Seven interest rate cuts between 2024 and 2025?

That’s the big call from Westpac this week as the economy shows signs of sliding toward a recession.

GDP increased by 0.5% over the December quarter, falling well below expectations. And the household savings ratio has plummeted to just 4.5% — far from its high of 23.7% in 2020.

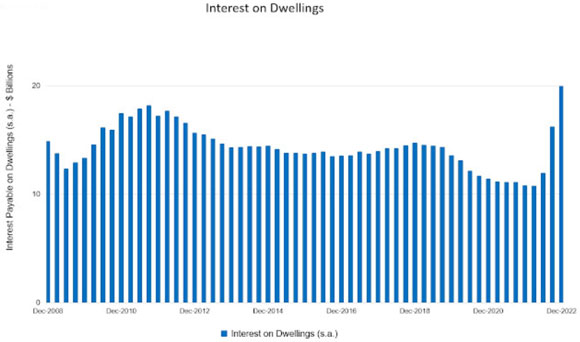

It’s clear where the money is flowing.

Real estate, of course.

Although not the ‘mum and dad’ investors that hold an investment property or two.

Rather, it’s the financiers — the biggest beneficiaries of rising rates — that have a licence to mortgage the earth and reap from the never-ending streams of interest.

Take a look…

|

|

| Source: ABS |

No wonder the majors are raking in record profits.

CBA recorded a record $5.1 billion profit for the second half of 2022.

And NAB’s $2.15 billion profit for the fourth quarter of 2022 was a quarter of a billion dollars above expectations.

By the way, if the RBA does overswing and is forced to perform a sharp U-turn into 2024/25 — it would make now a great time to buy property.

The problem is many are stuck in what’s being termed ‘mortgage prison.’ (An interesting quip considering mortgage is a French Law term meaning ‘death contract’.)

Borrowers want to access finance but are tapped out under current constraints.

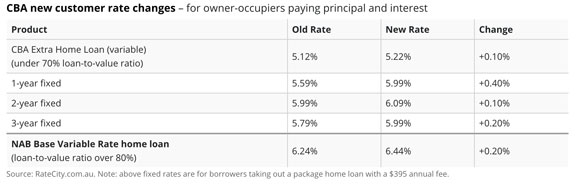

Rising rates is one issue, with news just in that the two record-profit-taking institutions — CBA and NAB — are hiking up the variable rates on some of their home loan products outside the official cash rate adjustment cycle.

|

|

| Source: Australian Property Investor |

But also, there’s news that APRA (at least for now) is holding firm on the 3% serviceability buffer that’s added to a lender’s interest rate for loan assessment purposes.

There was speculation that it would be reduced.

APRA Chairman John Lonsdale commented, prior to the release of its review on macroeconomic policy a few days ago, that the regulator would consider readjusting its rules to respond to lower credit growth or house prices.

But later said that the 3% buffer would remain in place ‘due to the potential for further interest rate rises, high inflation, and risks in the labour market.’

It could still happen, of course.

Nothing is set in stone.

There’s enormous pressure from many industry sectors to reassess the impact the 3% buffer is having on new and existing mortgage holders.

Including the Finance Brokers Association of Australia (FBAA):

‘“More borrowers are becoming ‘mortgage prisoners’, locked into a situation where they can’t access a better deal because they don’t meet the inflated assessment rate,” said FBAA managing director Peter White.

“Others may be forced into selling their homes because the excessive buffer rate holds them prisoner to their current lender as rates rise…”

‘“A 3% buffer was appropriate in the past because interest rates were at an all-time low and were always going to rise significantly, and this protected both the banks and the borrowers, but we can’t live in the past,” he said.’

And, of course, recent scrutiny on RBA governor Philip Lowe — as he was hauled in front of the Senate to explain why he was ‘determined to send Australia into recession’ (or words to that effect) — was a clear call to ease the foot off the accelerator.

Falling property prices are not a good look in a country where the financial system relies on increasing property prices, and policymakers overemphasise the so-called ‘wealth effect.’

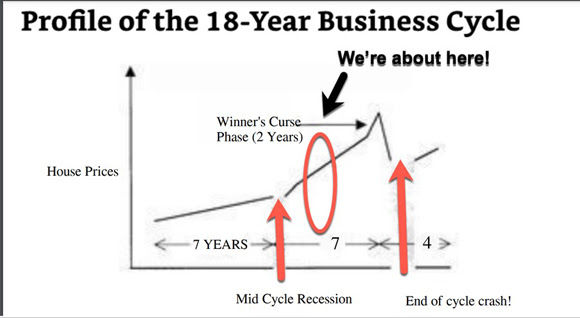

For our purposes, however, we need to look at this within the context of the 18-year real estate cycle.

Immigration, property shortages (in both the sale and rental markets) and buyer incentives — a swing from stamp duty to land tax in NSW, for example — can all assist in buffering the impact of rising rates on falls to median values.

However, we’re not going to get the real take-off in prices that we would expect into the peak of this cycle without some ‘give’ from the finance side.

Historically, the most inflationary period for real estate prices is in the last two years of the cycle. Fred Harrison termed this as the ‘winner’s curse’ phase.

In Fred’s words from his book, Boom Bust: House Prices, Banking, and the Depression of 2010:

‘The winners curse the third phase of the 14-year growth period last for about two years.

‘The trades in housing are now almost exclusively driven by the motive to speculate in the prospect of reaping huge windfall gains.

‘The price of land takes off in an almost vertical trend under the influence of what is known as the winner’s curse.

‘This is a period of frenetic trading in which prices can no longer guide people towards rational decisions based on what something is worth.

‘This is most evident in the real estate market investors become reckless to the point where the winning bids for property are made by people who make the greatest upward errors in their assessment of what a site is worth.

‘The psychology is primitive the property must be acquired at any cost.’

You can see it pictured on the stylised chart that I’ve sketched below.

|

|

| Source: Catherine Cashmore |

Within the context of our analysis, we usually see interest rates rise in the second half of the cycle in response to an improving economy — and rises in median house prices therefore follow.

Increases are frequent throughout the period — and small rises, in this context, are not a risk to the property market.

If you look at the peaks in the previous cycles (1973, 1989, 2008), rates increased along with prices because the economy was going well due to the tidal wave of credit created that was lent out for speculation.

However, sharp and frequent rises in lending rates — specifically to slow property speculation — typically occur around two years out from the peak, during the ‘winners curse’ phase of the cycle.

To quote Fred Harrison’s book again:

‘In 2004, The bank of England’s monetary policy committee (MPC) raised interest rates without a full understanding of the impact on the housing market.

‘Its economists did not know what the consequences would be on people’s consumption decisions or the direction in which house prices would move.

‘It was no comfort to be told by Mervyn King — the governor of the bank of England.

“I do not know where house prices are going — but I also know that no one else does either.”’

This pattern has been very predictable in previous cycles — which eventually triggers the downturn.

The productive sectors of the economy have been eroded with so much lending levied against property speculation that the ‘real economy’ is no longer able to service the debts.

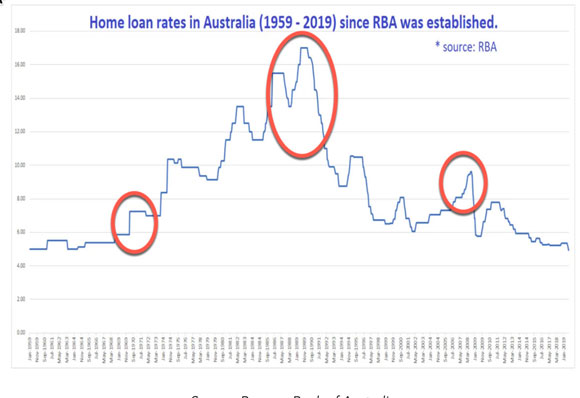

You can see this on the chart below, showing historical home loan rates in Australia.

I have circled the points at which lending rates increased rapidly in the three previous cycles.

Always sharpest during the ‘winner’s curse’ phase of the real estate cycle:

|

|

| Source: RBA |

Therefore, we wouldn’t usually expect rates to plummet between 2024/25 as forecast by Westpac.

However, let’s face it. Nothing has been typical about this current cycle.

It’s been volatile since the onset.

The 2008 crash was averted by Kevin Rudd’s massive incitive program that ushered in home buyer (or better-termed homeowner) grants of $30K-plus.

That produced a rise in the national median of 25% between 2009 and 2010, while property markets in Europe and the USA were tanking.

The sharp downturn in reaction to the Royal Commission into the Banking sector in 2018 gave us a particularly sharp downturn in real estate values outside of the mid-cycle recession — plummeting the national median by some 10%.

The dramatic U-turn in 2019 (when any prospect of a hit to negative gearing and capital gains tax incentives was eliminated with the Libs’ win at the Federal election) was the sharpest I’d ever witnessed.

And the monumental stimulus pumped into the economy in reaction to the pandemic, coupled with record-low lending rates, saw median prices rise at their fastest rate since the winner’s curse phase in the late 1980s.

A pullback was inevitable.

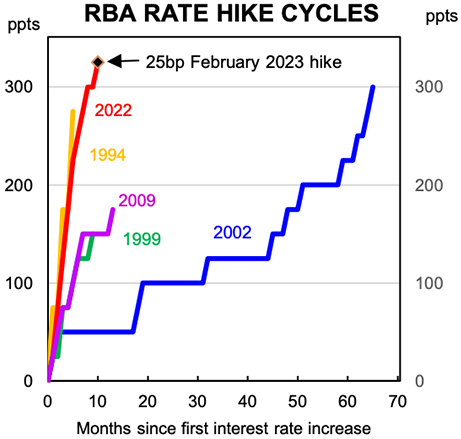

Still, no one expected the sharpest rate hiking cycle in living memory to hit the markets so early in the cycle.

|

|

| Source: Pete Wargent’s Daily Blog |

Therefore, we wouldn’t usually expect rates to plummet between 2024/25 as forecast by Westpac.

However, let’s face it. Nothing has been typical about this current cycle.

It’s been volatile since the onset.

The 2008 crash was averted by Kevin Rudd’s massive incitive program that ushered in home buyer (or better-termed homeowner) grants of $30K-plus.

That produced a rise in the national median of 25% between 2009 and 2010, while property markets in Europe and the USA were tanking.

The sharp downturn in reaction to the Royal Commission into the Banking sector in 2018 gave us a particularly sharp downturn in real estate values outside of the mid-cycle recession — plummeting the national median by some 10%.

The dramatic U-turn in 2019 (when any prospect of a hit to negative gearing and capital gains tax incentives was eliminated with the Libs’ win at the Federal election) was the sharpest I’d ever witnessed.

And the monumental stimulus pumped into the economy in reaction to the pandemic, coupled with record-low lending rates, saw median prices rise at their fastest rate since the winner’s curse phase in the late 1980s.

A pullback was inevitable.

Still, no one expected the sharpest rate hiking cycle in living memory to hit the markets so early in the cycle.

Best Wishes,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor

Comments