Editor’s note: What’s the biggest danger to Australian investors in 2022?

According to our Editorial Director, Greg Canavan, it’s this.

Vern Gowdie, however, is not looking at just Australia right now. He sees a systemic risk building that could soon swallow the whole financial world. See below…

‘A blind pool, also known as “blank check [cheque] underwriting” or a “blank check [cheque] offering,” is a direct participation program or limited partnership that lacks a stated investment goal for the funds that are raised from investors.’

Investopedia

The market is where supply meets demand to agree upon a price.

In a bull market, more money (demand) is chasing fewer shares (supply).

Price goes up.

A bear market is when more shares (supply) chase less money (demand).

Price goes down.

It’s a time-honoured cycle.

One that should hardly warrant mentioning…but it does.

Why?

Because it can take the market a very long time to honour the cycle.

In the prevailing years, people forget or think this cycle is different or have no experience of the ‘ebb and flow’ pricing mechanism.

Any student of market history knows each cycle displays similar behavioural patterns.

Sometimes we are more excitable than at other times and our depressive episodes can be over and done with or take longer to express themselves.

However, there is a rhyming pattern.

For instance…

‘With stock prices rising, small investors were tantalized by the prospect of bigger returns on their savings than bank accounts would pay in interest.’

The above extract is from this History.com article:

|

|

|

Source: History.com |

In a low interest rate environment, solid (and at times, sustained) double-digit market returns can be difficult to ignore. The lure oftentimes is too great to ignore.

A booming market brings forth all manner of opportunities.

Positive index returns become oh so boring.

Surely there are ‘insider’ deals out there that can put those index returns in the shade?

Promoters know ‘wink, wink, nudge, nudge opportunities’ promising to multiply your capital many times over can be so tantalising they make people go weak…in the head.

Popular delusions

In 1841, when Scottish author Charles Mackay published Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, he was only 27 years of age.

His timeless work showed experience well beyond his age.

Even in the 19th century, Mackay had plenty of market history to draw upon for his book.

Tulip Mania. Mississippi Land Bubble. South Sea Bubble.

On page 88 of his book, Mackay introduces readers to the (completely delusional) concept of blind pool investing in the South Sea Bubble (emphasis added):

‘[T]he most absurd and preposterous of all [the new projects of 1720 in London], and which showed, more completely than any other, the utter madness of the people, was one started by an unknown adventurer, entitled “A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” Were not the fact stated by scores of credible witnesses, it would be impossible to believe that any person could have been duped by such a project.’

The seeds of absurdity can only bear fruit in fertile ground.

And there’s nothing like a boom to put plenty of ‘manure’ in the investing soil.

In a bust, the land is so barren, only the hardest of investments can survive.

In 1719/20, people must have been so blinded by greed, they lost all objectivity…except for the promoters of these pools. They knew exactly what they were doing.

As a boom gathers momentum and captures imaginations, what would normally be considered laughable becomes serious business.

Demand far outweighs supply.

In wanting to capitalise on this lopsided equation, clever operators ‘invent’ supply to part the fools with their money.

Roll up, roll up, invest in unknown and, as yet, unidentified companies.

Blind pools.

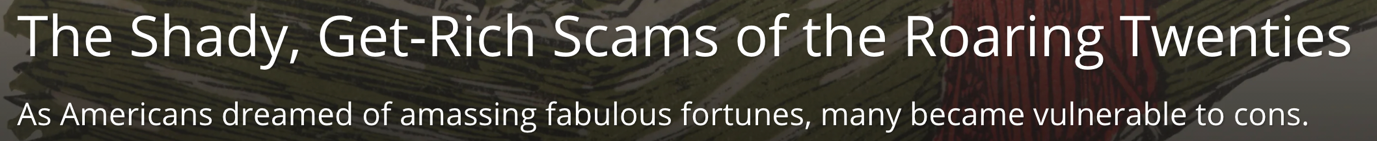

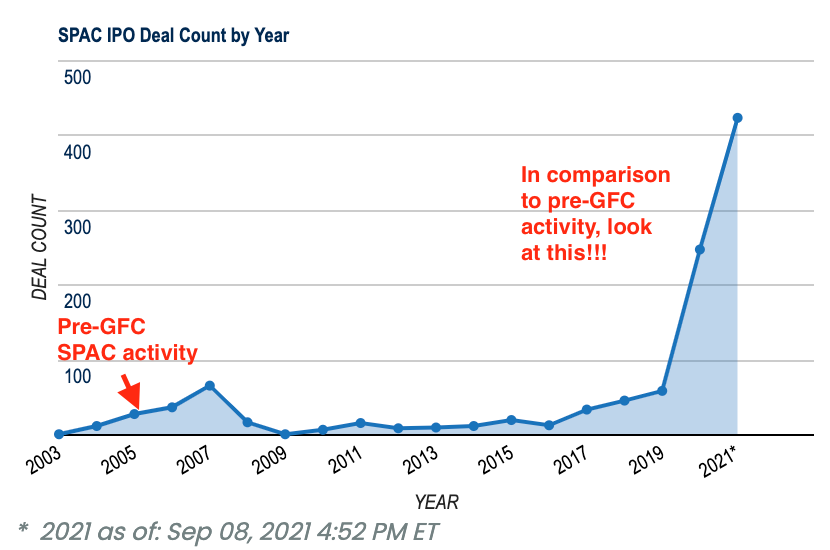

The following chart plots the price of the South Sea shares and the volume of monthly start-ups (blind pools). To align with the share price scale, the number of monthly start-ups have been multiplied by 10…at the peak in June 1720, the black dot is at 880 (88 start-ups were launched).

|

|

|

Source: Andrew Odlyzko |

The emotional range of investors ‘before, during, and after’ the bubble peaked is as identifiable as it is understandable and predictable.

If you want to capitalise on the mob’s temporary lapse in judgement, then you get this stuff to market — ASAP — before people come to their senses.

The 1920s

200 years is a long time.

Previous generations take their lessons to the grave.

The Roaring Twenties provided plenty of fertile soil for the seeds of absurdity to germinate.

Get rich schemes and blind pools proliferated.

The mind is a funny thing…trying to figure it out is beyond the scope of this amateur psychologist.

We know ‘if something is too good to be true, then it usually is’, yet something compels people, on the one hand, to acknowledge this truth and yet, on the other, to completely ignore it.

Why?

The only logical answer is ‘we expect hope to triumph over experience’.

The 1920s and 1930s make for fabulous study in market psychology.

Two opposite decades.

The lasting effects of The Great Depression era meant it would be almost 60 years before the allure of easy wealth would once again prove too enticing to resist.

The pre-1987 crash period is one I remember well.

There was genuine fervour for all things shares.

The movie Wall Street captured the mood of the times…‘greed is good’.

This was the fertile ground upon which blind pools could flourish.

Then came the 1990/91 recession and I can tell you from experience, the investing land was fallow.

Pre-GFC

This was another manic period in market history.

Margin lending. Mortgage securitisation. CDOs.

If Wall Street could have developed even a wafer-thin case for bringing a product to market that bet on ‘two flies going up a wall’, it would have AND I have no doubt investors would’ve piled into it.

And no genuine boom would be complete without our old mate…the blind pool.

|

|

|

Source: Barron’s |

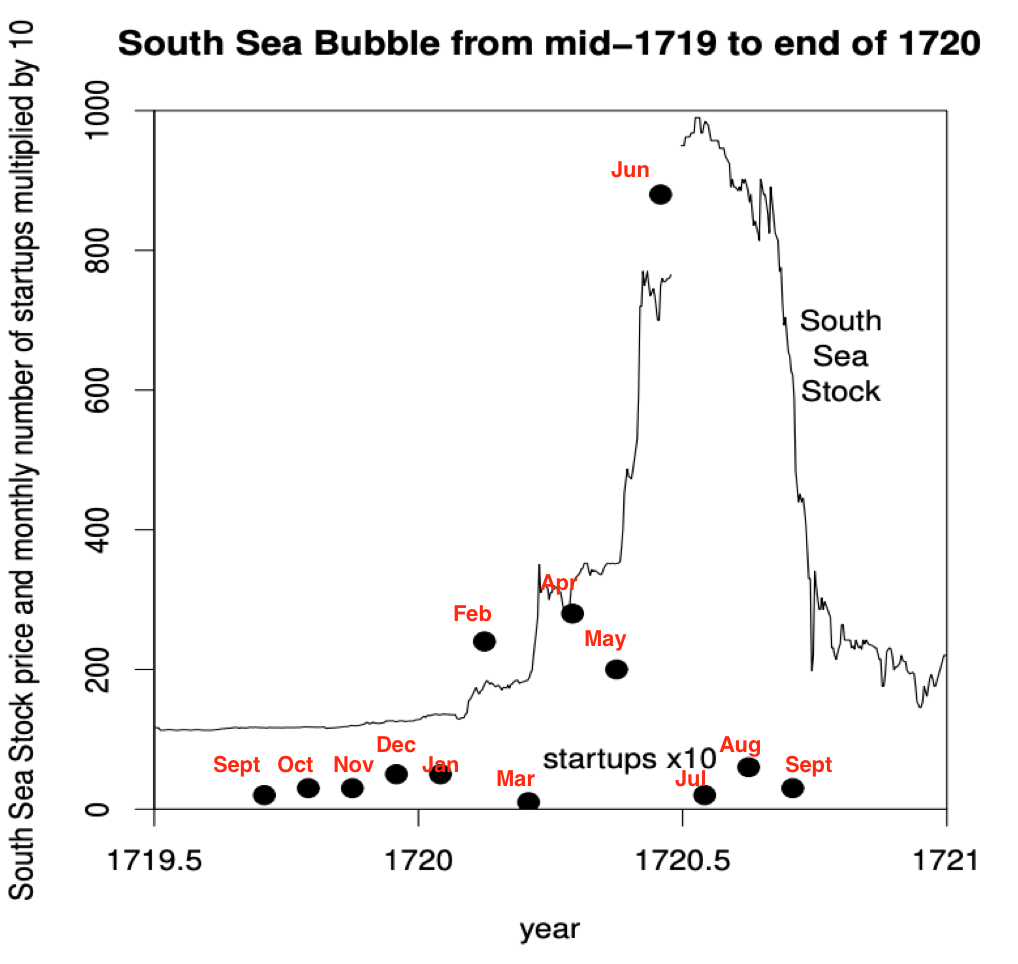

To quote from the article (Seinfeld fans will get the reference to George Costanza)…

‘Wall Street has latched onto an ingenious approach to raising capital. It’s an equity structure that George Costanza would love: the IPO about nothing.

‘Over the past two years, investors have snapped up $2 billion worth of shares in a new breed of blank-check stock offerings. It’s the return of the blind pool, gussied up with a nicer name — the special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC.

‘Whatever you call them, the game is pretty simple: You buy shares of a company with no operations, and then that company takes the cash and goes shopping for something to buy.’

