THIS WEEK: Look out for NOT ZERO, a controversial new Fat Tail Investment Research report that reveals why the goal of going carbon neutral by 2050 cannot possibly happen. Learn the shocking truth about the massive shortfalls of key commodities needed for the transition…and discover why some of the world’s wealthiest investors have been buying oil and gas stocks for over a year now — despite what their PR says. In NOT ZERO, you’ll get our take on what it all means…PLUS you’ll hear about a smart, ahead-of-the-curve way to play what stands to be the biggest energy U-turn in history…

The Department of Industry, Science and Resources thinks Australia is ‘set to become a renewable energy superpower’.

Our ‘vast coastline’ and ‘clear skies’ are ideal for solar and wind.

These natural endowments mean Australia has the ‘second-highest potential for solar power production in the world’.

All this is great.

But how much of that potential should Australia realise? And how quickly?

Will it be worth it?

The ‘most important chart in the world’

Economist Noah Smith recently wrote a trending piece lamenting the state of the debate surrounding the energy transition.

For him, it is clear ‘solar and batteries are going to win, and our thinking needs to adjust accordingly’.

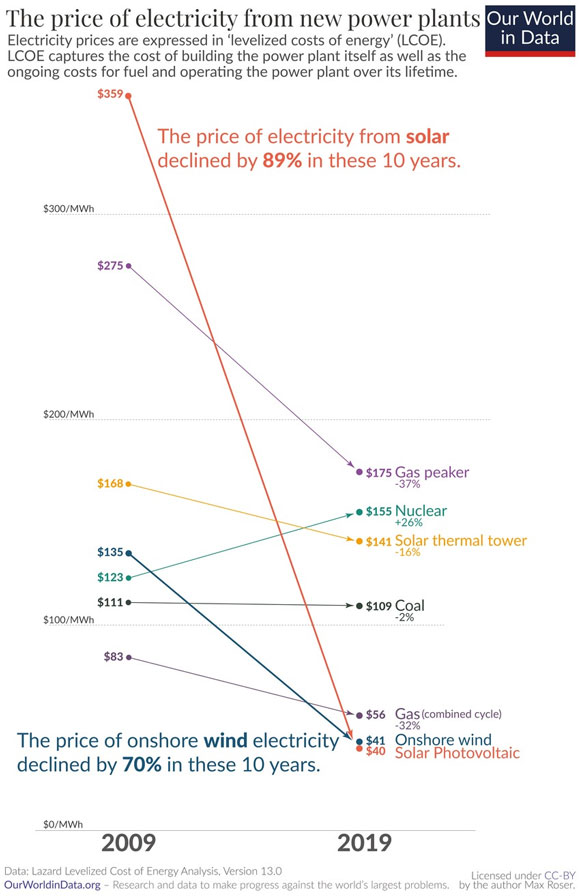

Smith then showed what ‘might be the most important chart in the world’.

It shows the price of electricity from new power sources, encompassing the building and ongoing costs.

|

|

|

Source: Our World in Data |

In just 10 years to 2019, the price of electricity from solar fell 89% while the price of onshore wind electricity fell 70%.

Our World in Data’s chart shows wind and solar are cheaper sources of electricity than gas and coal.

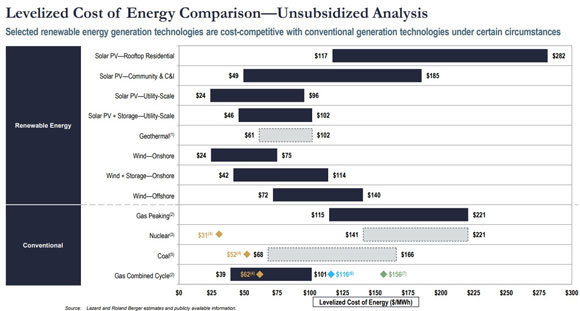

As Smith pointed out, as of 2023, even without subsidies, ‘solar power is cheaper than most other ways of generating electricity — even when you factor in energy storage’.

|

|

|

Source: Lazard |

Are solar and wind cheaper than fossil fuels?

Wait.

Didn’t I write last week that the costs of renewable energy may be understated?

Last week, our editorial director Greg Canavan — in his investigation of Australia’s energy transition and its costs — interviewed data scientist Aiden Morrison.

Morrison caused a stir in recent months by critiquing the CSIRO’s annual GenCost report that seeks to calculate the costs of different energy sources.

Since 2018, CSIRO’s GenCost found ‘wind and solar are the cheapest forms of newly built electricity generation’.

But Morrison took issue with some key assumptions relating to sunk costs.

The GenCost report treated the cost of rolling out renewable energy infrastructure up to 2030 as sunk.

That is, it did not include those costs when calculating how cheap it will be to build new renewable energy capacity from 2030 onwards.

Morrison wasn’t the first to raise this criticism.

In fact, the CSIRO addressed the same point in an appendix attached to its latest report, writing:

‘In GenCost we take the year 2030 and observe the combination of renewables and supporting technology that must be built for four levels of variable renewable energy (VRE) share — 60%, 70%, 80%, 90% — starting form a system that has already exceeded 50% VRE.

