If you’re reading this article from a mobile device or computer, you’re benefiting from the use of rare earth metals.

Rare earth metals are used almost everywhere, and they’re indispensable for modern society.

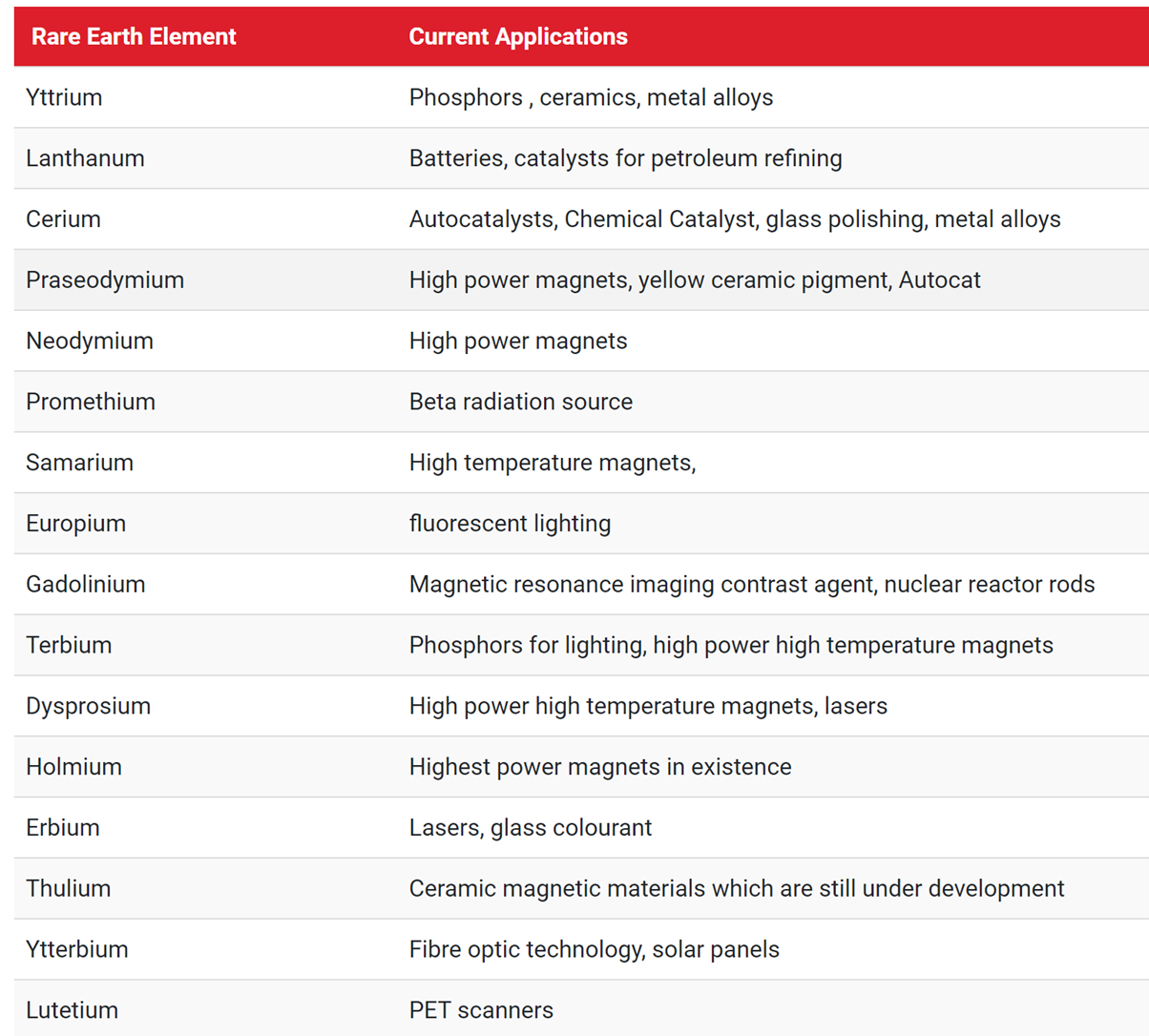

The global demand for rare earth metals doubled to 125,000 tonnes in 15 years and the demand is projected to reach 315,000 tonnes in 2030.

The demand is accelerating due to the growing popularity of green technologies and more sophisticated electronics.

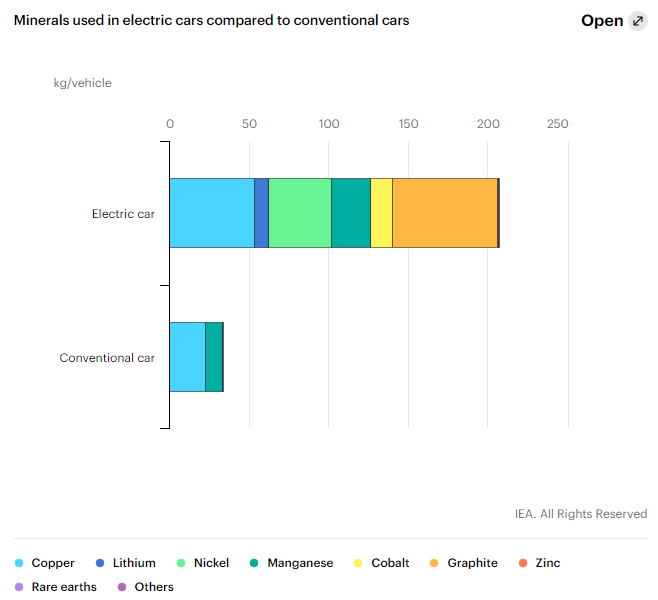

A great illustration of why a shift to greener tech is lifting demand for rare earths is captured below in a neat chart from the International Energy Agency:

Source: IEA

As you can see, the electric car — a pillar of the world’s green future — requires substantially more minerals…including rare earth minerals.

It’s no surprise, then, that plenty of investors are excited about the profit potential of rare earth stocks.

But should you invest in rare earth stocks?

I know you’re looking for a straight answer to this. But you have to understand that investing, in general, is a complex topic that has to be analysed from multiple angles and investing in rare earth stocks is no exception.

In this article, I’ll walk you through everything you need to know about rare earth metals and rare earth stocks. That way, you can decide for yourself whether or not they’re a good investment.

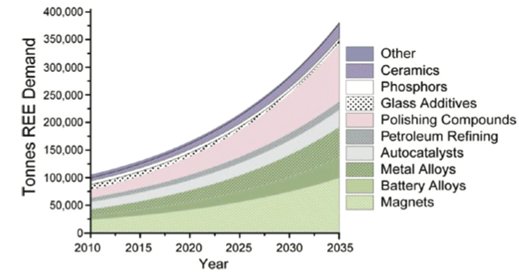

Source: MIT

What are rare earth minerals?

Rare earth minerals (also called rare earth metals) are a group of chemically similar, metallic elements with atomic numbers 57 to 71.

In order, these elements are lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), praseodymium (Pr), neodymium (Nd), promethium (Pm), samarium (Sm), europium (Eu), gadolinium (Gd), terbium (Tb), dysprosium (Dy), holmium (Ho), erbium (Er), thulium (Tm), ytterbium (Yb) and lutetium (Lu).

Together, these minerals make up the lanthanide series and can be further divided into light rare earths (lanthanum–gadolinium) and heavy rare earths (terbium–lutetium).

Now, scandium (Sc, atomic number 21), yttrium (Y, atomic number 39) and thorium (Th, atomic number 90) can also be classed as rare earth minerals because of their similar chemical properties.

[openx slug=postx]

Source: Reuters

Where are rare earth minerals used?

It is almost impossible to avoid a piece of technology that does not contain a rare earth element.

While the names of the constituent rare earth elements seem arcane, they are the silent and out-of-the way enablers of our modern, tech-savvy lifestyles.

For instance, ubiquitous devices like mobiles, TVs, and computers all contain rare earths.

Electronics is one of the largest applications for rare earth minerals. Without rare earth minerals, our electronic devices may not function as well and be considerably bulkier and heavier.

Rare earth minerals are also widely used in the making of cars, with vehicle manufacturing one of the biggest consumers of rare earths.

Rare earths also power the green revolution.

REEs are an important component for EV motors and wind turbines.

The International Energy Agency estimates that clean energy technologies make up over 40% of demand for rare earth minerals.

Source: Lynas Rare Earths

Are rare earth minerals actually rare?

Contrary to the name, rare earths are not very rare at all. You could consider rare earths a misnomer.

At the time of their discovery in the 18th century, rare earths were considered scarce and were therefore described as rare.

But REEs are quite abundant, scattered across many of the globe’s workable deposits.

While abundant, the concentration levels of rare earths in many ores are quite low (less than 5% by weight).

An economically viable source of REEs should contain more than 5% rare earths, unless they are mined along with another product like iron or uranium.

The process of extracting and processing REEs can also be complicated and costly.

This is because the chemical properties of rare earth minerals make them difficult to separate from surrounding materials or even from one another.

As the Scientific American explained:

‘Extraction is complicated by the fact that in the ground, such elements are jumbled together with many other minerals in different concentrations.

‘The raw ores go through a first round of processing to produce concentrates, which head to another facility where high-purity rare earth elements are isolated. Such facilities perform complex chemical processes that most commonly involve a procedure called solvent extraction, in which the dissolved materials go through hundreds of liquid-containing chambers that separate individual elements or compounds—steps that may be repeated hundreds or even thousands of times.

‘Once purified, they can be processed into oxides, phosphors, metals, alloys and magnets that take advantage of these elements’ unique magnetic, luminescent or electrochemical properties. The strong and lightweight nature of rare earth magnets, metals and alloys have made them especially valuable in high-tech products.’

Current REEs production also uses lots of ore, generating plenty of harmful waste to extract small quantities of rare earth minerals.

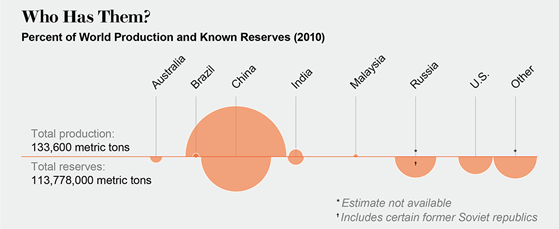

Which are the biggest rare earth minerals producers?

China is the biggest producer of rare earth minerals. Other prominent rare earths producers are Brazil, India, Russia, South Africa, Malaysia, and the US.

According to the US Geological Survey, China made up 63% of global rare earths production in 2019.

This can rise to 80% if you include China’s undocumented production activity.

Since the mid-1990s, China has dominated the global supply of rare earths.

Most of China’s production derives from the Bayan Obo iron–niobium–rare earth elements deposit in Inner Mongolia, China.

China’s rare earth production exceeds the world’s second-largest producer — the US — by more than 100,000 tonnes.

Despite the US being the second-largest producer, it still imports REEs from China to make up local demand. In 2021, 80% of the US’s REEs imports came from China.

Source: Scientific American

Apart from being the main rare earths miner, China also holds at least 85% of the world’s capacity to process rare earth ores into usable material.

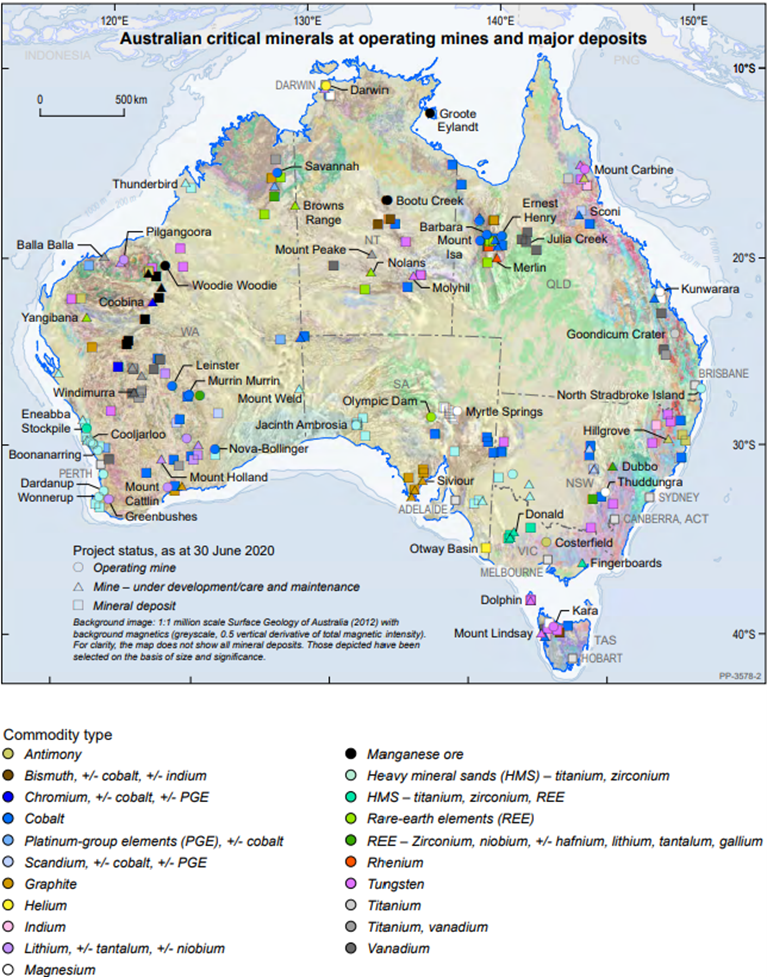

Regarding Australia, here’s a nice map below outlining the critical mineral deposits and major mines in the country:

Source: Geoscience Australia

History of rare earth mineral production

Rare earths were discovered in Sweden in 1787 when one Karl Arrhenius collected a black mineral we now reference as ytterbite. The mineral was found near the village of Ytterby, hence the name.

But it was not until 1794 that an impure yttrium oxide was isolated from the mineral ytterbite by a Finnish chemist Johan Gadolin.

Development was slow — again evincing the complicated nature of separating rare earths from other materials — and it wasn’t until the 1880s that REEs were produced commercially.

Rare earth metals in pure form were first prepared in 1931 but significant uses were not developed until the late 1960s.

The use of individual rare earth metals rose along with the efficiency of the technology to separate it.

Mirroring what happened to improved lithium battery technology, demand for rare earth minerals shot up as efficiencies and technological breakthroughs led to lower prices.

As the US Geological Survey reported, prices of commercial quantities of rare earth minerals fell considerably as availability and extraction technology rose.

Source: Australian Rare Earths

Why don’t other countries produce rare earth metals?

If the rare earth metals are in high demand and every country needs them, then why don’t they produce their own?

The answer harkens back to classical economists like David Ricardo and Adam Smith — comparative advantage.

For some countries less endowed with fertile rare earths reserves, it’s more efficient to import than produce.

While self-reliance is nice, it is also costly. Globalisation and international trade minimise these costs.

If countries don’t have rare earths reserves of large enough size or high enough grade, it will be uneconomical to mine and extract.

How much do rare earth minerals cost?

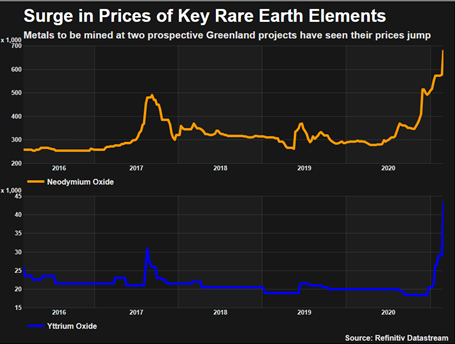

The global demand for rare earth minerals is rising as the world manufactures more products requiring rare earth minerals as inputs.

Source: Reuters

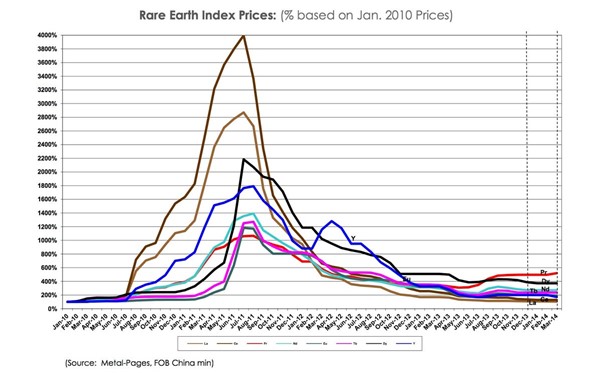

For instance, the price of rare earth praseodymium — commonly used in magnets for EVs, smartphones, and military equipment — more than doubled over 14 months to October 2021, selling for about US$102/kg.

But there’s an interesting comparison to praseodymium’s price peak that illustrates the swing producer power of China.

Praseodymium reached a high of about US$250/kg in August 2011 when China threatened to clamp down on exports.

As long as China retains its production hegemony over rare earths — and no substitutes for the minerals are found — the price of rare earth metals will be closely tied to China.

China is known to use quotas to preserve the strategic minerals to prevent domestic shortages, which can exacerbate supply tightness.

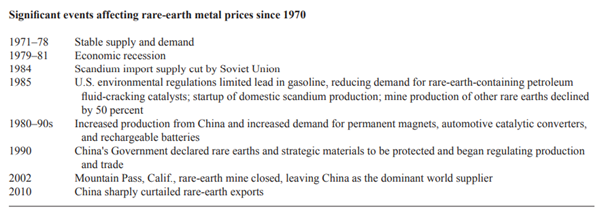

A great historical overview of factors affecting rare earths prices is neatly captured below, taken from the US Geological Survey organisation:

Source: US Geological Survey

[openx slug=postx]

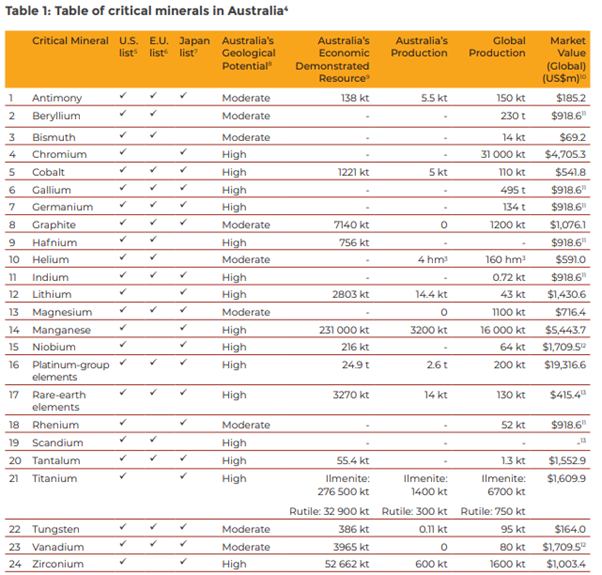

Are rare earth metals considered critical minerals?

In recent years, rare earth minerals were characterised as critical elements in the EU countries and by the Australian and US governments.

This means rare earth minerals are designated as strategically and geopolitically important.

For instance, the US government categorises rare earth minerals as critical to the US’s economic and national security.

Revealingly, the Trump administration exempted rare earth elements from tariffs it imposed on US$300 billion worth of Chinese imports.

Geopolitics plays a big part in elevating rare earths in importance.

Tensions between superpowers tend to spotlight heretofore unremarked issues — like access to resources such as rare earth minerals.

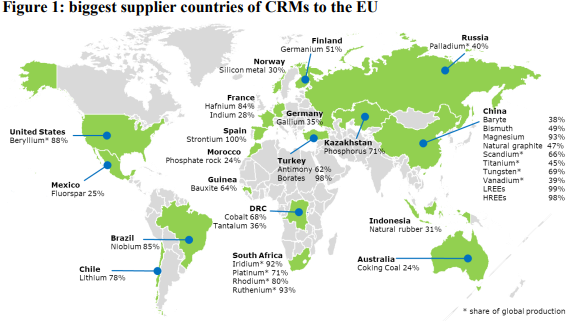

Take the European Union.

China provided 98% of the EU’s supply of rare earth elements in 2020.

This dependence would not sit well with the European Union. Such comprehensive dependence dilutes political leverage.

In the geopolitical sphere, lack of resource self-sufficiency is akin to playing with a weak hand.

Just consider what the 2020 EU Commission Report on critical raw materials resilience said:

‘Gaps in EU capacity for extraction, processing, recycling, refining and separation capacities (e.g. for lithium or rare earths) reflect a lack of resilience and a high dependency on supply from other parts of the world. Certain materials mined in Europe currently have to leave Europe for processing. The technologies, capabilities and skills in refining and metallurgy are a crucial link in the value chain.

‘These gaps, and vulnerabilities in existing raw materials supply chains, affect all industrial ecosystems and therefore require a more strategic approach: adequate inventories to prevent unexpected disruption to manufacturing processes; alternative sources of supply in case of disruption, closer partnerships between critical raw material actors and downstream user sectors, attracting investment to strategic developments.’

Source: European Commission report

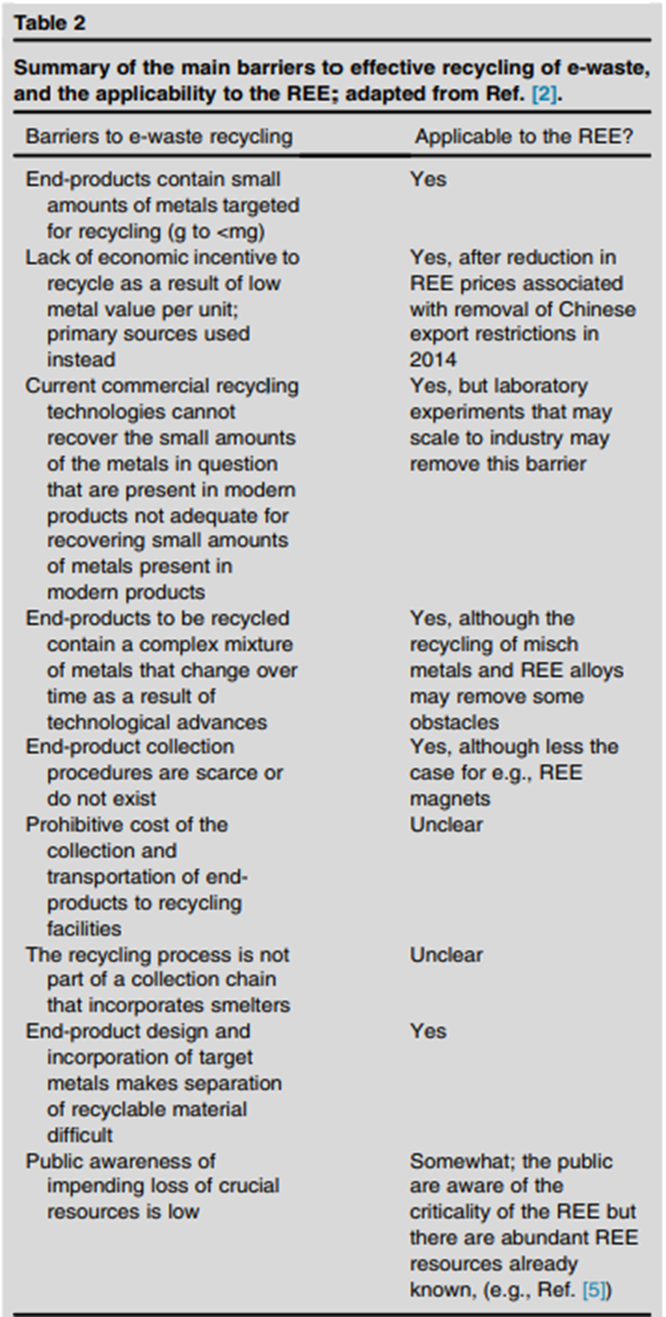

Can rare earth minerals be recycled?

Rare earth metals are found in countless electronic devices, wind turbines, car parts, and equipment.

If demand for REEs is only set to rise, then recycling items containing REEs could become an important contributor to supply stability.

Currently, however, recycling rare earths isn’t a significant contributor to supply.

As a 2018 research paper estimated, only about 1% of REEs are recycled from end-products. The rest is confined to waste, removed permanently from the materials cycle.

Source: Jowitt et al

Recycling is a partial answer to many finite resource problems, but recycling rare earths is not as easy as recycling glass or plastic.

Although many used electronics contain rare earth metals, the amounts contained are very small.

This means the process of recovering them is usually more expensive and costs can be prohibitive.

For instance, many recycling plants focused on REEs stopped operations due to decreasing prices of rare earths following the 2011 peak.

As prices rise again, however, recycling — and margins — become more attractive.

Source: Cewaste

As the International Energy Agency’s report on critical minerals states:

‘[A] strong focus on recycling, supply chain resilience and sustainability will be essential.’

Rare earth mineral recycling will grow in importance and prominence as technology improves the efficiency and environmental impact of current practices.

For instance, rare earth metals can now be recovered from mobiles, laptops, and EVs via hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical processes.

But both have environmental drawbacks that don’t align with the green ambitions rare earths serve.

As rare earths researcher Cristina Pozo-Gonzalo wrote in 2021:

‘Pyrometallurgy is energy-intensive, involving multiple stages that require high working temperatures, around 1,000℃. It also emits pollutants such as carbon dioxide, dioxins and furans into the atmosphere.

‘Meanwhile, hydrometallurgy generates large volumes of corrosive waste, such as highly alkaline or acidic substances like sodium hydroxide or sulfuric acid.’

Widespread recycling of REEs at scale is still firmly in the future. But the critical importance of these minerals is awakening private enterprise and government alike.

As a 2018 research paper led by Simon Jowitt concluded:

‘The REE are among the most critical of the critical elements yet current efforts to recycle these valuable commodities are seemingly relatively ineffective.

‘There is significant potential to increase the amount of the REE recycled from major end-uses, such as permanent magnets, fluorescent lamps, batteries, and catalysts; however, a significant amount of research is needed in all of these areas to increase the amount of these elements.

‘Increased amounts of REE recycling has the potential to play a key role in addressing a number of criticality issues with these elements, including meeting increased demand, increasing their security of supply, and overcoming the balance problem between higher and lower demand REE and the concentrations of the REE available from primary mine-derived sources.’

What are rare earth stocks?

If someone decides to invest in rare earth minerals, they can’t buy the metal directly like they can with gold.

Often, the best way to gain exposure to rare earth is via listed companies involved in mining, extracting, and processing the minerals.

Here’s a selection of ASX rare earths stocks.

Note, these are in no way recommendations. We list them here for you to kickstart your own research.

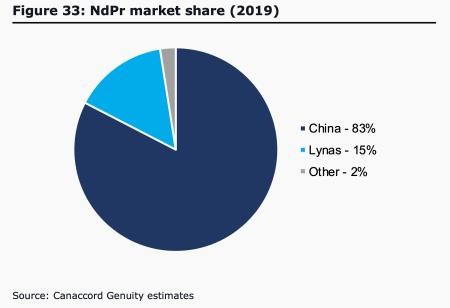

Lynas Rare Earths Ltd [ASX:LYC]

Lynas is one of the world’s few significant rare earths producers outside China and the biggest rare earths miner in Australia.

Lynas is an Australian company that operates the Mount Weld mine in Western Australia. LYC describes the Mt Weld mine as one of the highest-grade rare earth mines in the world.

This rare earths stock is the world’s second largest producer of REEs neodymium and praseodymium — two light rare earths.

Together, the two metals are present in iPhone magnets.

Source: QZ

Lynas also operates the world’s largest single rare earths processing plant in Malaysia.