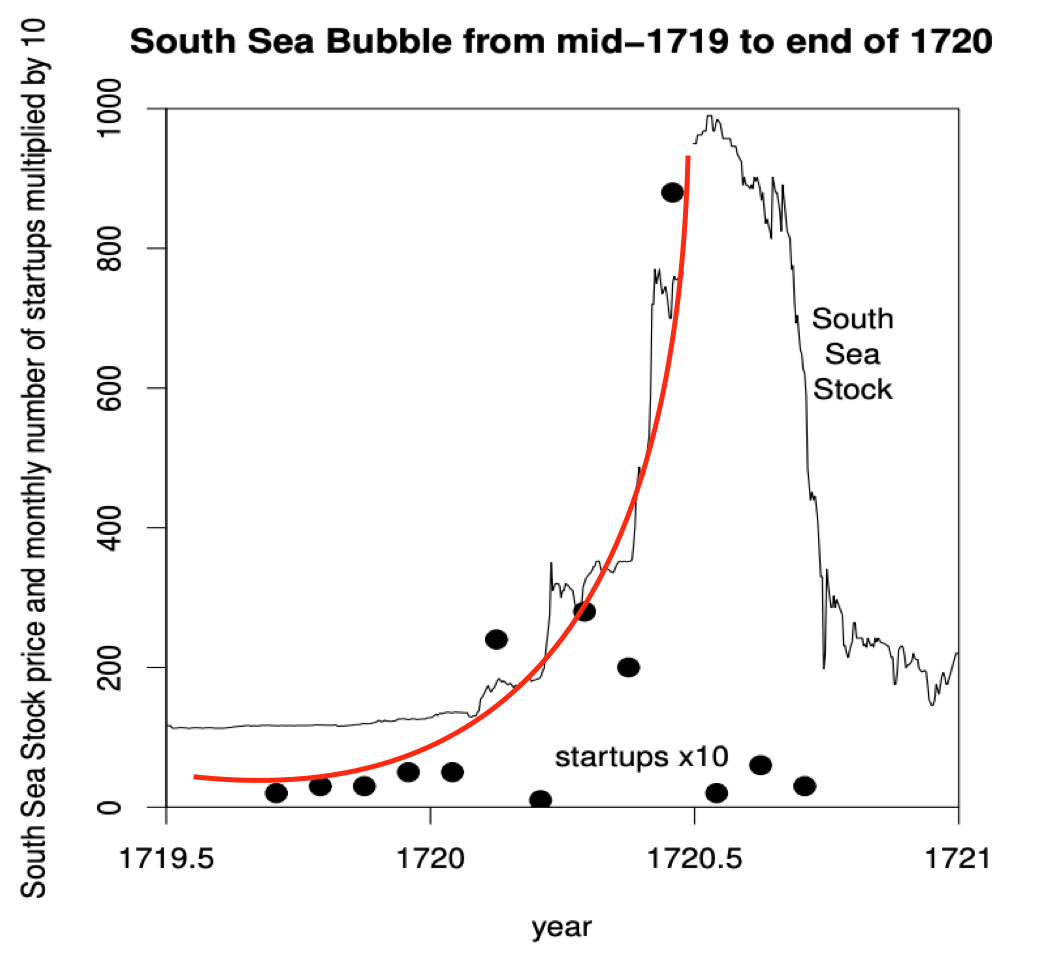

In the more mature phase of every major market boom, blind pools or as they are now labelled, Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs), make an appearance.

These investment vehicles are the swallows indicating the market’s summer has well and truly arrived.

And, if the seasonal patterns of past markets are repeated, it means a bitter market winter is soon to follow.

Present day

In what, I believe, will go down as the greatest bubble ever blown, you’d expect SPACs to show up for the party.

And boy, they’ve arrived in numbers over the past two years.

The following table is from SPACInsider:

|

|

|

Source: SPACInsider.com |

This chart takes the numbers from the above table and includes the pre-GFC SPAC activity…

|

|

|

Source: SPACInsider.com |

Hmmm…déjà vu anyone?

|

|

|

Source: Andrew Odlyzko |

From 1720 to 2020, very little has changed in behavioural patterns.

Boom times bring forth the same animal spirits upon which savvy (and unscrupulous) operators capitalise on.

If history is any guide, the current exponential proliferation of SPACs should serve as a countercyclical warning sign to retreat to a position of safety.

Take money off the table…only when the money is in the bank are the profits real.

Dial back speculative bets that are conditional upon an increasingly bullish outlook being sustained (almost) indefinitely.

Reduce equity exposure to a level where a 50–70% downturn (that could take two or more years to play out) will not adversely affect your lifestyle and plans.

Blind pools can only exist in an environment where investors are blind (or have turned a blind eye) to the (substantial) risks building within the system.

Now is the time when investors should be looking at the market with eyes that are not only wide open but have the peripheral vision to see the historical landscape…and it clearly shows…danger ahead.

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

For The Daily Reckoning Australia

Editor’s note: As you’ll have noticed, we’re taking a break from normal scheduling this week at The Daily Reckoning Australia. If you believe the asset markets are living on borrowed time, you need to read the investment research we’ll be releasing from Vern this Friday. It’s called Code Red. It contains some startling information on how this ‘Everything Bubble’ could end in 2022. And a five-part guide to surviving this end with your wealth intact. Keep an eye on your inbox for it. Now it’s over to Jim!