Germanium and gallium may not be household names like gold or silver, but in the high-tech domain, they act as unsung heroes.

Sadly…China completely dominates them.

We use these metals in semiconductors for our computers, cars, medical equipment and military.

Semiconductors are quickly becoming the lifeblood of industry and metals like these will determine the winners and losers of our future.

China has also included Graphite in its list of restricted minerals, a mineral crucial for our EV batteries.

With these restrictions, China limits our ability to compete with its homebuilt EVs and take steps to move away from fossil fuels.

Looking at the full list of bans, we can see China wants to hold the keys to our future.

So why not just change to another metal for our semiconductors?

Well, apart from their roles in semiconductors, these metals also have unique applications.

We use Germanium for specialised camera lenses and fibre optics.

It’s found in military tech like night-vision equipment and infrared sensors on ships, tanks and missiles.

Gallium, and its hard-to-make cousin, gallium arsenide, plays a vital role in solar cells and radio frequency chips.

These can take higher temperatures and produce less noise, making them crucial for cell phones and satellites.

It’s also found a new role in cutting-edge chips used in EVs that operate 20x faster and charge 3x more quickly – while being half the weight and size.

So why did China restrict these metals and minerals, and what can we do?

Command and control

China is playing tit for tat with the US, ramping up its export restrictions on the grounds of ‘national security‘.

Its latest moves can be seen as a response to the US export restrictions to slow China’s access to semiconductor technologies. Steps that China avoids in other ways.

Last month China allegedly stole the technology to make the chips and gave the thief a new job at Huawei.

So if our restrictions fail, how will China’s moves affect our industry?

In the grand scheme, the restrictions won’t be catastrophic.

In 2022, the US and EU combined imported around US$190 million in germanium.

Meanwhile US producers last year imported approximately US$220 million of Gallium Arsenide for their chips.

If we consider their trillion-dollar trade balance sheets, it’s a drop in the bucket. Thankfully, alternative countries like Australia do hold these resources, but it’s still early days.

Analysts from Eurasia Group described China’s export restrictions as ‘a warning shot, not a death blow’.

But it’s one we shouldn’t ignore.

And it’s just one of the ways Beijing is showing it wants to exert more control over the global supply of resources.

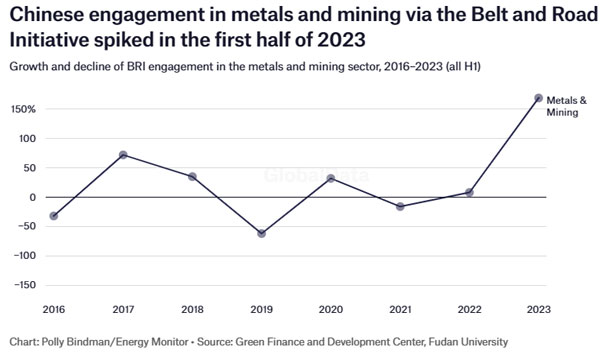

Research shows the value of Chinese investments and contracts in metals and mining exceeded $10 billion in the first half of this year.

That’s a 131% increase compared to last year.

| |

| Source: Energy Monitor |

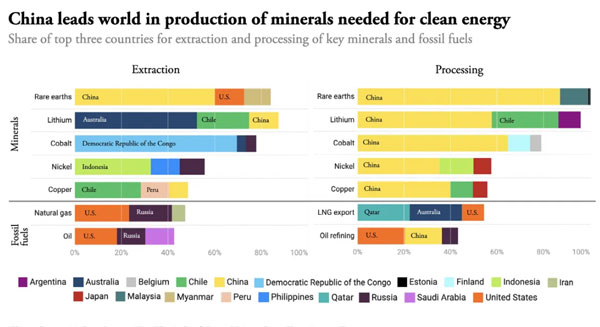

China also holds a massive monopoly over the processing and refinement of these critical metals.

| |

| Source: Canary Media |

So how do we go about navigating this?

Friendshoring

While China’s production capacity is vast, it is not the sole player.

Countries like Canada, Belgium, and Australia are stepping up their efforts to fill in the supply.

Similar efforts happened after Russia banned gas exports into Europe at the start of the Ukraine invasion.

In an effort known as ‘friendshoring’, Western-aligned countries are creating supply chains that leave players like China and Russia out in the cold.

When Australia released its critical minerals strategy this year, it noted that ‘friendly‘ foreign investors would be welcome to invest in Australia.

Resource Minister Madeline King commented on the strategy, saying:

‘Like-minded partners can build new, diverse, resilient and sustainable supply chains as part of a global hedge against concentration.’

We then blocked China from investing in many lithium and rare earth companies.

It seems lessons have been learnt from the past.

An overreliance on China as a trading partner is something Australia clearly wishes to avoid.

For us, the opportunity to develop our critical minerals is too lucrative to pass up.

Untapped wealth, known potential

Australia has been a heavyweight in commodities for decades.

But the new shift towards green and high-tech industries has opened the spotlight to Australia’s potential.

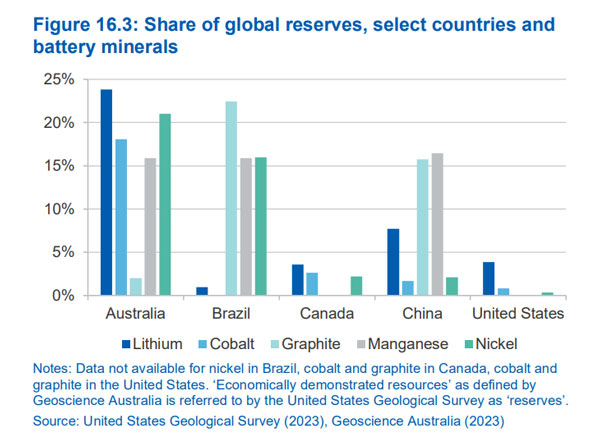

This is nothing new to our readers, but it’s worth understanding just how much we hold in reserves.

| |

| Source: Industry.gov.au |

We see a similar story in Rare Earth Elements (REEs), which could fill these new supply gaps.

Ahead of the game on the ASX, we have players like Lynas Rare Earths [ASX:LYC] and Arafura Rare Earths [ASX:ARU].

But there is also a growing list of smaller hopefuls that cover the gambit of necessary resources for the future.

The metals of the future, like Neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium, are still off the radar for investors.

But all will be critical for future high-strength alloys and advanced magnets for motors and turbines.

Looking at Australia, we can see the market is still young.

20 ASX companies seeking to produce rare earths are valued under $50 million each and most struggle to secure funding.

A good example of this is Northern Minerals [ASX:NTU]. The company aims to challenge China’s 94% monopoly of dysprosium for use in EVs.

The company is trading at 3 cents with a market cap of just under $200 million. But even in its infancy, geopolitical players watch it keenly.

On Tuesday, the company asked the Foreign Investment Review Board to probe whether recent share buys were a covert attempt by Chinese interests to take control.

This comes seven months after Treasurer Jim Chalmers moved to block Chinese interests in increasing their stake from 9.81% to 19.9%.

But as we block these investments, little Australian capital is there to fill the gap.

The challenge for investors and miners is the difficulty of processing and the lack of transparency around pricing in the market.

Here the Australian government can do better. More investment must flow into this space.

Thankfully, we’re seeing some progress, with the Albanese government recently promising a $2 billion expansion to the critical minerals financing.

But we need to set bigger goals to capture the downstream processing of these resources.

The Final Verdict

China’s decision to restrict these exports underlines its pivotal role in the global tech supply chain.

But the actual impact of the bans may be more symbolic than seismic.

Still, it’s a stark reminder that in the world of geopolitics and global tech supremacy, raw materials can serve as powerful pawns on the international chessboard.

The unfolding battle will test the resilience of the global tech sector in an interesting way.

It will also test the diplomatic agility of Australian and Western powers.

For investors, it opens the door to small companies that will capitalise on the changing landscape of supply chain, whether for geopolitical or environmental reasons.

In any case, Australia stands to benefit.

Regards,

|

Charlie Ormond,

Editor, Fat Tail Daily