LYC’s price chart below shows the cyclical nature of resources stocks — the stark peaks and troughs informed by changes to the demand and supply equation.

LYC shares soared to an all-time high in 2011 amid Chinese rare earths restrictions. But the Lynas stock plunged after the rare earths bubble burst late in 2011.

LYC shares plunged below a dollar before a slow recovery as shift to green tech and rising geopolitical tensions raised the global importance of rare earths.

Source: Tradingview.com

Australian Strategic Materials Ltd [ASX:ASM]

Lynas is not the only company wishing to sell itself as an alternative to China’s rare earths hegemony.

ASM is a junior integrated producer of critical metals for advanced and clean technologies.

Its Dubbo Project in central New South Wales has reserves of rare earths, zirconium, niobium, and hafnium.

Like Lynas, ASM aims to position itself as one of the few REE supply options outside China.

In 2021, a consortium of South Korean private equity firms pledged to invest $340 million in Dubbo rare earths project in return for a 20% stake.

The deal also included a 10-year metal offtake agreement with a metals plant being built by ASM in South Korea.

Source: Tradingview.com

Northern Minerals Ltd [ASX:NTU]

Northern Minerals is a junior Australian rare earths stock.

Taking a different tack to its peers, NTU wishes to specialise in ethically produced rare earths, with the ambition of becoming a principal supplier of ethically produced REEs.

NTU has a large landholding in Western Australia and the Northern Territory it is prospecting for viable rare earths.

Northern Minerals’s current portfolio comprises three projects: the Browns Range and John Galt projects in WA, and the Boulder Ridge Project located in the NT.

NTU’s flagship project is the 100%-owned Browns Range Project, which hosts a pilot plant testing several deposits containing dysprosium and other heavy rare earths.

Source: Tradingview.com

Vital Metals Ltd [ASX:VML]

Vital Metals is an explorer focusing on prospective mineral projects in Canada and Africa.

In 2021, VML started rare earths production at the Nechalacho Project in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

This makes VML the first rare earths producer in Canada and only the second in North America.

Vital Metals describes the Nechalacho project as possessing some of the highest-grade rare earth deposits in the world.

VML expects to produce 5,000 tonnes of rare earth oxides by 2025, and it has plans to open a new rare earth metals project in Tanzania

Source: Tradingview.com

Arafura Resources Ltd [ASX:ARU]

Arafura Resources is an Australian company currently developing the Nolans Project in the Northern Territory.

ARU aims to have the Nolans Project encompass both mining and processing.

Nolans contains a rare earths-phosphate-uranium-thorium (REE-P-U-Th) deposit, which it describes as one of the largest and most intensively explored deposits of its kind in the world.

ARU aims for Nolans to supply 5–10% of total global demand for neodymium and praseodymium.

Arafura will focus on securing project finance in 2022 to construct and operate the Nolans project as well as secure offtake agreements before making a final investment decision.

ARU is targeting first production in late 2024, with the project expected to cost more than $1 billion in capital costs

Source: Tradingview.com

Hastings Technology Metals Ltd [ASX:HAS]

Hastings Technology is an Australian exploration and development company.

HAS is developing two rare earth metals projects in Western Australia — the Brockman Project and the Yangibana Project.

Hastings aims to produce magnet rare earths, primarily neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium.

In 2021, HAS received commendation from Western Australia Premier Mark McGowan for its work to develop the Yangibana project.

In Premier McGowan’s view, the project aligns with Western Australia’s Future Battery Industry Strategy, which aims to expand the range of future battery minerals extracted and processed in WA.

Source: Tradingview.com

Rare earth stocks risks and opportunities

The opportunity — rising demand

We can infer the rising importance of rare earths by the way countries think about them.

The European Union, for example, has classified rare earths as critical elements.

The EU has declared it wishes to build up its resilience in the rare earths value chain, a strategic aim it deemed ‘vital to most EU industrial ecosystems (including renewable energy, defence and space).’

Given China’s dominant current position in the global production of rare earths, we can expect the US to pour plenty of resources building its rare earths resilience.

As long as a superpower like China controls key materials like rare earths, other superpowers will try to wean themselves off and shrug off the dependence.

But it’s not just geopolitics that are favourable to rare earths demand. REEs technological applications are driving up the price, too.

The EU estimates, for example, that demand for REEs used in permanent magnets for EVs, digital technologies, and wind generators could increase 10-fold by 2050.

According to Fundamental Research Corp, each electric vehicle requires roughly 10kg of rare earth elements. Wind turbines use up to 408kg.

As another example, S&P Global reported that the price of praseodymium neodymium — a rare earth mineral used in electronic equipment — doubled in a year to hit US$117,300/mt in August 2021.

