After some conversations with Money Morning Editor Ryan Dinse, he’s asked me to bring some of my work to the fore for our readers.

In the new year, we will bring a tech-focused concept that will involve deep dives and research to highlight the latest developments in tech that we think will become the future.

More to come, so watch this space.

For now, I thought it might be worth examining the weakening Aussie dollar, considering that any foreign investment carries currency risks.

Understanding this should be beneficial for those of us who hope to invest more in the burgeoning tech sector or any US sector that looks ripe for opportunity.

Australia’s Dutch disease

At the beginning of the year, the Aussie dollar bought 71 US cents. That’s now down to just 63 US cents and falling.

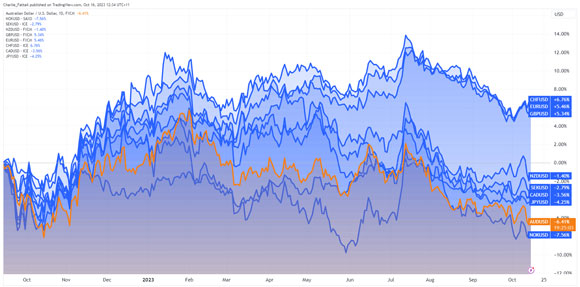

Here is how the Australian dollar has performed against the US dollar compared to other G10 countries in the past 12 months.

|

|

| Source: TradingView (AUD in Orange) |

As a minor global player, Australia struggles to control its dollar as pricing pressures from iron ore, coal, gas, and wheat coerce it, but how did we get here?

Australia’s past success in its materials and energy sectors shifted the AUD from the 15th most traded currency in the 1980s to the fifth by the late 2000s.

The incredible expansion of these exports also led to a rapid appreciation of the AUD. This made the non-mining sector’s exports less competitive and led to a decline in other parts of the economy.

This economic malaise is known as the Dutch disease.

In 2023, Australia dropped to 93rd out of 133 countries in the Atlas of Economic Complexity rankings, down 38 places from our position in 1995 and landing just behind Uganda.

The falling complexity has meant that the AUD is now globally seen as simply a proxy for commodity prices.

Fall of the commodity currency

Australia has benefited from the relationship between AUD and the broader commodity market in the past.

The significant growth of China, along with their demand for coal and iron ore, has helped us and our dollar.

China is Australia’s largest two-way trading partner, accounting for almost a third of Australia’s global exports. That’s about as large as the next four partners combined.

Much of this trade relied on China’s surging manufacturing and a growing property sector bubble.

The property sector in China began to wobble in 2020 but has now well and truly fallen off the wall.

New annual housing starts in China are down 57%, and many analysts predict a longer-term structural decline.

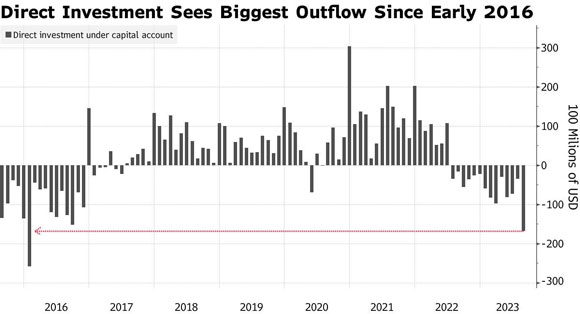

China is struggling to replace that key engine of growth, and foreign capital is flowing out of the country.

|

|

| Source: Bloomberg |

With the property market in decline, commodity demand has weakened along with our dollar.

Iron ore prices are down 50% from their highs in mid-2021, around when China’s extreme lockdowns brought its economy to a shuddering halt.

A global slowdown has also weakened consumption in the broader commodity markets.

Australia’s earnings from commodity exports are expected to be $400 billion in FY24, down from $467 billion in FY22.

In its latest report, Australia’s Department of Industry predicts further declines, with exports totalling only $352 billion in FY25.

