The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is the world’s leading exponent of money printing and blatant market price intervention.

In a never-ending effort to stimulate economic activity, all manner of artificial mechanisms has been (dreamt up, and) employed by Japan’s central bank and elected officials.

Remember, the late PM Shinzo Abe’s much hyped ‘Three Arrows’?

- Monetary easing from the Bank of Japan

- Fiscal stimulus through Government spending

- Structural reforms

Firing the second arrow was highly conditional upon the launch of the first arrow.

The BoJ went into quantitative easing (QE) overdrive AND, for good measure, in February 2016, pushed borrowing rates on Government debt into the negative.

In a concerted attempt to contain the Government’s debt servicing cost, yield curve control (YCC) was introduced by the BoJ in September 2016.

For almost seven years, the BoJ has been actively manipulating the interest rate pricing on Japan’s 10-year Government bond.

Meddling with market forces can work for a period of time, but not indefinitely…which is why Communism failed.

Markets — in the end — always win.

BoJ gives a little

Late last week (28 July 2023), the newly appointed Bank of Japan Governor announced a ‘mea culpa’ of sorts, on yield curve control….

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

To quote from the article (emphasis added):

‘The Bank of Japan heralded the start of a slow shift away from decades of massive monetary stimulus on Friday, allowing the country’s interest rates to rise more freely in line with increasing inflation and economic growth.

‘In what some analysts said could be a seismic shift for global financial markets, the BOJ made its bond yield control policy more flexible and loosened its defence of a long-term interest rate cap.’

What prompted the change in policy direction?

‘BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda brushed aside the view that the move was a step towards policy normalisation, instead describing it as a pre-emptive move against the risk of too-high inflation.

‘But he also said the bank could tweak policy further if the likelihood of sustainably hitting its 2% inflation target heightens, underscoring the sharper focus on price pressures.’

Governor Ueda’s public assurance that this modest relaxation in YCC is not a declaration of ‘relinquishing control on interest rates to market forces’ — it was intended to calm investor nerves.

Why would he do this?

We’ll get to that shortly.

But first, let’s look at the caveat of ‘the bank could tweak policy further if the likelihood of sustainably hitting its 2% inflation target heightens.’

The good oil on Japan’s inflation

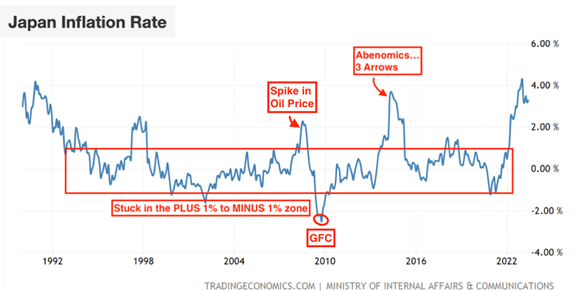

Over the past 30 years, Japan’s inflation rate has, for the most part, remained in the MINUS 1% to PLUS 1% range.

Prior to the current spike up to 4%, the two previous inflation surges were due to one-off impacts…the 2007 oil price spike and an adrenalin shot from Abe’s arrows.

Both wore off and Japan’s inflation went back into its longer-term box…much the same as it did (on the downside) after the GFC.

|

|

| Source: Trading Economics |

You may recall in 2007 that the oil price rocketed to US$140/barrel.

|

|

| Source: Trading Economics |

Japan is highly dependent on imported oil for its energy needs.

Which makes the Land of the Rising Sun vulnerable to oil price ‘shocks’.

As reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA)…

‘Oil remains the most significant energy source in Japan, accounting for about 40% of the country’s total energy supply…

‘Having no notable domestic production, Japan is heavily dependent on crude oil imports, with between 80%–90% coming from the Middle East region.’

Therefore, it’s no coincidence Japan’s inflation rate tracked higher with the oil price in 2022.

In 2023, commodity prices have taken a breather. However, in recent weeks there’s been an uptick in the cost of crude.

Could a resumption in higher fossil fuel pricing be the reason why Governor Ueda is hedging his bets on whether a further tweak in YCC policy might be required?

Another wave of higher oil prices was the topic of discussion in the June 2023 issue of The Gowdie Advisory.

To quote…

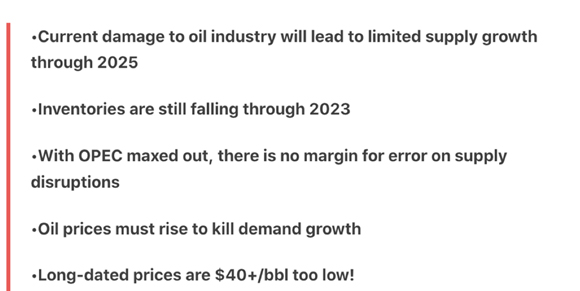

‘What about an oil shock?

‘Perhaps one is coming in the second half of 2023.

‘Global advisory group, Raymond James, recently published this report…

|

|

| Source: Raymond James |

‘In summary, the reasons for this outlook are…

|

|

| Source: Raymond James |

‘What would a spike of US$40 in oil do to the economy?

‘We know the answer to that question by what happened in the 1970’s and late 1980s.

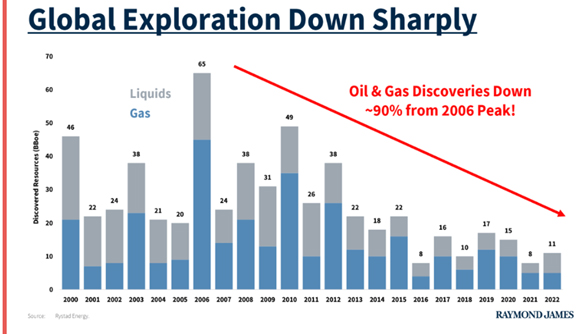

‘In support of their outlook, the research team at Raymond James provided these charts.

‘New sources of (oil and gas) supply are in decline…

|

|

| Source: Raymond James |

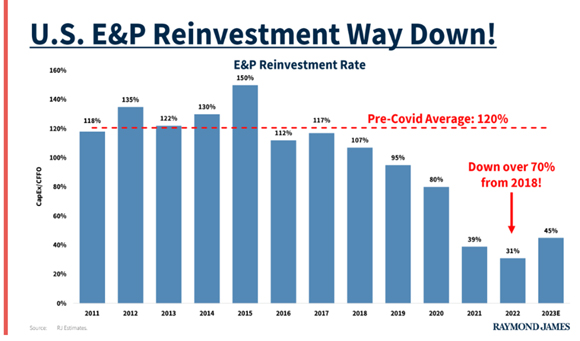

‘Reinvestment in E&P (exploration and production) has also been headed in the wrong direction…

|

|

| Source: Raymond James |

‘Economics 101 is all about supply verses demand.

‘Limited supply verses increased demand equals higher prices.’

If we are entering an unsettling period of rolling ‘oil shocks’ (much like what happened in the 1970s), containing the impact higher energy prices has on inflation, means the repeated use of that blunt instrument — higher rates — is all but assured.

The most least discussed risk in the financial press

At present, yield curve control requires the BoJ to spend tens of billions of dollars EVERY SINGLE BUSINESS DAY of EVERY WEEK of EVERY MONTH in EVERY YEAR. The annual cost is beyond HUGE.

In a world of sustainably higher rates, marshalling the financial effort to combat global bond market pressures, could see the Bank of Japan throw its hands up in the air…abandoning its long-running experiment in interest rate suppression.

And that’s where it gets (pardon the pun) interesting and why investor anxiety levels will go up even higher than interest rates.

Would that result in Japanese investors making a wholesale retreat (selling out) from foreign markets to re-invest their repatriated capital in the higher-yielding JGBs (Japan Government Bonds)?

The 25 January 2023 issue of The Gowdie Advisory, under the heading of, ‘Is there another Lehman Moment out there?’ included this extract…

‘Why we should be looking at Japan. To quote (emphasis added):

‘I think Japan is perhaps the most important risk in the world, not least because it is among the least discussed risks, certainly in the Western press.’

Who said it and in what context? That’s the subject of part two in next week’s The Daily Reckoning Australia.

Until then.

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia