As I write this early on Friday morning, the share price of US regional bank, PacWest Bancorp, is down around 50%.

By the time you read this, it may be in receivership. That would make it four US banks gone bust in the space of a few months.

A day earlier, Fed boss Jay Powell put on one of the great bureaucratic comedic performances of our time, with his press conference opening monologue:

‘Before discussing today’s meeting, let me comment briefly on recent developments in the banking sector. Conditions in that sector have broadly improved since early March, and the U.S banking system is sound and resilient. We will continue to monitor conditions in this sector. We are committed to learning the right lessons from this episode and will work to prevent events like these from happening again.’

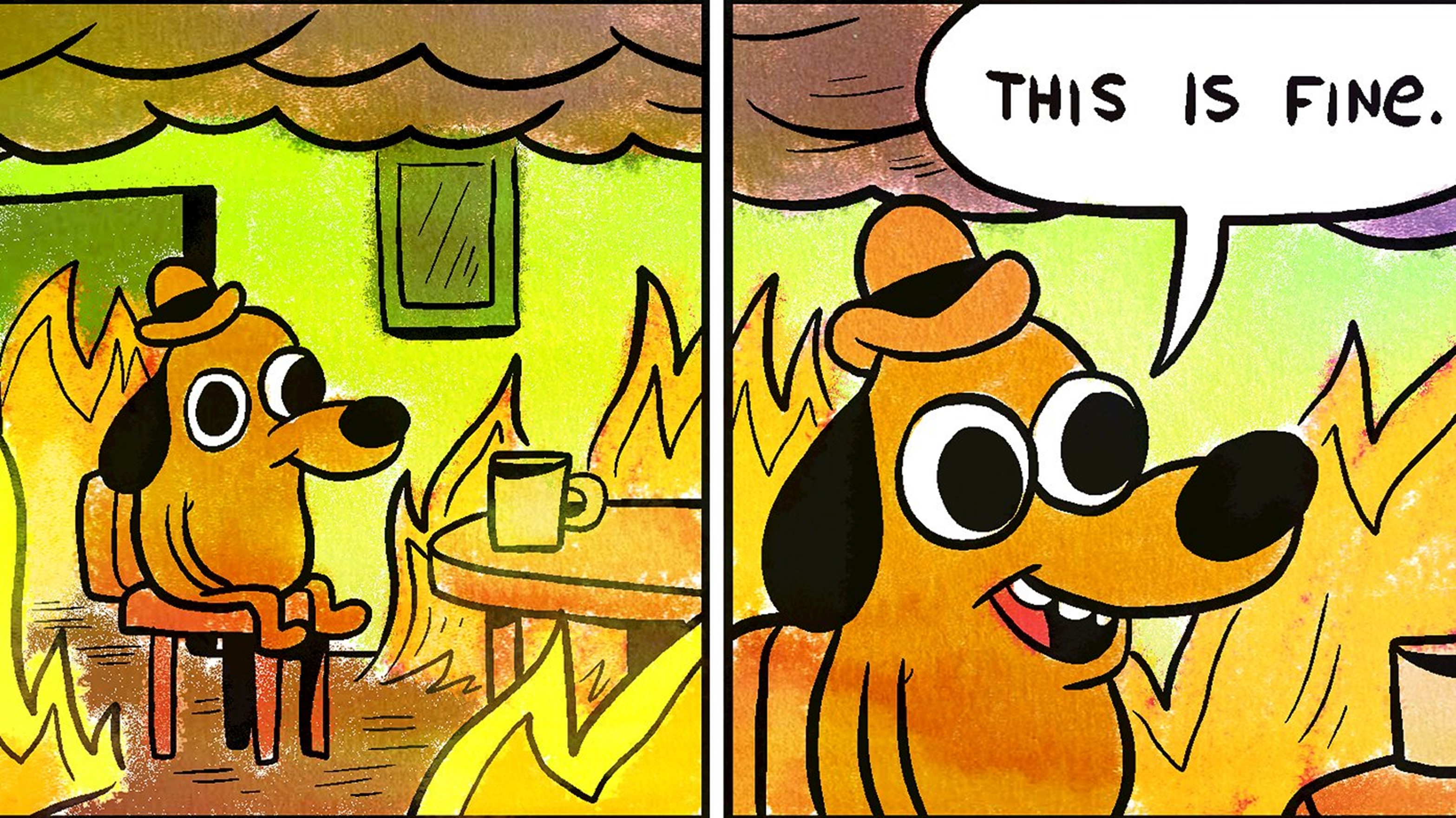

This calls for a classic meme:

Is the US banking system burning down while the Fed sips coffee and says everything is fine?