The comeback kid

When the pandemic hit— everyone, including Australia — slashed interest rates to zero to stimulate the economy, and central banks ignored history and assumed that this was the ‘new norm’.

Central banks and monetary policy think tanks said in a collective chorus:

‘The long decline in safe interest rates stems from deep underlying factors that do not appear likely to reverse anytime soon,’ echoed former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard as late as early 2022.

After a wave of unbridled stimulus spending and the invasion of Ukraine, Australian inflation peaked at 7.8% in December 2022, a 40-year high.

In the battle against inflation, we have entered an era of ‘higher interest rates for longer’. This once again places Australia at the mercy of larger economies.

The US economy has shown surprising resilience during this period, with robust employment and a positive outlook across its manufacturing.

This strength has been underpinned by hotter-than-expected US consumer inflation data in recent months, reinforcing the view that the Federal Reserve will keep interest rates higher for longer and could even raise rates.

The chance of higher rates caused people to sell US Treasuries, and as the price of Treasuries falls, their yield rises. Higher yields then attract currency inflows, pushing the USD even higher.

By contrast, the latest IMF assessment of the Australian economy predicts our GDP growth to be a mere 1.8% and unemployment to rise to 4.3% in 2024.

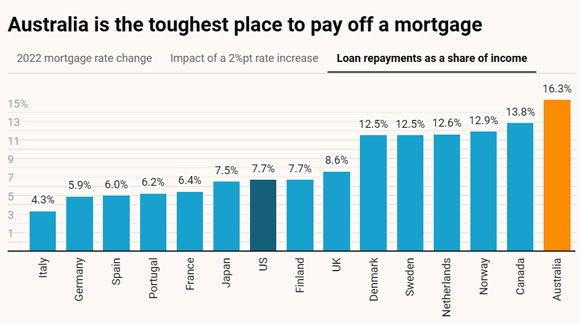

The report also showed that Australians spent the highest share of income in the developed world on loan repayments.

|

|

| Source: The Guardian-IMF |

This weakness creates a cautious stance in the RBA, acknowledging the economic and political risks associated with increasing rates beyond current levels.

As a consequence the RBA has raised interest rates more slowly than the US Federal Reserve and has betrayed a more dovish tone than its Yankee cousin.

This has made Australian assets less attractive to foreign investors who are more likely to invest in countries with higher interest rates, as this provides a higher return on their investment.

The problem is also exacerbated by geo-political tensions, such as the Middle East conflict, as investors seek safe havens like the greenback that further degrade our dollar.

Implications of our weak dollar

The knock-on effect of a weaker Australian dollar can be complex in a higher interest rate environment.

On a positive note, exports become more competitive and could help stimulate the economy as trade picks up with our partners, but the consequences could be painful.

Import costs have surged, affecting everything from consumer goods to large-scale industrial equipment.

As a result, businesses face increased expenses, hindering investment and economic growth. This is painful when we already have investment near a 30-year low as a proportion of GDP.

Moreover, the weakened currency has led to imported inflation, impacting households’ purchasing power and eroding their standard of living.

The problem from here lies in the RBA’s ability to fix the problem meaningfully.

If they raise interest rates to curb inflation, households will remain crushed by their massive debts, and anaemic investment could worsen — potentially pushing us into recession.

If they instead cut interest rates, even more capital would flow to other currencies, high inflation would persist and Australians would see their purchasing power and savings continue to decline.

Predicting where the Australian Dollar goes from here is a tricky one. China is considering stimulus, but so far, nothing has been substantive to the scale of the problem.

Simply put, it’s ‘stimulus or bust’ for our major trading partner as it slowly attempts to restructure its debts.

For the US, the strong greenback will likely remain a headache for global trade until heat comes out of its economy.

The US public is still running down its US$2 trillion-plus pandemic-era savings. This consumer spending is around two-thirds of America’s total economic activity.

Once savings run down, things could begin to slow.

For now, the greenback’s dominance is here to stay.

Regards,

|

Charlie Ormond,

For Money Morning