‘[A] concern is that the costs to achieve 30%, 40% and 50% should also be added to those four VRE share costs. From the discussion above it should be clear that this is not the case. Each specific VRE share has its own cost which reflects the last new entrant needed to reach that share reliably, which will be a combination of renewable generation capacity, storage capacity, peaking capacity, renewable energy zone transmission and other additional transmission capacity.’

CSIRO’s chief economist Paul Graham then defended the sunk cost assumption again two months ago, following coverage from The Australian’s Claire Lehmann.

Graham was upfront and unapologetic:

‘The report does not provide the cumulative cost of all investments up to 2030 because this is addressed in a separate project called the Integrated System Plan of which GenCost is one of many inputs. All existing generation, storage and transmission capacity up to 2030 is treated as sunk costs since they are not relevant to new-build costs in that year.’

So, we may not be able to rely on the GenCost report to argue about the cheapness of renewables before 2030.

But we can say that after 2030, any new renewable energy sources built, will be cheaper than any new traditional sources like coal and gas.

As The Guardian’s Graham Readfearn points out, the CSIRO’s approach to sunk costs wasn’t a secret and had its reasoning:

‘[The Australian’s] Lehmann and critics say treating these projects as “sunk costs” amounts to a “creative accounting method” and disguises the true cost of renewables.

‘But Lehmann doesn’t mention that the same GenCost report includes a long explanation of why this is done.

‘In short, a stakeholder in the year 2030 who wants to have an idea of the cost of building new renewable energy generation is not interested in investments that have already been made into the grid to integrate renewables.’

But what about current costs of renewable energy?

The Australian Energy Market Operator’s Integrated System Plan (ISP) claims that solar and wind energy, backed by storage, are the cheapest, especially when factoring Australia’s climate targets.

(Morrison, by the way, disputes some of the methodology used in the ISP.)

Finally, in a 2020 research bulletin, a team from the Reserve Bank summed up research on the costs of renewable energy sources.

The RBA team found the costs of wind and solar are falling ‘markedly’.

It confirmed CSIRO’s finding that building a new generation-only renewable plant is cheaper than building a new fossil fuel plant.

However, the case is ‘less clear’ when you incorporate storage costs.

Here’s the important snippet:

‘The costs of wind- and solar-generated electricity have decreased markedly over the past decade. While it is difficult to compare the cost of electricity generation from different sources, one common approach is to use the Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) measure. This represents the present value of the cost of building and operating a power plant over its assumed life. While renewable power plants have quite high fixed costs, their operating costs are very low owing to the zero cost of fuel (e.g. wind and sunlight). The LCOE for new renewable power plants has fallen significantly over the past decade and is estimated to be between 40 and 60 per cent of the cost of a new fossil fuel plant. This decline in the cost of new renewable generation has been driven by technological innovation as well as falling manufacturing and installation costs. On this measure, a new generation-only renewable plant is much cheaper to build than a new fossil fuel plant. However, if the cost of storage is incorporated, the case is less clear. For example, LCOE estimates for a new renewable plant with six hours of pumped hydroelectricity storage is around that of a new coal-fired plant. This estimate does not incorporate the risk that a new coal-fired power plant could encounter greenhouse gas emissions constraints over the course of its economic life. Once possible emission constraints are priced, the LCOE of a new coal-fired plant is higher than a new renewable generation plant with storage.’

Reckoning with the energy transition as Average Joes

The Australian’s Claire Lehmann and The Guardian’s Readfearn may have their differences, but both indirectly raised an important point in their coverage of Aiden Morrison’s critiques.

Lehmann said documents like CSIRO’s GenCost have received ‘surprisingly little scrutiny in the public arena’.

And Readfearn said the criticisms ‘centre on two reports that most Australians will not have heard of and even fewer will have spent any time reading.’

Both are probably right.

But is that a good thing?

The world is undergoing an energy transition and renewables will grab a larger share of our energy mix.

This will have consequences not just for policy wonks and authors of GenCost reports, but every Australian.

The future of energy is the future of our economy.

So maybe most Australians should hear about reports like GenCost and maybe more should spend time reading them.

And if enough hear and read these reports, the scrutiny of them will be constructive and illuminating.

Towards that end, our editorial director Greg Canavan is about to release a research report on Australia’s energy transition and its economic implications.

Stay tuned!

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning

PS: There’s another cracking interview Greg did recently that is a must-watch when it comes to the renewable energy debate…

| The Political Fallacy of Net Zero – Interview with Cory Bernardi |

In this video — a bonus episode of our podcast What’s Not Priced In — Greg talks to former Liberal Senator and founder of the Australian Conservative party, Cory Bernardi.

Cory has been a strident critic of the energy transition, seeing it as a global movement driven by Marxists, aided and abetted by what he calls a ‘spineless and leaderless’ political class.

In short, Cory says that the climate catastrophe scare tactics are more about fear and control, rather than anything else. It’s a compelling take on this controversial topic, and one that won’t see the light of day in mainstream media circles.

|

|