In my previous market outlook, I gave a contrarian prediction of the Cup Day rate rise that was off the mark. The RBA caved to pressure and hiked the cash rate 25 basis points to 4.35% — a 12-year high and the RBA’s 13th rate rise since May 2022.

Afterwards, the local dollar slid, and bond futures rallied as investors lowered the odds of a further rise in December.

‘It was a dovish hike…it’s not pointing to any immediate need for a follow-up,’ said Rob Thompson, rates strategist at RBC Capital Markets.

‘You’d think they’d have opened the door a bit more than this, but they are just trying to do as little as possible. The hurdle to hike is high.’

The urge to rise again came as the latest CPI rose 5.4% in the past 12 months. Still a long way off the RBA’s target range of 2–3%. It’s also well above the inflation rate of the US and Europe.

But one thing we do share with our trading partners is…massive amounts of debt.

The growing mountain

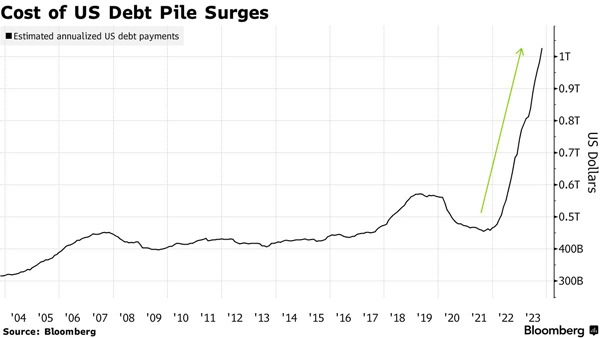

With high interest rates pushing up borrowing costs, government debt has come back under the spotlight.

Over 80% of the $10 trillion rise in global debt in the first half of 2023 came from developed economies. That totals $307 trillion, according to the Institute of International Finance.

Public debts that ballooned under the pandemic have risen — relative to GDP — to levels last seen in the Napoleonic wars.

For developing countries, the problem is amplified by the rising US Dollar and has reached a ‘silent debt crisis’, according to the World Bank.

For many countries, the cost to service their debt has reached multi-decade highs. Last week, the US debt interest payments passed $1 trillion a year.

These rising interest payments on the US debt create a vicious cycle. To attract new borrowers, yields on Treasury bonds must increase, which results in higher borrowing costs on the already-existing debt, which has now surpassed $33 trillion.

| |

| Source: Bloomberg |

Political wrangling over this mountain of debt has been fractious. Fitch Ratings infamously downgraded the US credit rating, saying:

‘The downgrade reflects concerns about the growth of the government debt and the ability of Congress and the administration to control spending.’

This high debt is also building in cash-strapped households. Delinquency rates are climbing here and in the US as pandemic-era savings dry up.

This is where Australia is especially vulnerable. In the past, when the Fed raised interest rates, US homeowners didn’t feel the brunt of the pain like Aussies; why?

Over 95% of American households are on long-term fixed-rate mortgages. These 30-year mortgages mean that the passthrough of interest rates to homeowners is minimal.

The total increase to all mortgage rates in the US is only 0.43%, as the higher interest rates only affect new homeowners. The opposite is true for Australia, where 84% of homeowners are on variable-rate loans, and fixed-rate periods last only a handful of years.

So, what does this mean for Australian homeowners?

Hey, big (mortgage) spender

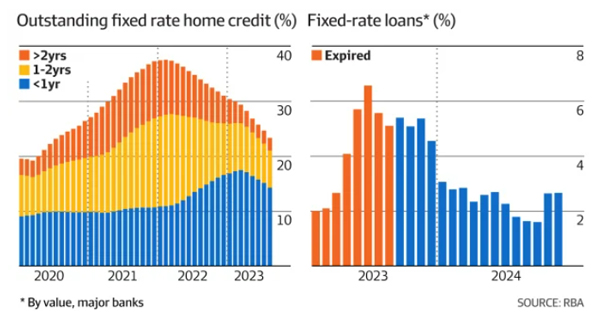

During the pandemic, the RBA offered commercial banks a term funding facility (TFF) of $188 billion for three years at near-zero percent rates.

