There are decades where nothing happens…and there are weeks where decades happen.

In the hyperspeed smartphone age, it didn’t even take weeks but days.

In the blink of an eye, Silicon Valley Bank collapsed. It was the biggest such collapse since Washington Mutual in 2008.

SVB’s failure precipitated another — that of Signature Bank. In the span of a few days, the US saw its second- and third-biggest bank failures in its history.

How did this happen?

Silicon Valley Bank: the history

Silicon Valley Bank was a bit of an outlier.

Founded in 1983, the bank carved out a niche as the go-to bank for start-ups and venture capital. Silicon Valley was its name and client base.

The bank served half of all venture-backed businesses in the US and nearly half of all the VC-backed tech and healthcare stocks that went public last year.

SVB was the bank for Silicon Valley.

It offered the Valley traditional banking services but also issued ‘venture debt’ to fledging enterprises. SVB even invested in many of the VC and portfolio companies it served.

Silicon Valley Bank directly invested in big names like Sequoia, Accel, and Kleiner Perkins.

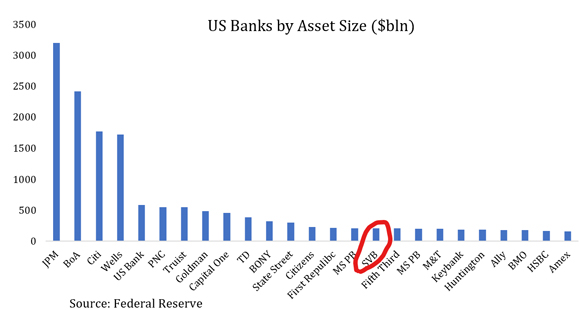

The bank grew to become the 16th-largest bank in the US. And it owed a lot to the pandemic for its size.

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

SVB’s pandemic boom

Given the symbiosis of SVB and Silicon Valley, one can consider the former a proxy of the latter’s fortunes.

And big paper fortunes were being made in Silicon Valley during the COVID-19 boom as retail and VC capital alike flooded the stock market.

SVB’s clients were predominantly businesses, so when these businesses raked in cash from venture capital and hot equity raises during the pandemic, they parked the cash with SVB.

The bank’s deposits mushroomed.

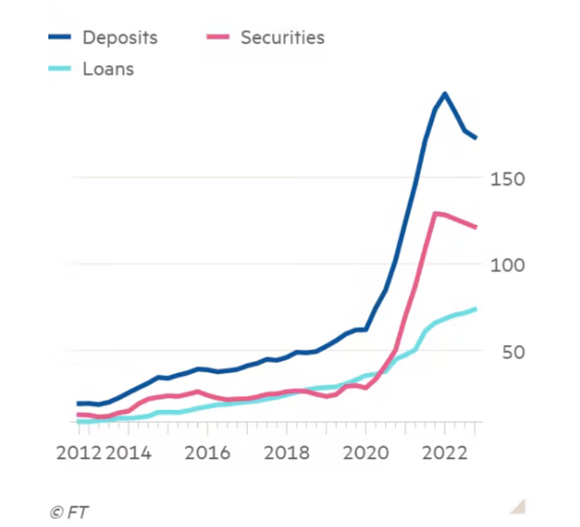

Silicon Valley Bank’s deposits tripled in two years to US$189 billion:

|

|

| Source: Financial Times |

The seed of its failure lay in its initial success.

US$157 billion of that US$189 billion belonged to just 37,000 accounts. 37,000 accounts all in the same industry, susceptible to its ebbs and flows…and its herd psychology.

These deposits were also well in excess of the US$250,000 FDIC deposit-insurance cap.

Imperceptibly, SVB was inching towards disaster.

As Financial Times’ (FT) Robert Armstrong writes:

‘With the explosion of speculative financing in the coronavirus pandemic boom, deposits (dark blue line) rose super-duper fast. SVB’s core customers, tech start-ups, needed somewhere to put the money venture capitalists were shovelling at them. But SVB did not have the capacity, or possibly the inclination, to make loans (light blue line) at the rate the deposits were rolling in. So it invested the funds instead — overwhelmingly in long-term, fixed-rate, government-backed debt securities.’

That decision was fatal.

Moody’s sours the mood

Early last week, risk assessment company Moody’s Investors Service told SVB’s management it was preparing to downgrade the bank’s credit.

Never good news, the bank tried to prevent the downgrade.

That attempt sealed SVB’s fate.

As Reuters reported:

‘Worried the downgrade could undermine the confidence of investors and clients in the bank’s financial health, SVB Chief Executive Greg Becker’s team called Goldman Sachs Group bankers for advice and flew to New York for meetings with Moody’s and other ratings firms, the sources said.

‘The sources asked not to be identified because they are bound by confidentiality agreements.

‘SVB then worked on a plan over the weekend to boost the value of its holdings. It would sell more than $20 billion worth of low-yielding bonds and reinvest the proceeds in assets that deliver higher returns. The transaction would generate a loss, but if SVB could fill that funding hole by selling shares, it would avoid a multi-notch downgrade, the sources said.

‘The plan backfired.

‘News of the share sale spooked clients, primarily technology startups, that rushed to withdraw their deposits, upending the capital raising. Regulators stepped in on Friday, shutting down the bank and putting it in receivership.’

SVB’s 8 March fire sale

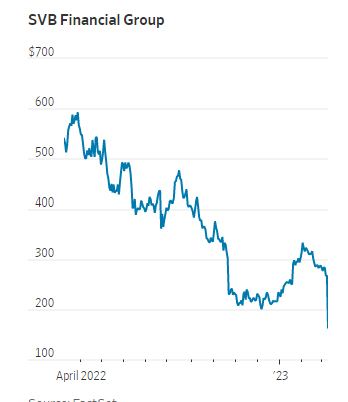

Worried about the Moody’s downgrade and dwindling client deposits following a market downturn, Silicon Valley Bank announced a fire sale on Thursday, 8 March.

SVB tried to couch the sale in optimistic terms, stating in a SEC filing:

‘A sale of substantially all of our AFS (available-for-sale) securities will enable us to increase our asset sensitivity, partially lock in funding costs, better insulate net interest income (NII) and net interest margin (NIM) from the impact of higher interest rates, and enhance profitability.

‘We expect to reinvest proceeds from the AFS sale into a more asset-sensitive, short-term AFS Portfolio. To further strengthen balance sheet liquidity, we also plan to increase our term borrowings from $15 billion to $30 billion and hedge these borrowings to mitigate higher funding costs in the future. We expect these actions to better support earnings in a higher-for-longer rate environment, providing the flexibility to support our business, including funding loans, while delivering improved returns for shareholders.

‘While we will realize a one-time, post-tax earnings loss of approximately US$1.8 billion in connection with the sale, we expect the reinvestment of the proceeds to be immediately accretive to net interest income (NII) and net interest margin (NIM), resulting in a short payback period of approximately three years. As a result of these actions, we expect an approximately $450 million post-tax improvement in annualized NII.’

SVB shares recorded its largest intraday loss that day, falling more than 60%:

|

|

| Source: WSJ |

The end was near.

SVB’s duration mismatch

What’s intriguing about Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse is the lack of bad assets to blame. Unlike the failures of 2008 triggered by souring loans, SVB was undone by poor risk management.

As we’ve mentioned, SVB saw a huge influx of client deposits during the pandemic. It decided to invest the bulk of it into long-term government-backed securities at a low, fixed rate.

That seems sensible and safe.

What could go wrong with parking client cash in ultra-safe government-backed securities?

Duration risk and maturity mismatch.

SVB chose to invest in longer-term securities that had more than 10 years to maturity at a time when these were yielding less than 2%.

This left SVB open to interest rate risk.

When the US Fed began the fastest rate hike cycle in history, Silicon Valley Bank’s longer-term assets began to lose value with each passing interest rate increase.

That led to problems on multiple fronts.

FT’s Robert Armstrong explained:

‘The yield on SVB’s assets is anchored by the level of long-term government bonds bought when rates were low; meanwhile, its cost of funding is rising fast. In the fourth quarter, its cost of deposits rose 2.33 per cent, from 0.14 per cent in the final quarter of 2021. But deposit costs will keep rising as more deposits roll over, even in the absence of further rate increases.

‘That’s why SVB sold $21bn of bonds. It needed to reinvest those funds in shorter-duration securities, to increase yield and to make its balance sheet more flexible in the face of any further rate increases. And then it needed to raise capital to replace the losses made in those sales (if you buy a bond when rates are low, and sell it when rates are high, you take a loss).’

SVB borrowed short to lend long. That’s any bank’s motto. In SVB’s case, however, the duration gap between its assets and liabilities left it more open to interest rate risk.

Deposits to a bank are almost like overnight loans — customers can call on these deposits at any time.

But a bank’s assets are much less liquid. In SVB’s case, most of its assets were longer-dated securities carrying unrealised losses.

That left it even more vulnerable to a bank run.

Held to maturity and other accounting magic

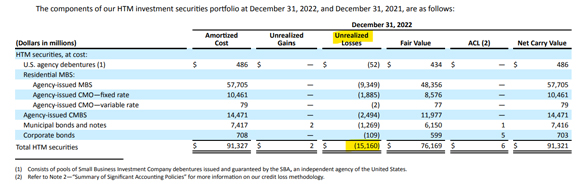

While SVB incurred a real loss when it sold a portion of its longer-dated securities, it was able to carry unrealised losses due to classifying these securities as ‘held to maturity’.

Banks don’t have to incur losses on bond portfolios if they hold on to them until maturity. However, if the bank suffers a liquidity crunch — like a bank run — those losses suddenly become very real.

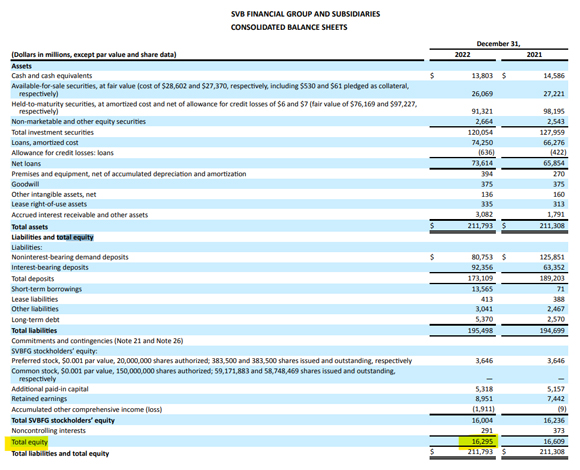

Silicon Valley Bank was carrying unrealised losses north of US$15 billion at the end of 2022.

|

|

| Source: SVB SEC filings |

That put it in a precarious position, given its total equity — the cushion between SVB’s assets and liabilities — was US$16.3 billion.

|

|

| Source: SVB SEC filings |

Silicon Valley Bank’s fire sale on 8 March and the subsequent share price drop crystallised all these worries…and led to a depositor panic as clients withdrew their deposits.

The homogenous nature of SVB’s clientele did not help as venture capitalists took to Twitter and fanned the panic.

At one stage, depositors attempted to withdraw US$42 billion from the bank.

That was more than the bank could handle, and on Friday, the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation took control of the bank.

It was over. Silicon Valley Bank had collapsed.

Silicon Valley Bank collapse fallout

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank precipitated the collapse of yet another bank. Over the weekend, US state regulators closed Signature Bank.

Signature Bank became the third-largest failure in US banking history, two days after the country’s second-largest such failure.

Signature was heavily involved with the crypto community and held more than US$110 billion in assets.

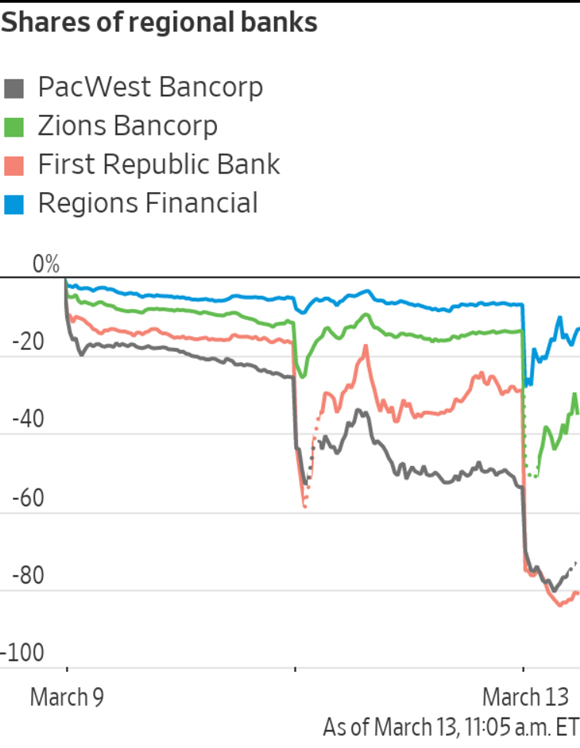

Judging by the market’s reaction, we may get another bank collapse this week.

Overnight, shares of US regional banks cratered, despite the intervention of the US Government and Fed.

First Republic Bank, at one stage, fell nearly 80% before closing 60% down overnight:

|

|

| Source: WSJ |

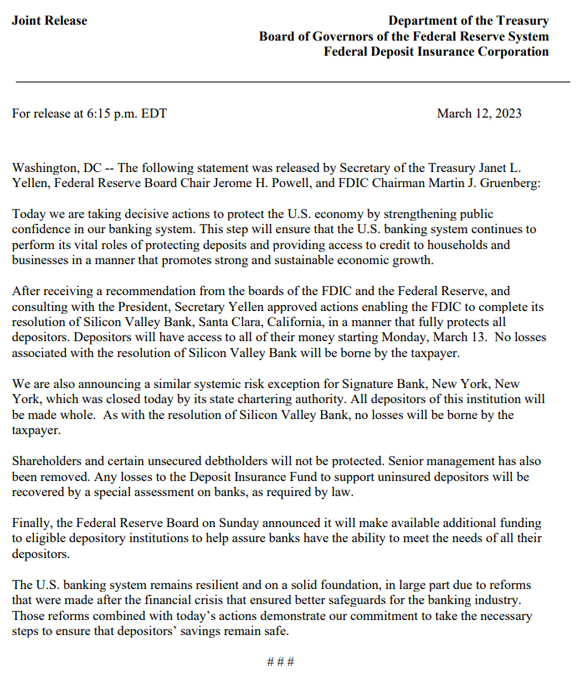

The intervention

SVB’s failure threatened to have pernicious ripple effects.

The vast majority of the bank’s clients were businesses whose deposits exceeded the deposit insurance cap.

If these businesses could not recover their deposits, they will not be able to meet payroll.

The collapse threatened much of the start-up economy.

But the government came to the rescue, making sure to say this was not a taxpayer-funded bailout.

The US Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC announced that all depositors of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank will be fully protected. Shareholders and certain unsecured debtholders will not.

|

|

| Source: US Treasury |

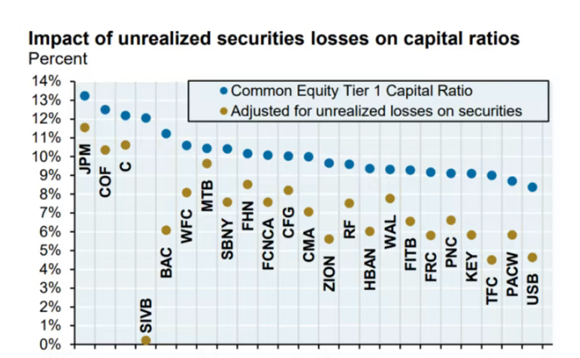

Will SVB lead to contagion?

Is the collapse of SVB emblematic of something far greater and scarier?

Is SVB a prologue to disaster?

That’s the question the markets will be dealing with for the foreseeable future.

Robert Armstrong, for one, thinks the contagion thesis is overcooked:

‘Why won’t most other banks face a similar crisis? First, few other banks have as high a proportion of business deposits as SVB, so their funding costs won’t rise as quickly. At Fifth Third, a typical regional bank, deposit costs only hit 1.05 per cent in the fourth quarter. At gigantic Bank of America, the figure was 0.96 per cent.

‘Second, few other banks have as much of their assets locked up in fixed-rate securities as SVB, rather than in floating-rate loans. Securities are 56 per cent of SVB’s assets. At Fifth Third, the figure is 25 per cent; at Bank of America, it is 28 per cent. That is still a lot of bonds, held on bank balance sheets at below their market value. The bonds’ low yields will be a drag on profits. This is no surprise and no secret, though, and banks with more balanced businesses than SVB should be able to work through it.’

|

|

| Source: JPMorgan |

Will Silicon Valley Bank fiasco lead to Fed pivot?

Another question is whether the fears around the US banking system will lead the US Fed to reverse course on its interest rate policy.

The market is already revising its terminal rate bets.

Traders are now pricing in a terminal Fed funds rate of ~5%.

It was 5.7% just on Thursday!

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

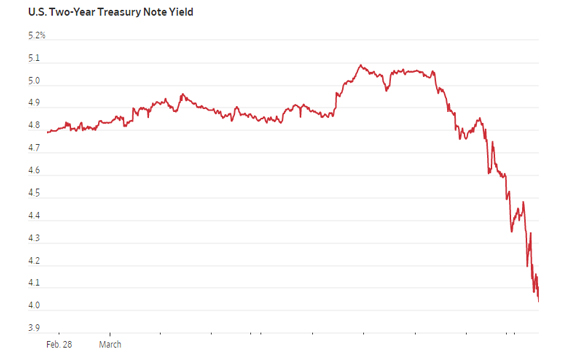

Overnight, the yield on the two-year US Treasury note fell to 4.030%, the biggest one-day and three-day declines since the stock market crash in October 1987.

|

|

| Source: WSJ |

The next few weeks ahead will be very volatile.

Be prepared.

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning