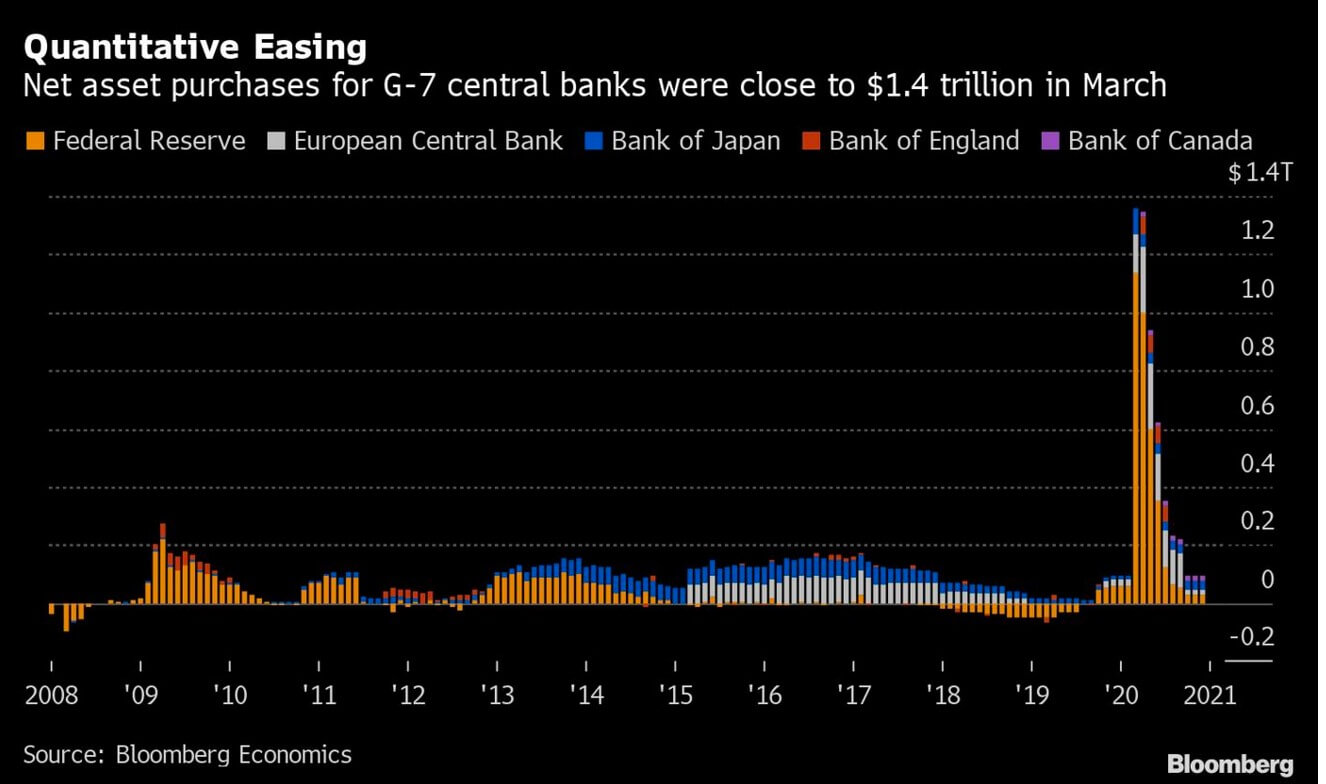

We also have central banks flooding the system with lots of money. And I mean lots, more than in 2008, as you can see below.

|

|

|

Source: Bloomberg |

As Bloomberg reports, G7 central banks purchased almost US$1.4 trillion in March, five times more than the peak of US$270 billion in April 2009. And that’s only in March.

In 2008, all this ‘money printing’ by central banks didn’t really create inflation. Anytime the government prints money we get inflation, it’s a rule I learned from the 1989 hyperinflation event. But it didn’t this time. It’s something that’s baffled me for some time.

With quantitative easing, money doesn’t flow directly to people creating inflation in consumer prices. Instead, it inflates stock prices and properties.

For Australia, the difference this time too, is that while we pretty much avoided the 2008 crisis, this time the central bank has already started a quantitative easing program.

This isn’t a question of A or B

We are wondering if all this will be inflationary or deflationary.

I don’t think this is a question of A or B.

I think it’s a C answer.

The fundamental point I think you should be thinking about here is that the money flowing through the economy is not coming from what the economy is producing, but from central bank money printing.

There is something very wrong when the economy has pretty much stopped, but the stock market is still rising.

The system is completely broken and COVID-19 is exposing this.

It’s why it’s a good idea to hold some cash, and gold.

|

Best, |

|

|

Selva Freigedo, |

PS: In a brand-new report titled ‘The Looming Aussie Recession and How to Survive It’, Nick Hubble reveals why a recession in Australia is inevitable and three steps to recession-proof your wealth. Click here to receive your free report.