The Big Four then gave Australians ultra-cheap fixed-rate loans to help the economy. As we sit halfway through the unwinding of these loans, the feared ‘mortgage cliff’ seems to have passed its peak.

| |

| Source: AFR-RBA |

But the sensitivity is still there. This is why the RBA lagged behind other Central Banks in its rate hike cycle. It’s also why some observers were reluctant for the RBA to raise rates again.

As Deloitte Economics Partner Stephen Smith put it:

‘It’s the rate rise the Australian economy didn’t need,’ he said.

‘With increases to the cash rate only effective at reducing demand-led inflation, it is hard to see what the November rate hike achieves other than making it harder for Australians to pay their mortgage in the lead-up to Christmas.’

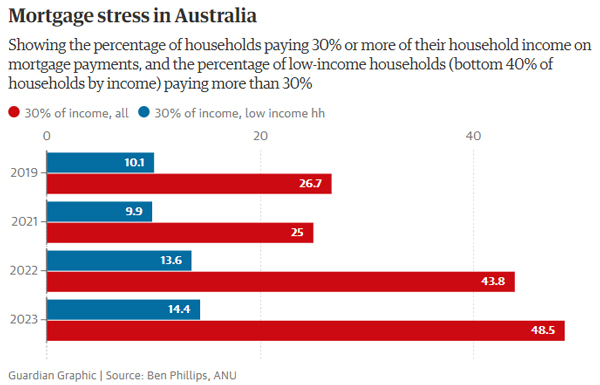

According to the latest ANU data, nearly half of Australians face mortgage stress and spend at least 30% of their disposable income to service their loans.

That was before the latest hike, which added another $105 a month to the average Sydney mortgage. The 13 rounds of hikes have added $60,000 a year in payments to the average Sydney mortgage holder.

| |

| Source: Guardian — ANU |

According to the IMF, Australia now has the highest level of debt pain in the developed world.

‘Mortgage repayments as a share of income are currently the least affordable in the history of our analysis in all cities except for Brisbane and Perth,’ writes CBA economist Harry Ottley.

‘Median income data in the ABS employee earnings survey indicates repayments Australia-wide are approaching the levels seen in the late 1980s when the standard variable rate peaked at 17%.’

With more households facing mortgage stress, retail spending has flatlined for 10 months. While this was ultimately the RBA’s plan to bring down inflation, it can go too far.

As AMP chief economist Shane Oliver put it:

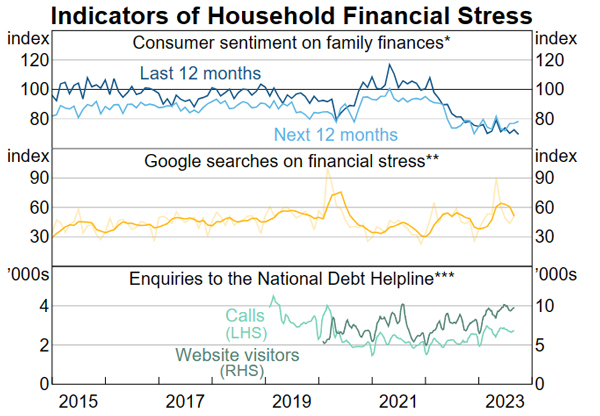

‘More recently they’ve been trying to balance cross-currents. On the one hand, we’ve still got high inflation, but on the other hand, there are increasing signs of household mortgage stress,’

With this stress building up, more people are using credit cards to cover bills on both sides of the Pacific. In the States, credit card debt just surpassed US$1 trillion, with the average consumer now spending $1,600 monthly on their credit card.

And in Australia, the number of calls to the national debt hotline has risen by 25%.

| |

| Source: ABS |

A fragile state

We stand at a slippery slope, where the interplay of high interest rates, towering debts, and the fragility of household finances create a challenge for the global economy.

On the horizon, we also face increasing costs for addressing climate change, and funding healthcare and pensions.

These are going to demand budget deficits at a time when we desperately reign in debt. On the other hand, any belt-tightening across government budgets could mean another lost decade of anaemic growth.

In this fragile environment, governments continue to spend themselves into a corner where a misstep could mean a sizeable market rout.

For now, debt is manageable, but the outlook is worrying, given longer-term spending needs.

The path down the mountain demands prudence, resilience, and reform for our Western partners.

Regards,

|

Charlie Ormond,

For Fat Tail Daily

Comments