Castles are no place for sick people. Not in the winter. The stone walls and rattlely windows make it impossible to heat properly. There are always mould spores in the cool air. And drafty hallways lead to rooms warmed only by open fires. You spend all day in front of the fireplace…feeding in logs.

Here in France, we live in a big ramshackle chateau far from the chic precincts of Paris. When people hear that you live in a chateau, they get the wrong idea. They think you must be rich. But chateaux in France are a dime a dozen…and everybody sees them as a sign, not that you are rich…but that you are stupid.

They are expensive to keep up…impractical…and uncomfortable. They drain away savings fast. Energy ebbs away too, as you struggle to keep up with repairs.

‘When I came to France’, says an English friend in a similar situation, ‘I was in good shape and the chateau was broken down. Now, I have fixed up the place…but I am broken down.’

So the rich move on — to ski chalets in the alps…to apartments on the Avenue Foch…or villas on the cote d’Azur.

But we’re still here. This is our home, such as it is…and like an old pair of boots…or an old spouse…we’ll stick with it until one of us wears out.

|

|

|

Source: The Bonner Chateau…impractical, uncomfortable…home. |

Meanwhile, comes the news from the New World:

‘Eastern US faces bomb cyclone of snow and wind’, says a headline.

We used to face ‘snowstorms’. A ‘bomb cyclone’ sounds much scarier. Surely, it is caused by ‘climate change’. And surely, we are all doomed.

Keeping people in a state of alarm seems to be a good strategy for the major media — and the government itself. They seem to want to keep you glued to the news cycle…and ready to follow orders.

That’s part of the reason the Fed can no longer tolerate a normal market correction. Or normal interest rates. Now, they’re like normal flu seasons…or a normal recession — the media treats them like the end of the world. Something must be done!

The media creates the demand…the government rushes to fill it with the deciders demanding a new vaccine at ‘warp speed’…or a trillion-dollar budget boost immediately, or else ‘we may not have an economy on Monday’ (as Ben Bernanke, former Fed head, put it on 18 September 2008).

How to Survive Australia’s Biggest Recession in 90 Years. Download your free report and learn more.

Back to the Future

This week, we’ve been trying to peek into the future. We take it for granted that we will be surprised. After all, if the future were like the past, what would be the point of having it? We’ve already lived it.

So what will be the Big Frightening Headlines of the months ahead?

How about a stock market crash? Followed by another multitrillion-dollar rescue program?

The likelihood is hard to gauge. But it is not negligible. Commentators are telling us that there is ‘plenty of liquidity’, so that even if inflation increases and the Fed backs off from its money pumping, stock prices are likely to hold steady or rise.

That seems possible. On paper at least, there’s ‘cash’ everywhere — in the game and on the sidelines. But cash is sometimes bold…and sometimes fearful. It doesn’t necessarily want to go into a stock market at an all-time high…or stay there when prices fall.

The investment geniuses on TV tell you not to worry. We’ve had three major sell-offs so far this century, they say. Each time, you would have been better off staying put, rather than selling out.

And yes, we could relive any one of those first 21 years of the 21st century, but where would be the surprise in that?

|

|

|

Source: TheChartStore.com |

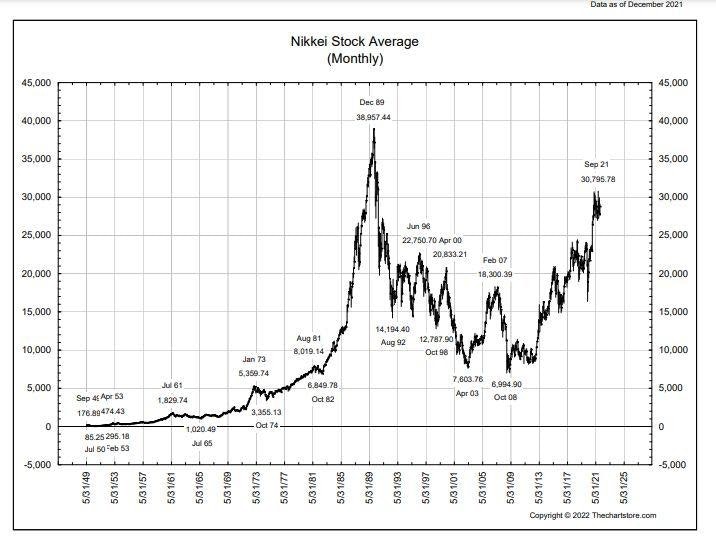

A real crash and bear market — such as the one in Japan beginning in 1989 — that would be a whole ‘nuther thing. Something people don’t expect. Stocks lost 82% of their value over the next 20 years…and still haven’t recovered 32 years later.

And the government’s liquidity didn’t help. It didn’t stop the Japanese stock crash…and it didn’t bring about a stock market recovery either. The Bank of Japan expanded its balance sheet (via ‘printing press’ money) by approximately 1,300% since 1989. Government debt went from less than 70% of GDP in 1989 to more than 250% today.

The interesting thing about ‘liquidity’…compared to cold, hard cash…is that it tends to disappear just when you need it. Stocks, for example, are easily liquified. But in a matter of hours…or days…the amount of available liquidity can go not just to zero….but below…to negative liquidity. You bought a stock on margin. The stock goes down. No margin left…instead, you get a ‘margin call’. You have to find some liquidity elsewhere or your positions get liquidated.

Margin debt — money borrowed against the value of stocks to buy more stocks — increased by more than 40% between October 2020 and October 2021. By the end of October 2021, it had reached US$935 billion — an all-time high. It declined to US$918 billion in November. Still high. But given last week’s action in the Nasdaq, you wonder if the margin calls have already begun.

Also, as investors become convinced that the best place for their money is in the stock market, they tend to leave it there — and borrow against it, rather than liquidate it. So when stocks go down it drains money from other parts of the economy as well.

Imagine a whole society calling up banks…and turning up the seat cushions — looking for liquidity. They will need to refinance overpriced houses…to roll over record business debts (many zombie businesses will soon be desperate)…and to salvage underwater investments.

In short, when prices are falling, cash goes into hiding.

A mean reversion

In these pages, for example, we calculated that the FANGMAN stocks alone could hold as much as US$8 trillion in vanishing liquidity.

But wait…a TV financial commentator tells us we have a whole new source of ‘liquidity’ — cryptos. They are certainly ‘liquid’ forms of wealth, readily exchanged for other cryptos…and even dollars. That market is said to be worth nearly US$3 trillion, ‘that’s $3 trillion dollars of purchasing power that didn’t exist before’, he beamed.

But it’s also US$3 trillion that could evaporate as easily…and much faster…than it accumulated. Ex nihilo nihil fit. So the nili might go right back to the nihilo whence it came.

In fact, the total market cap of cryptos hit that US$3 trillion peak in November of last year. As of Thursday, it was US$1.99 trillion, according to coinmarketcap.com. The big culprit is Bitcoin [BTC] — the largest crypto by ‘market cap’ — which has fallen from US$69,000 at its high to around US$41,000 (a respectable correction of 40%).

Taken as a whole, if the stock market were to go back to normal range, about US$20–30 trillion would go away. That’s based on the historic mean of Warren Buffett’s famous market cap-to-GDP indicator, which is 86%. In other words, with GDP around US$23.2 trillion today, stocks would be worth around US$29 trillion. The total market cap of the Wilshire 5,000 — the broadest measure of US stocks — hit US$48.7 trillion earlier this week.

You do the maths. Or we’ll do it for you. Stocks would lose around US$28.8 trillion if they declined from 211% of GDP to 86% of GDP. Give or take a couple of trillion, given how markets tend to overcorrect.

How much liquidity would you have then?

Not much. And that would be a big surprise to everyone.

Regards,

|

Bill Bonner,

For The Daily Reckoning Australia

PS: It’s not just the magnitude of the bear market that matters. It’s the duration of time. You never get the time back.

The last bear market (defined as a fall of 20% or more from an all-time high) was short and sweet. The S&P fell more than 30% during 23 trading days in February and March of 2020. But thanks to the Fed, the index is up 109% since then. Holding paid.

The bear market in 1929 saw stocks fall 86%, peak-to-trough, and lasted 34 months. The 1987 crash saw stocks lose 34% in three months. The S&P 500 lost 49% over 31 months after the dotcom crash in 2000, it was 78%, peak-to-trough, for the Nasdaq. It was a 57% ‘drawdown’ for the S&P over 17 months after the housing bubble popped in 2007.

Our asset allocation strategy, which Dan Denning tells me he’s updating for early next month, is based on the next crash being bigger (and taking a lot longer to recover from) than recent crashes. Why?

It’s a crash in everything. A failure of the Fed’s QE era. Perhaps even a failure of the US dollar itself. Do you have a plan for that?