I think it’s a pretty good metaphor. Here’s why…

Back to front bank run

Usually, when banks get into trouble, it’s because their loans (the asset side of the balance sheet) sour. These assets come under scrutiny and lenders (the liability side of the balance sheet) start to get nervous.

The difference between assets and liabilities is bank equity. If a bank is leveraged 20 times, a 5% fall in the value of the assets will wipe out the equity holders.

So banks are pretty fragile. But a well managed bank can make very good profits from this leverage. Just look at Australia’s ‘big four’.

But in this situation, the Fed has engineered a completely different panic. By raising rates so far and so fast, they have sparked a run on the regional banks. But they’re not running from bad assets. They’re running to higher yielding assets.

People aren’t concerned about the banks’ asset quality. They’ve just woken up to the fact that their deposit rates are still living in 2021.

Why hang around for sub-1% when you can get 5% in a money market fund?

So the liability side of a banks balance sheet is walking/running out the door. When deposit flight becomes extreme, banks are forced to sell their assets. But because interest rates have increased so much in the space of one year, the assets (loan or securities) have fallen in value. The bank, therefore, sell at a loss.

The equity holders must absorb this loss. And in a highly levered bank, losses can wipe out equity holders pretty quickly.

For example, PacWest Bancorp, the latest bank in its death throes, had US$2.77 billion in shareholder equity supporting $44.3 billion in assets as at 31 March. That’s 16 times levered.

So a 6.25% decline in assets blows up the equity holders. And as everyone knows, thanks to soaring rates this year, US banks have hefty mark-to-market losses on their balance sheets.

This isn’t a problem, until it’s a problem. And depositors looking for a better deal is a problem.

Why can’t banks just raise their deposit rates to stop capital walking out the door?

If they did, it would destroy their profits.

They really are between a rock and a hard place.

Can’t they just borrow from the Fed, via the Bank Term Funding Program?

They can, but that comes at a cost of 4.7%. Again, that’s not a solution.

When you flip the switch on the era of cheap money, and cause the cost of capital to soar in the space of 12 months, its going to lead to casualties.

But according to the Fed, the banking system is ‘sound and resilient’. So they hiked rates again, making money market rates more attractive and encouraging more deposit flight.

Look, JP Morgan and Wells Fargo are sound and resilient. But they’re not out there lending to small businesses across the US.

This kneecapping of the smaller banks by the Fed will certainly have flow on effects. They will curtail lending. They just don’t have the balance sheet capacity to lend right now. Credit creation will slow, or even contract, unemployment will rise, and the economy will go into recession.

The inflation fight is over

Meanwhile, the Fed is still fighting inflation. LOL.

Someone should tell Jay that since the June 2022 peak, oil prices are down nearly 50% (and an absolute bargain at these levels IMO).

Also, someone should remind him that the US inflation rate hit 5.6% in July 2008. Six months later it was all about deflation.

This is not 2008 again, to be clear.

Rather, I point this out to show you that inflation is a badly lagging indicator. The Fed is fighting a number that is no longer there.

The 10-year inflation breakeven rate – a measure of the market’s long term inflation expectations – peaked for 2023 at 2.52% on 3 March. Then came the regional banking crisis. The breakeven rate is now 2.19%. That’s a 33 basis point decline in two months!

The market is saying – correctly – that the Fed’s monetary policy is tight, and inflation is falling.

The upshot of this is that the data should start to come in noticeably weaker in the coming months. That will probably be enough to have the Fed on hold.

How long it takes to start cutting again will depend on how bad the data is.

Rate cuts aren’t bullish!

But remember this wire I wrote back in early March? In it, I explained that the start of a Fed rate cutting cycle is not always bullish. In the 2001-02 rate cutting cycle (which saw the Fed funds rate fall from 6.5% to 1.25%) the S&P500 fell 40%.

It was a similar situation in 2008/09. The Fed started cutting rates in September 2007, just as the market peaked. It cut throughout 2008 to 0%. Meanwhile, the S&P500 fell 50%, from top to bottom.

No two markets are the same. So I’m not saying the parallels will be the same this time around.

But I am saying that the Fed cutting rates will not be immediately bullish for stocks. It will be a sign of a sharply deteriorating US economy.

Has the market priced any of this in?

Yes and no. The major US indices are distorted by the tech giants. Capital is hiding in these modern day citadels.

But under the surface its more nuanced. For example, in Australia the Small Ordinaries index is now showing the best relative value versus the ASX20 (the twenty largest stocks on the ASX) in years.

As you can see in the chart below, the last time small caps were this cheap relative to the top 20 was during the 2020 panic, and before that, in 2017.

Indeed, the small caps have outperformed strongly during this more recent sell-off. It could be the start of a more persistent move.

So paradoxically, it might be time to look at the smaller end of the market for value as we head into what looks like a turbulent second half of the year.

Regards,

Greg Canavan

For Money Morning