To see where we’re going, we need to look back at how we’ve arrived at this moment in history.

The 20th century was one of great changes and advancement… especially from 1950 onwards.

In the history of human progress, there was never a better time to be alive.

All the ‘actions’ — Medication. Sanitisation. Financialisation. Innovation. Electrification — provided those of us living in the West with much higher living standards and longer life spans.

A rising tide of prosperity lifted all boats.

An expanding Western World middle class became a major contributor to global GDP growth.

Sadly, we’re witnessing the demise of the middle class.

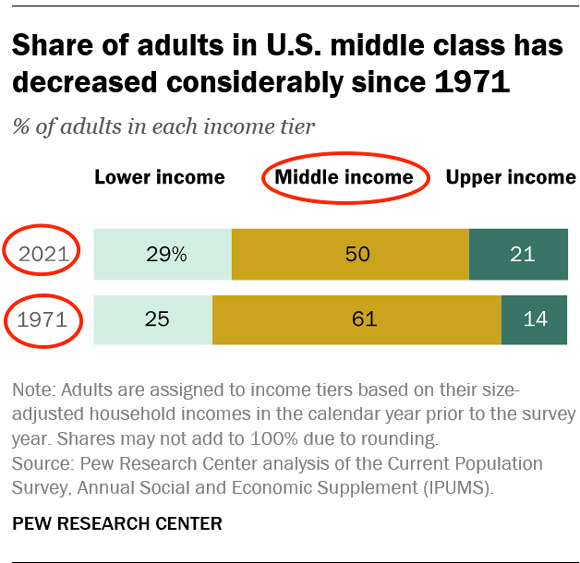

According to the findings of Pew Research (emphasis added):

‘The middle class, once the economic stratum of a clear majority of American adults, has steadily contracted in the past five decades. The share of adults who live in middle-class households fell from 61% in 1971 to 50% in 2021, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of government data.’

|

|

|

Source: Pew Research |

And the trend is being repeated in Australia…

‘[An OECD] study found that the share of people in middle-income households fell from 64 per cent to 61 per cent between the mid-1980s and the mid-2010s.

‘“In Australia, it’s even lower, at 58 per cent,” says Jason Pallant, marketing lecturer at Swinburne University.

‘While the shift in terms of real percentages may not appear major, when you consider that it represents millions of people, it is actually a big issue.

‘It signifies that the rich are getting richer, while the people in the middle are really struggling. Many are not going up from the middle class, but down.’

CPA Australia, March 2020

Robotics and AI are comin’

Due to the relentless adoption of robotics and AI, some believe that the pressure on the middle is set to intensify.

‘I expect that more than one-third of all men in the US between 25 and 54 will be out work at mid-century.’

Larry Summers (former US Treasury Secretary and former President of Harvard University)

ChatGPT has renewed debate over the impact AI is likely to have on the jobs market.

Will it be net positive or negative for employment?

In April 2020, Daron Acemoglu (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and Pascual Restrepo (Boston University) published a Working Paper titled, ‘Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets’.

According to their modelling (emphasis added):

‘Our estimates imply that between 1990 and 2007 the increase in the stock of robots (approximately one additional robot per thousand workers from 1993 to 2007) reduced the average employment-to-population ratio in a commuting zone by 0.39 percentage points and average wages by 0.77% (relative to a commuting zone with no exposure to robots).

‘…or equivalently, one new robot reduces employment by about 3.3 workers.’

Could the Pac-Man-like effect of robots devouring jobs be a contributing factor to the reversal in the US Labor Force Participation Rate?

|

|

|

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data |

In June 2021, Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo published another working paper, ‘Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in US Wage Inequality’.

Here’s part of their findings (emphasis added):

‘…a large share of the changes in the US wage structure during the last four decades are accounted for by the relative wage declines of workers that specialized in routine tasks at industries that experienced labour share declines.

‘We will see that the same pattern holds when we focus on the component of the labor share decline driven by automation technologies.

‘Our framework clarifies why worker groups that specialize in tasks being automated will bear the brunt of these changes and will suffer relative and potentially absolute wage declines.’

In addition to displacing workers, automation can be a wage suppressant.

Inflationary pressures have fuelled rolling work stoppages and demands for higher wages.

But, if the cost of labour rises too much, how long before business owners start looking for lower-cost alternatives?

ChatGPT is the latest leap forward in the advancement of AI…but it won’t be the last.

Will Moore’s Law mean less for workers?

Moore’s Law on exponential growth is often referred to as ‘The Law of Accelerating Returns’.

The greater the number of robots created, the cheaper, smarter and more specialised they become.

Why would you employ someone (with all the attendant IR regulations and multiple leave entitlements) when you can lease or buy a robot or invest in AI for far less AND work it 24/7?

Whether you agree or disagree with this argument, I can assure you that if your competition is gaining a price advantage by utilising automation and AI, then you either adapt or die.

Market Watch reported on the expected momentum in automation and its potential impact on prices, wages and jobs (emphasis is mine):

‘“You get the sense we are seeing increased use of new automation that has even greater potential to reduce costs than in the past,” said Sal Guatieri, senior economist and director of research of BMO Capital Markets in Toronto.

‘“The use of automation, robots in particular, is still relatively limited compared to the number of people employed,” he told MarketWatch in an interview.

‘“It’s getting to the point now that some studies suggest automation will replace almost half of all tasks that workers now do,” Guatieri said.

‘The adoption of smart robots is relentlessly driving down labour costs. By reducing expenses, companies can maintain profits and even cut prices in a intensively competitive global economy.’

This is only the beginning.

Wait until the (less expensive) robot to the (more expensive) worker ratio increases.

Even if jobs are not threatened by technology, the other major suppressant on incomes in the developed world is the rapid progress occurring in the developing world.

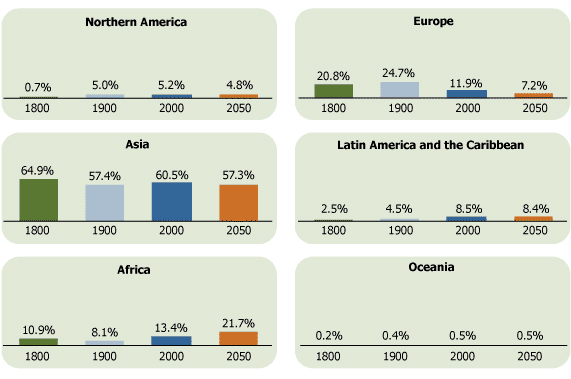

The following chart is the distribution of the world’s population by region since 1800.

|

|

|

Source: Population Reference Bureau |

In 1900, roughly one-third of the world’s population (the US, Europe, Japan and Oceania) enjoyed the bounty of riches on offer.

The Western World prospered while the remaining two-thirds of the world was left behind.

With the rise of China, India and other Asian nations, that dynamic is changing.

Well-remunerated Westerners are facing spirited competition from billions of people who want what we have…a higher standard of living.

Who can blame them?

Get used to lower growth

In view of these strong headwinds — technology and increased competition from the Asian economies — it’s unlikely we’ll see a return to the stellar growth rates of yesteryear.

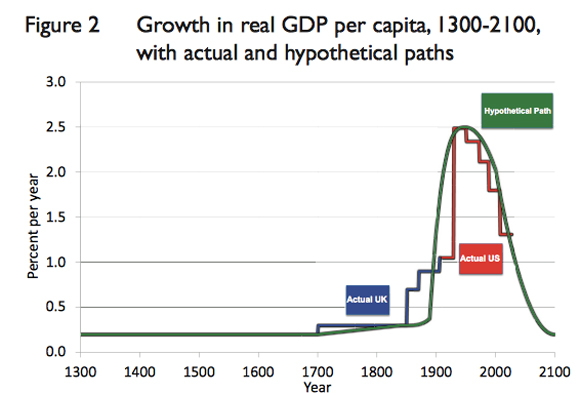

In 2012, Professor Gordon (in his research paper ‘Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds’) provided a probable trajectory of real (after inflation) economic growth for the US (world’s leading) economy.

It’s not a pretty picture:

|

|

|

Source: CEPR |

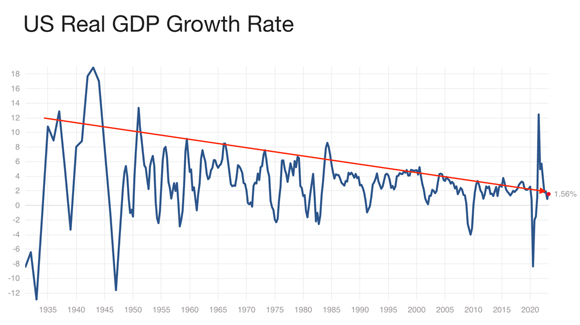

That declining trend, in real (after inflation) US GDP growth, is evident in the following chart…from 1935–2023.

|

|

|

Source: Multpl |

The shrinkage in real GDP growth is occurring at a time when more and more debt is being injected into the economy.

How much debt can an economy — even one the size of the US — support, before it collapses under the weight of servicing costs and defaults?

What’s going to happen to growth when this current (and very protracted) debt super-cycle comes to a crashing end?

Professor Gordon’s predicted path of GDP growth could look overly optimistic.

Dealing with the legacy

The golden 20th century has left us with a debt, demographic and deficit legacy.

The only way the 21st century can even hope to fund 20th century (welfare and perpetual growth) promises is with a real economic growth rate in excess of 2% per annum…ad infinitum.

Given the headwinds we face, this growth rate does not appear to be achievable on a year-in and year-out basis.

Yes, we may have glimpses of an above-average growth rate every now and then, but these will be fleeting. The trend is for lower lows.

The 20th century has bequeathed us a legacy for which there is no precedent.

The Great Depression was a result of the world becoming a touch too indulgent from the prosperity of the 1920s.

However, there are major differences between then and now.

Debt levels were much lower than today.

People were far more self-sufficient…less reliant on government.

Entitlements barely existed.

Life expectancies were lower…less elderly for the system to support.

Retirement planning was a luxury enjoyed by a privileged few.

This may seem difficult to comprehend, but the system we have today is infinitely more fragile than the one that existed in 1929.

Our current economic and financial system has evolved from the prosperity of the 20th century. Unless ‘glory day’ growth rates can be repeated, our past success will have sown the seeds for our future failure.

We’re in unchartered waters.

The only reliable guide we have is the blindingly simple logic of economist Herbert Stein, ‘If something cannot go on forever, it will stop’.

Logic and math make a compelling argument as to why the current system of over-indebtedness and over-promise cannot continue unchanged.

Unfortunately, there is no easy way to lower society’s expectations and entitlements.

Politicians won’t do it.

Therefore, the job will fall to the market — which is why I believe a prolonged and very painful bear market is in our future.

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia