Warren Buffett once said he considers himself a business analyst, not an equities analyst.

He seeks wonderful businesses with sustainable competitive advantages. Success lies in his ability to sniff out such companies.

But buying great businesses isn’t enough.

You have to buy great businesses at the right price. And the price is set by market expectations.

Investment returns stem from a misalignment between market expectations and business reality.

Wealth creation versus value creation

A good business may not be a good investment. There is a difference between creating value and creating wealth.

Credit Suisse’s valuation expert Bryant Matthews put it this way (emphasis added):

‘A firm creates economic value by investing in projects that beat its cost of capital. If the growth in investment or the return on investment does not meet the market’s expectations, the firm will underperform the market and fail to generate shareholder wealth. Good companies don’t always make good investments, particularly when expectations are high.’

On the stock market, gains are driven not by business performance but business performance relative to expectations.

Valuation guru Tim Koller has a nice sporting analogy for this idea (emphasis added):

‘Investing in the stock market is like betting on a sports team, but with a point spread (a point spread is the excepted difference in points at the end of the game). When spread exists, you cannot just pick the team you expect to win. You have to beat the spread (of you pick the favourite team, the favourite has to win by more points than the spread for the bet to pay off. Thus, picking a good team is not enough. The team has to beat expectations.’

A premiership team is expected to beat the wooden spooners. You won’t make much wagering on that outcome.

But the premiers winning by 100 points is less expected, and betting on that outcome can pay off handsomely…if it ends up happening.

Alternatively, if the premiers win but only win by a point, the result is disappointing. Although the premiers won, they didn’t win by as much as expected.

Expectations matter. A lot.

My colleague Callum Newman touched on this topic yesterday when he wrote about the recent rally of retail stocks:

‘Just in the last few weeks, I’ve seen positive updates from Myer Holdings [ASX:MYR], Accent Group [ASX:AX1], Cettire [ASX:CTT], and Super Retail Group [ASX:SUL].

‘They’re cashing in on the surprising strength in consumer spending.

‘The Australian Financial Review reports that the Black Friday shopping extravaganza is on track to set a record.

‘I did my bit and ordered a Nintendo Switch for the seven-year-old.

‘The point around this is that it’s not some airy-fairy observation.

‘There are tradeable moves that spring from this!

‘Cettire, for one, rallied 189% from early October to mid-November.

‘Stone the crows!

‘Why so dramatic?

‘A major part is that the market became way too bearish about the future economy when it collapsed back in June. That set terrible expectations about future results.

‘Now those results are coming out…and are much “less bad” than assumed. Shares rally when this happens.’

Shares rallied on better-than-expected performance. Expectations again played a key role.

High P/E stocks and great expectations

Through the expectations prism, we can look at the price-earnings multiple slightly differently.

High P/E stocks don’t necessarily imply overpriced stocks so much as stocks burdened with high expectations.

That’s a tough burden to bear. For some, the weight is too much.

High P/E stocks usually imply the market has strong expectations of enticing growth ahead. But stocks with high-growth expectations often fail to deliver.

Credit Suisse’s HOLT research unit published research in 2014 studying shareholder returns to stocks with high-growth expectations.

High expectations did not correlate well with high returns:

‘HOLT shows that cumulative shareholder returns to stocks with high growth expectations frequently lag shareholder returns to firms with much lower anticipated growth.’

These findings have intuitive appeal.

Take the extreme case of a business expected to take over and dominate its industry.

In that scenario, the business has a narrow path for success in terms of shareholder returns. Anything less than industry dominance is a disappointment to a market expecting just that.

And a business in the same industry overlooked by the market as a big player who suddenly captured 15% of the market will surprise investors to the upside, exceeding their expectations.

Great expectations — BNPL edition

HOLT’s findings also play out here on the ASX.

What industry did the market place very high expectations on in recent memory? The ‘Buy now, pay later’ sector springs to mind.

BNPL is the new way to pay. It will revolutionise the financial sector. BNPL firms will disrupt the big banks. Afterpay and Zip will be bigger than Visa and PayPal.

In the euphoric early days, sentiments like the ones above wound their way into the market’s expectations.

That led to steep share price gains. At one point, Afterpay was worth more than $45 billion, trading at 60-times sales.

Talk about high expectations.

But high expectations are fragile and brittle — it doesn’t take much to break the spell.

Growing competition, impatience with continued losses, and rising costs of capital all factored into the market’s disenchantment with BNPL.

Take Zip.

From March 2020 to its peak in February 2021, Zip gained 870%. Since then, the stock is down 94%.

Over the last five years, ZIP shares have gained just 1%. In the same span, the ASX 200 gained 20%.

Back to that Credit Suisse research:

‘Historically, stocks with high growth expectations generally underperform stocks with low growth expectations.’

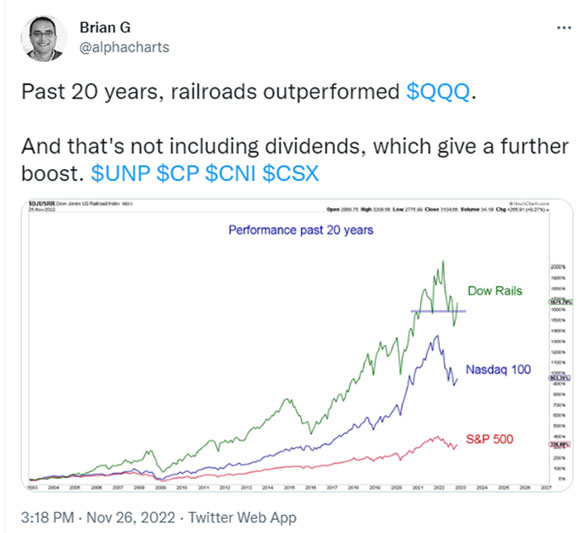

Look at railroad stocks.

Railroads were often seen as bad investments…capital-intensive, high fixed costs, and variable revenue.

You wouldn’t consider railroads as high-growth businesses. So expectations were low.

Yet over the past 20 years, railroads have outperformed the Nasdaq and the S&P 500:

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

Great expectations are a great burden.

As the HOLT research team quipped:

‘It is far easier for analysts to extrapolate growth in a spreadsheet than for managers to deliver it (a 15% annual growth over 5 years equates to a doubling of business).’

Until next week,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning