Two days ago, Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers delivered the Australian Federal Budget. One of the notable points was that this was the first budget surplus in 15 years.

$4.2 billion surplus, or 0.2% of our gross domestic product.

This was considered a major achievement. Finally, our government has delivered the all-important ‘Budget Surplus’!

It’s been elusive. Many sat through past Budget nights hearing how the surplus would be delayed a couple more years as the government finds a new cause or group to ladle our tax revenue. That, or because the forecasted receipts from businesses and households were less than expected.

So the government is patting itself on the back and the media is highlighting how there’s a budget surplus!

In context of how this is the first in 15 years, it’s commendable.

But the forecasts show there won’t be a repeat performance, and you shouldn’t hold your breath that it’ll happen again any time soon.

What’s more concerning are some of the measures the government plans to implement this coming year to try to ‘help’ the Australian population through these tough times.

But let’s look at the budget surplus and how we’re being misled to take this as a suitable measure for evaluating the government’s fiscal responsibility.

Deep in debt with little desire to get out

What is often ignored when the media reports on the Federal Budget is the government’s financial position. This is how much the government owes its creditors, which is also what we’re meant to pay via our taxes.

As of now, our net government debt is estimated at just under $550 billion or 21.6% of our GDP.

This is a pretty significant figure, though not dire.

Put our government budget into perspective, let’s say it made $100,000 a year. This year it’s projected to have a surplus of $200. Meanwhile, the total outstanding debt (after deducting our savings and liquid assets) is $21,600.

It might not sound that bad. I daresay that many households are in a more precarious financial situation given that they have a massive mortgage that’d dwarf the government’s outstanding debt.

Perhaps that’s why we’ve seen the government continue to spend beyond its means. That and the low interest rate environment that many have come to take for granted, at least until the last few months.

And this is where we ought to be concerned.

The government has several advantages over households in that it makes the rules and owns a lot of assets. Its goal is to implement policies that are meant to help the ordinary Australian become more prosperous. So it can also change laws that could impact its revenues and expenses, although it can only do so within the confines of what the ordinary voter will tolerate.

Such advantages give the government a lot of leeway. But it’s the fact that the government has such a good handicap that it raises red flags when it continually falls short of its standards.

When you look at it from this angle, you see that our government has a track record of fiscal incompetence. Policies haven’t improved the prosperity of the nation, given it receives less than its expenditures. In turn, it’s owing more to its lenders year after year.

So it’s failing to score goals despite widening them time and again.

Let me present some numbers to back up my claim.

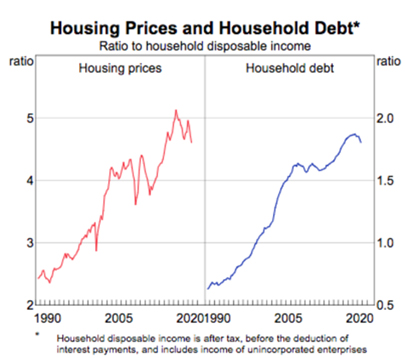

Household debt in Australia has ballooned over time. Based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the average household debt at the end of the 2022 financial year was $261,492, compared to an average disposable income of $139,064. This means an average household owes almost $2 for every $1 it earns each year. It’s worth noting that you need to go back to the mid-1990s to see the average household owing as much debt as it earned annually.

The figure below illustrates this:

|

|

| Source: ABS, RBA, Corelogic |

All this happened as property prices boomed.

Now I get how you may rebut my point by saying that Australian households are benefiting from rising property prices. They can stomach the higher debt burden. However, this creates an attitude of debt reliance. It’s unhealthy because it encourages spending beyond your means on the back of potentially illusory wealth.

Debt is someone else’s wealth. If you’re owing more as time passes, that’s going to hurt you in the long run. It’s that simple.

Thanks to a prolonged period of falling interest rates, we’ve been conditioned to think that we can rely on debt, even letting it balloon over time.

If only it’s that easy! History shows otherwise.

A rude shock and potential reckoning

We’ve been a lucky country in many ways. Many countries experienced a reckoning of sorts during 2007–09 when the property bubble collapsed, causing much heartache and despair.

We managed to ride an unprecedented property boom back then given the Reserve Bank of Australia reduced the interest rate and our government spent billions propping up our economy.

For this, many Australians are complacent about what could happen in the future. Even the rapid interest rate rises in the past year haven’t really hit home yet.

It might start to bite when many mortgage loans come off their fixed interest rate period in the second half of the year.

The government has set aside $3 billion to provide relief to households that’re facing energy bill pressures, which is part of the $14.6 billion set to ease the cost of living.

But if the economy slows down significantly as the fallout of rising interest rates and mortgage repayments hits, would these be enough?

Not to mention that businesses could also face shrinking revenues as consumer confidence slumps.

Does the government have enough borrowing capacity to help soften the impact on ordinary Australians?

Unlike Japan where the population owns much of the government’s debt, our creditors are foreign lenders. They’re less likely to cut us much slack as they’ve no loyalty towards us, it’s strictly business.

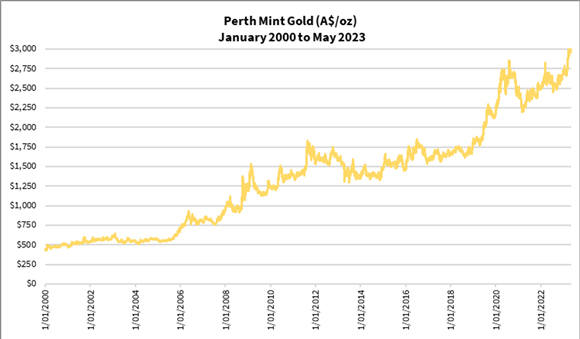

That’s why our Australian dollar has remained weak against the US dollar and gold.

Which brings me to this graph of the price of gold in Australian dollar terms since 2000:

|

|

| Source: Thompson Reuters Refinitv Datastream |

For more than 23 years, gold has increased six-fold relative to our dollar. This is a good reflection of how much purchasing power our currency has lost, thanks to our collective financial mismanagement.

Many households have seen their wealth increase in dollar value, make no mistake about that. But I’m confident that the vast majority of Australians are now able to buy less despite having more.

What should this tell you?

The insanity of debt dependency has cost us a lot. It’d be great if it can come to an end. But it comes with much pain.

Soften the impact with sound money, gold. Change your mindset and save yourself some heartache.

Get ahead of the others now, before they wake up to this reality and clamour on board!

God bless,

|

Brian Chu,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia