News of the US Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapse has flooded the media headlines over the past week, and unsurprisingly, many are wondering how it fits in with the real estate cycle.

First the backdrop.

For those not aware, SVB was a leading provider of financial services to technology and innovation start up industries.

The bank is headquartered in Santa Clara, California, but operates in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

SVB worked with many well-known companies and investors, including Apple, Google, and Amazon — as well as venture capital firms like Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital.

Before the collapse, it was the 16th largest bank in the US, with more than $200 billion in assets.

And while I don’t expect the collapse to disrupt our run into the peak of this cycle, it is significant — for reasons I’ll explain below.

It’s the single largest US financial institution to fail since the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers during the global financial crisis.

Additionally, it comes almost 15 years to the day, 16 March 2008, since the investment bank Bear Stearns collapsed during the subprime mortgage crisis.

What happened? How did we get here?

Well, as you may have read, SVB’s customers were start-ups and other tech-centric companies.

Rising costs and accrued losses increased the need for cash over the past year, leading many to progressively drawdown on their deposits.

(Note: Tech companies do not perform as strongly in the second half of the cycle as they do in the first half.)

Panic started last week when Silicon Valley Bank announced that it had sold a bunch of securities at a loss and would sell another $2.25 billion in shares to shore up finances.

Investors concluded that if the bank had enough money to cover everyone’s deposits, why would they need to raise more money?

The thing is, SVB held billions of dollars’ worth of government bonds on its books — including those backed by mortgages (mortgage-backed securities).

This is common for most banks.

Banks are, for all intents and purposes, safe as houses (so to speak).

But bonds have an inverse relationship with interest rates — when rates rise, bond prices fall.

So, when the Fed started its fastest rate-hiking cycle in history, foolishly thinking it would combat inflation (a myth I discussed with renegade economist Steven Keen the other week), SVB’s bond portfolio lost much of its value (as did many other banks).

After all, over the last 18 months, we’ve witnessed the largest-ever markdown in treasury pricing.

This is not generally visible at a glance, as bonds are assumed to be a long-term investment, and banks are not required to book declining values until they are sold.

That means, through a bit of clever accounting, their value never changes on the books — even though it does in reality.

But by December last year, SVB had lost a whopping $23 billion on their $57 billion government bond portfolio, leading to their credit status being downgraded.

Ultimately, it caused a run on the bank, with depositors racing to digitally pull their funds out.

To cut a long story short, SVB could not keep up with the withdrawals, and the whole thing went belly up.

Their stock price tanked more than 60% in one day, and then another 20% after hours.

By Friday the stock was halted, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) took over the bank.

The FDIC insures deposits up to $250,000. But according to reports, only 2.7% of all total deposits were under this amount.

(Note: this is quite a unique situation. Apparently, among the top 100 largest banks in the US, only one other bank has a smaller share.)

Federal regulators stepped in on Sunday to back all SVB deposits, hours before stock markets resumed trading — as well as at New York’s Signature Bank, which was also seized on Sunday.

Of course, they had no choice…allowing depositors to lose money would spark a run on smaller/regional banks and lead to more concentration of banking power.

It could also lead to a very sharp economic contraction/job losses and general chaos.

As a response, late Sunday the Federal Reserve launched an extensive emergency lending initiative with the aim of reinforcing trust in the country’s financial system.

Biden fronted the cameras yesterday to stress that he would seek stronger regulations for banks and that Americans can be ‘confident in the financial system’…

So, what now?

Unlike in 2008 — when the timing was prime for the end of the cycle — this is not going to trigger a broader collapse.

We’re not there yet.

Firstly, the policy response should settle markets and prevent wider contagion.

Additionally and importantly, the bank didn’t fail because of bad loans against real estate, as we would expect to see at the end of the real estate cycle when there is a serious recession/depression looming.

Rather, it failed due to due to poor risk management.

Therefore, we would not expect SVB’s issues to have a widespread impact on other US banks.

We’re not looking at multiple bank collapses from risky lending practices related to housing that caused the global financial crisis (GFC).

While the problems faced by SVB may be concerning for the bank and its customers, they are not indicative of larger issues within the banking sector as a whole.

It’s worth noting that the GFC was caused by a combination of factors, including the widespread issuance of subprime mortgages and the securitisation of those mortgages into complex financial products — leveraged against speculation on rising land values.

Hence why the IMF concluded a few years ago post the GFC:

‘…our research indicates that boom-bust patterns in house prices preceded more than two-thirds of the recent 50 systemic banking crises…’

IMF ‘Era of Benign Neglect of House Price Booms is Over’

11 June, 2014

No kidding.

As you’re aware, the resulting housing market collapse significantly impacted the broader financial system and economy.

In contrast, SVB’s issues are isolated. It will not have a similar impact on the financial system.

While any bank failure or financial disruption is cause for concern, it’s important to keep these issues in perspective within the context of the real estate cycle.

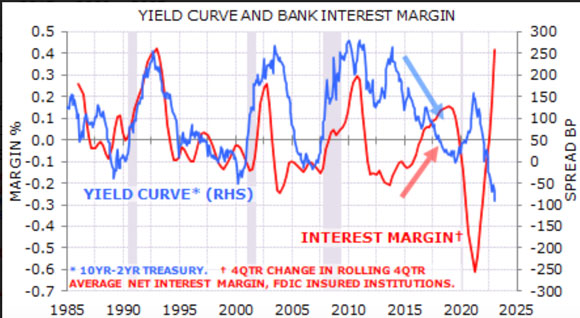

It’s also important to note that margins in the banking sector are very healthy.

Major banks are cashed up and pulling in record profits — higher interest rates being advantageous in this respect.

Take a look at the chart below from Gerard Minack:

|

|

| Source: Gerard Minack |

‘It used to be as banks funded-short/lent-long that margins suffered as the yield curve flattened. But now that most banks have a large exposure to floating-rate assets — including a massive stock of interest-paying bank reserves — rising rates are great for profits. Net interest margins are rising as the curve has been flattening’

Gerard Minack

Rapid cash rate hikes obviously pose risks of further shocks to the system as financial conditions continue to tighten.

However, in response to the collapse, it could be that we’ll see an adjustment to monetary policy.

No doubt the banking industry will be putting lots of pressure on the Fed to lower rates and steepen the yield curve.

Additionally, we’re also potentially looking at changes to banking regulations that could assist in creating more credit for real estate speculation as we transit into the ‘winner’s curse’ phase of the cycle over the next few years…

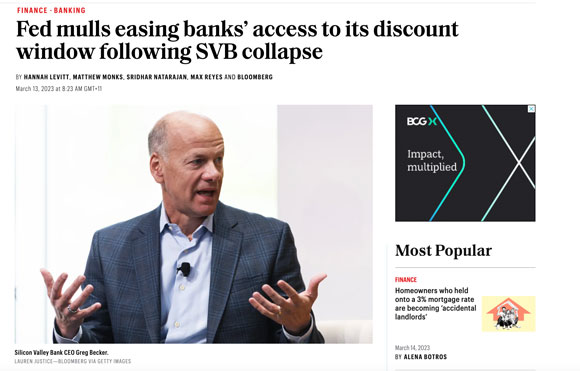

|

|

| Source: Fortune |

‘The Federal Reserve is considering easing the terms of banks’ access to its discount window, giving firms a way to turn assets that have lost value into cash without the kind of losses that toppled SVB Financial Group.’

Bloomberg

The cycle is by no means at an end yet.

There’s still more upside to go, and we’re already seeing the seeds and drivers of it in the Australian market.

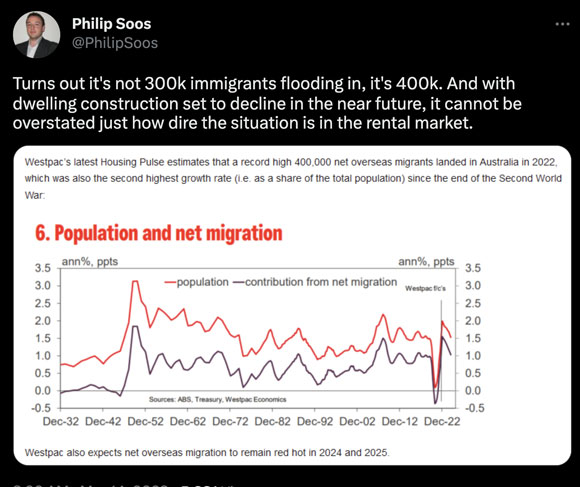

Immigration is rocketing up against acute shortages in supply in both the sale and rental markets.

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

Buyer incentive — a swing from stamp duty to land tax in NSW, for example — is also assisting in buffering the impact of rising rates on falls to median values.

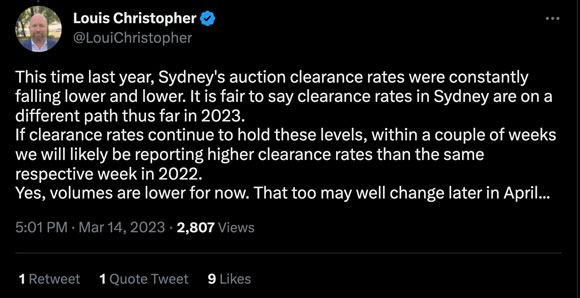

Increases in the clearance rate in Sydney (should the trend continue) will inevitably bring rises in the median when coupled with increased market confidence.

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

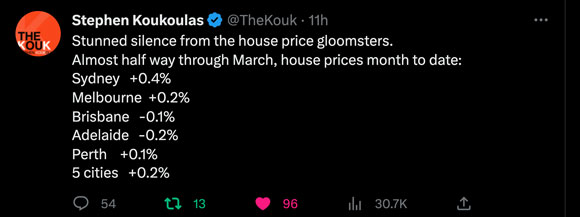

We’re already seeing the effects…

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

I’ll give the final comment to my friend, economist Philip Soos, who has provided subscribers of Cycles, Trends & Forecasts with excellent analysis over the last few years regarding the direction of real estate values, state-by-state, with the use of his CAPE (cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio) charts.

This allowed us to accurately call the bullish market turns that occurred between 2020 and 2022 in all capitals prior to the COVID-panic — as well as the following downturn in Sydney and Melbourne post the 2021 early 2022 peak.

Over to Philip.

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

As I said, we’re not there yet.

Sincerely,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor

Comments