‘The invention of debt and the emergence of interest to incentivise lending is the most significant of all innovations in the history of finance.’

Thus writes William Goetzmann in Money Changes Everything, his insightful tome on the birth of finance.

Interest makes lending attractive. In turn, lending helps borrowers smooth their consumption and bring their future cash to bear on their present problems.

Well-greased, the economic machine starts turning.

An important upshot of interest, however, is its close relationship to the productivity of capital.

Imagine you’re a wealthy merchant in Mesopotamia called on by a farmer to lend him X amount of money to cultivate a farm.

You could lend him the money with interest, or you could buy the land yourself and cultivate it.

If the gain from cultivating the land far exceeds the gain from charging interest, you will not lend.

Therefore, the interest charged must have some relation to the productivity of the capital extracted with the help of the loan.

Nicholas Barbon summarised this idea in the 17th century by saying that ‘Interest is the rent of stock (i.e: capital), and is the same as the rent of land.’

This connection to the fruit debt bears is very important.

Modern finance can make interest seem like an abstruse concept abstracted away from anything tangible. But that is far from the case.

As economic historian Edward Chancellor wrote in The Price of Time:

‘Interest has always been with us because resources have always been scarce and must be rationed somehow, because wealth is unequally distributed between creditors and borrowers, and because, as Bohm-Bawerk says, “interest is the soul of credit.” Interest exists because loans are productive, and even when not productive still have value. It exists because those in possession of capital need to be induced to lend, and because lending is a risky business.’

The etymology of interest itself hints at the thrust of the argument so far.

Goetzmann notes in his book that the word for interest in ancient Greek, tokos, refers to the progeny of cattle. The Egyptian word for interest, ms, means ‘to give birth’.

As Goetzmann summarises (emphasis added):

‘All these terms point to the derivation of interest rates from the natural multiplication of livestock. If you lend someone a herd of thirty cattle for one year, you expect to be repaid with more than thirty cattle. The herd multiplies—the herder’s wealth has a natural rate of increase equal to the rate of reproduction of the livestock. If cattle were the standard currency, then loans in all comparable commodities would be expected to “give birth” as well. And that brings me to the neutral rate of interest.’

And that leads us to the natural rate of interest.

The neutral rate of interest and why it is important

The natural — or neutral — rate of interest is the real interest rate compatible with a stable level of economic activity where the price level is constant.

It is the natural rate of interest that neither impedes nor stimulates the economy — the equilibrium rate, if you will.

Or, as Gregory Mankiw defines it, it’s the real interest rate ‘at which, in the absence of any shock, the demand for goods and services equals the natural level of output’.

The natural rate is important for central banks, who benchmark their interest rate decisions on the perceived real natural interest rate.

For instance, if the market rate is below the natural rate, it can excite the economy.

Conversely, market rates above the natural rate can dampen activity.

Take the Dallas Fed president explaining the importance of the neutral rate on his decision-making:

‘The reason is that, despite the relatively wide confidence bands around these estimates [of the natural rate], they can provide an indication, albeit imperfect, of whether our monetary stance is accommodative, neutral or restrictive. Making a judgment on the stance of monetary policy is a key part of the job as a central banker.

‘Monetary policy is accommodative when the federal funds rate is below the neutral rate. When this is the case, economic slack will tend to diminish—the economy will tend to grow faster, the unemployment rate should decline and inflation should tend to rise. When the federal funds rate is above the neutral rate, monetary policy is restrictive. When this is the case, economic slack will tend to increase—economic growth will tend to slow, the unemployment rate should tend to rise and the rate of inflation should be more muted or decline. The challenge for the Federal Reserve is managing this process and getting the balance right.’

And here’s our own Reserve Bank clearly outlining just how pivotal the neutral interest rate really is to central bank policy-making:

‘Central banks, including the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), monitor the neutral interest rate for a number of reasons. The neutral interest rate provides a benchmark for assessing the current stance of monetary policy. If the real policy rate — that is, the cash rate less expected inflation — is below the neutral rate, then monetary policy is exerting an expansionary influence on the economy. If the real policy rate is above the neutral rate, then monetary policy is exerting a contractionary influence on the economy. Estimates of the neutral interest rate can also be useful for understanding issues such as whether monetary policy has become more or less effective over time.’

These definitions are dry compared to one proposed by English philosopher John Locke (emphasis added):

‘What the stated rate of interest should be in the constant change of affairs, and flux of money, is hard to determine. Possibly it may be allowed as a reasonable proposal, that it should be within such bounds, as should not on the one side quite eat up the merchant’s and the trademan’s profit, and discourage their industry; nor on the other hand so low, as should hinder men from risquing their money in other men’s hands, and so rather choose to keep it out of trade, than venture it upon so small a profit.’

For many years after the global financial crisis, the neutral rate was thought to be close to zero.

Hence why many central banks followed the neutral rate down and lowered their official interest rates for fear of being too restrictive.

Now, however, questions are rising whether the neutral rate is getting up from the canvas and pushing well above zero.

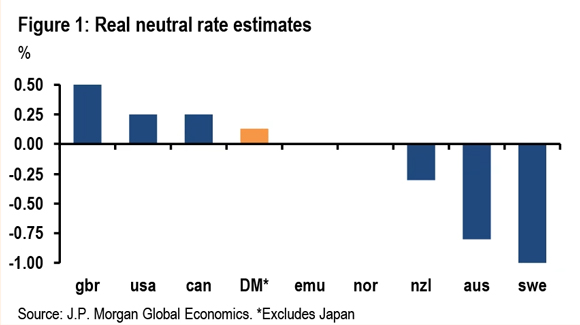

In a research note released last week, a team at JPMorgan mused that the neutral rate may be rising, making it more difficult for central banks…and making it likelier official interest rates will hover higher for longer.

The note states (emphasis added):

‘We attribute the ineffectiveness of last decade’s low-for-long stances to powerful disinflationary forces unleashed by the GFC outside the control of central banks. Importantly, conditions have changed dramatically. In contrast to last decade’s post-GFC balance sheet adjustment and regulatory tightening, the pandemic and has improved private sector balance sheets and created pent-up demand. In addition, fiscal policy shocks during this cycle have generally been positive thus far, a radically different backdrop to the aggressive European and US tightening through the first half of the last expansion. Finally, the supply shocks related to the pandemic have altered the inflation process in a way that is likely raising short-term inflation risk premia. In all, these developments suggest that neutral policy rates have moved higher from estimates at the end of the last expansion.’

|

|

| Source: JPMorgan global economics |

Note, too, that JPMorgan suggests Australia’s own real neutral rate is well in the negative territory.

Let’s go back to the RBA’s earlier formulation:

‘If the central bank’s real policy rate — the cash rate less expected inflation — is below the neutral rate, then monetary policy is exerting an expansionary influence on the economy. If the real policy rate is above the neutral rate, then monetary policy is exerting a contractionary influence on the economy.’

The current cash rate is 3.35% and the longer-term inflation expectations are about 2.5%. Meaning the real policy rate is about 0.85%, well above the implied neutral rate estimated by JPMorgan.

If JPMorgan’s estimates are right, Australia’s monetary policy is tightening the screws on the economy.

Watch out!

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

For Money Morning