The rising demand for rare earth metals follows a wider trend.

Demand for raw materials as a whole is rising in line with population growth, industrialisation, decarbonisation, and adoption of new technology.

If countries wish to break their reliance on China’s rare earths, they will have to turn to companies operating and prospecting outside China…companies in Australia, for instance.

The following excerpt from a 2021 piece in The Australian nicely summarises the strategic opportunities for ex-China rare earths providers:

‘Major Korean manufacturers such as Hyundai, Samsung, LG, POSCO and others know that their future partly rests in the electric vehicle, battery power and renewable energy revolution. They also know that China is eyeing the same prize, in both domestic and in export markets – and that history shows that Chinese companies will get preferential treatment when it comes to supply from the country’s dominant position in rare earth metals production.’

Source: Department of Industry

Rare earth stock investing risks

Investing in resource stocks incurs plenty of risks. Investing in rare earths stocks is no different. Being aware of the risks is vital. So here are some of the most noteworthy:

1. China’s status as a swing producer

As we covered earlier, China makes up the vast bulk of the world’s rare earths production…and processing.

For instance, the EU relied on China for 98% of its rare earths stock in 2020. Most countries are in a similar boat.

We can therefore describe China as a swing producer of rare earths. A swing producer controls much of a commodity’s global deposits and production capacity.

Saudia Arabia is a good example of a swing producer of oil.

So rare earth stocks find themselves operating in a landscape dominated by a player that can shape that landscape almost to its will. That comes with risks.

Of course, this state of play also offers opportunities. China would not rationally exercise its power to lower prices.

In 2010, for example, China suddenly cut REEs exports to Japan, sending prices higher.

2. Small-cap rare earth stocks are often speculative propositions

While there are many junior rare earth stocks on the ASX, success is not guaranteed for all.

As with resource stocks in general, prospecting explorers incur a lot of risk chasing gold, silver, uranium…or rare earths.

Many rare earth stocks are yet to produce any rare earth metals and their enterprise is exposed to substantial financial risk.

Even if a rare earth stock secures the funding needed to see a project through, it might come up against cost blow-outs or lower than expected ore reserves and grades, impacting the project’s economics — and financial outlook.

3. Natural resource stocks depend heavily on prevailing supply and demand

Companies engaged in mining, extracting, and producing rare earth minerals rely heavily on the prevailing demand for, and supply of, rare earth metals.

Waning international demand can send sales — and stocks — plummeting.

Oversupply, egged on by producers overestimating future demand, can also crater spot prices.

For instance, rare earth metal prices fell from 1958–71 once the large REEs deposit at Mountain Pass, California became operational in 1952…and flooded the market with supply.

Rare earth stocks are also vulnerable to exogenous events beyond their control or budgetary powers.

Certain rare earth minerals may become objects of geopolitical manoeuvring, suffering from embargoes or tariffs.

Of course, sometimes these geopolitical events can have a positive effect on the spot prices of rare earths.

Consider what happened to the price of scandium in the 1980s.

Back then, the Soviet Union was the main source of scandium. When the USSR ceased exports in 1984, the price of scandium rose to a heady US$75,000 per kilogram.

But, highlighting the power of the supply and demand equation, scandium prices fell markedly the following years once US production came online.

4. Substitution — few things are indispensable

As prices of one good rise, alternatives to that good become more attractive.

Similarly, if rare earth materials enter a sustained supply crunch, the elevated prices may force downstream users to seek alternatives — what the industry calls substitutes.

This isn’t just me talking.

Constantine Karayannopoulos, CEO of Neo Performance Materials — a rare earth metals producer — warned in October 2021 that rising prices may lead to more firms switching to substitutes:

‘Even though rare earths are terribly important, they’re not indispensable. Given enough motivation, enough resources and enough brain power, they can be designed out.

‘At today’s prices everybody makes money…but my word of caution is that the industry should be very careful not kill the goose that laid the golden egg.’

If viable, and cheaper, substitutes are found to dominant rare earths applications, REEs prices could fall to form an equilibrium with the prices of the substitutes.

Take, for instance, the giant US conglomerate General Electric Co [NYSE:GE].

In its 2020 sustainability report, GE noted it was researching new technologies to drive improvements in the energy sector…including working on superconductor generators that would ‘eliminate the need for rare earth materials.’

Summary

Geoscience Australia wrote in a 2020 report:

‘With demand forecast to rise over the medium term, Australia has a commercial opportunity to build competitive critical minerals export markets, and to improve the domestic and global strategic supply of critical minerals.’

Demand for rare earth metals is likely to increase as the world entrenches its dependence on sophisticated — and increasingly green — technology.

And Australia — and Australian rare earth stocks — could play a large role meeting this demand.