The world of bonds is an arcane one.

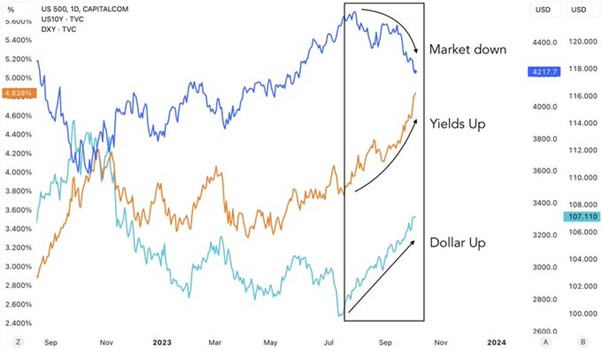

Since the beginning of August, we have seen bond yields rise as stock markets fall.

But a rise in bond yields isn’t great news for the economy.

Simply put, a rise in bond yields means that bond prices are falling. But how does that work?

Source: Zerohedge

What are bonds and bond yields?

Bonds can be issued by companies or governments who want to raise money. They can be thought of as an IOU between the lender and borrower.

Bonds typically pay the owner of the bond (the lender who bought it off the government) a fixed income and then pay back the full amount of the bond upon the end date of the bond agreement, known as maturity.

Governments, companies, and other organisations issue them to raise money to pay for large projects and investments, like bridges or new developments.

Bond yields are the amount of money an investor expects to receive each year over the term of the bond to maturity.

So when the price of a bond falls, its cost goes down but the fixed income gained from it is worth relatively more, so you would say its yield goes up.

The yield can also be seen as the ‘cost of borrowing’ to an issuer. So if a government, for example, issues new bonds when their prices are falling, they will get less money for their IOU while also having to offer higher interest rates to attract investors.

The bond market is the biggest market in the world, worth US$133 trillion.

The US bond market is the largest, accounting for about 40% of debt worldwide.

So when you hear bond yields are rising, like we have seen recently with 10-year treasury bond yields hitting 16-year highs, you can also interpret that as bond prices collapsing.

In the US, the bond market has been in a drawdown for 38 months, by far the longest bond bear market in history.

Tiny bit of history

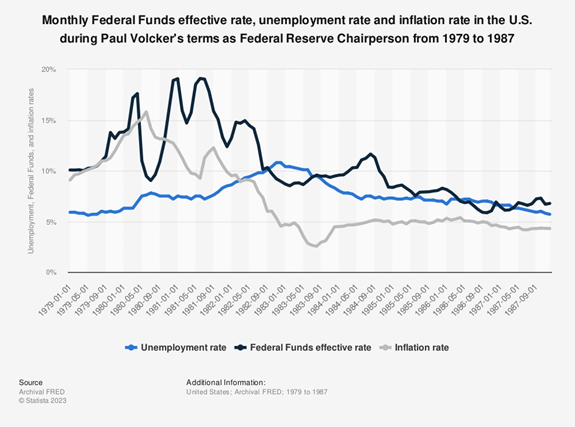

It’s important to look back because we’re moving into market conditions similar to the economic meltdown of 1981–2.

At the time, Fed Governor Paul Volcker took a dogged view on controlling inflation over all other concerns.

As he said in ’76, ‘in terms of economic stability in the future, [inflation] is what is likely to give us the most problems and create the biggest recession’.

He followed through on this, surprising the market with a similar call to today, with ‘higher [interest rates] for longer’ and more aggressive monetary control than investors expected.

As he put it, a ‘failure to carry through now in the fight on inflation will only make any subsequent effort more difficult’.

This led him to put through a series of aggressive monetary policy measures known as ‘Volcker Shock’.

Source: Statistica

While painful for the economy, it ultimately brought inflation from over 14% in 1980 to 3% in 1983, leading some to consider Volcker the greatest Fed Chair in history.

Back to the present

This year, bond yields have been rising sharply in 2023 (remember, this means bond prices are collapsing) as investors anticipate that central banks worldwide will hike interest rates to combat inflation and keep them high until they finish the job.

The yield on the 10-year US Treasury note, a benchmark for global bond yields, rose from around 3.8% at the beginning of the year to more than 4.8% on Wednesday.

It has since eased slightly to 4.73%, but the last time we saw bond yields at 4.7% was in 2007 — another auspicious year.

There are a few factors driving the rise in bond yields. First, the Federal Reserve interest rates to a peak of 5.25-–5.5% so far this year.

It’s remained hawkish that it could rise again in an effort to bring inflation down from the 40-year high we saw earlier in the year.

Second, investors are becoming more concerned about the risk of a recession. The global economy is holding up, but there are still chances we could fall into a recession.

Investors have a falling appetite for holding long-term bonds when there’s a perceived growing risk of long-term default for economies or national finances.

As a result, investors demand higher compensation for lending money for longer periods of time. This is known as the term premium.

Source: CrossBorder Capital

The term premium (in orange) is rising rapidly in recent weeks with the market concerned about the ‘higher for longer’ rhetoric sparked by the September Fed meeting.

The reasons for the ‘higher for longer’ regime are, in part, thanks to the resilience of the US economy. Job numbers are higher than many were expecting and this, combined with rising oil prices, has raised concerns of ‘embedded inflation’.

This pushed the Fed under Jerome Powell into a position similar to Paul Volcker in the 80s, so he’s gone on the aggressive.

The market is now believing his hawkish rhetoric and is reacting, sending bond yields to historic highs.

What do these rising bond yields mean?

Rising bond yields have made borrowing money more expensive for governments and businesses. This could lead to slower economic growth in the future.

To try to raise money, the government will have to sell bonds (and has been) with higher yields in order to make them attractive to cautious investors, meaning the ‘cost of borrowing’ for governments goes up.

Back in the 1980s, debt-to-GDP was 32%. It’s now more than 120% and climbing.

In 2022, it cost the US Government US$476 billion to pay the interest on its debts, that’s around 2% of the national GDP.

With higher interest rates and rising yields, this is predicted to reach 4% of GDP by 2030.

Another impact of the rise in bond yields has been a sell-off in stocks, as they are often seen as competing asset classes. When bond yields rise, stocks become less attractive to investors.

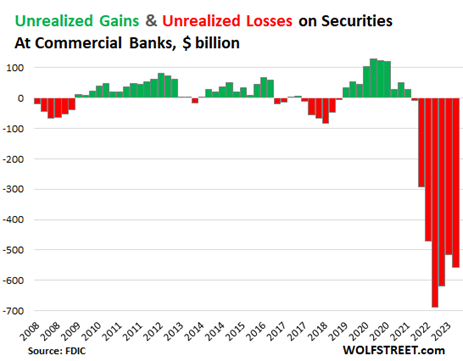

The rise in bond yields has made existing bonds less valuable. This is because investors can now buy new bonds with higher yields. This has led to significant losses for bond investors or holders.

Government regulation and financial prudence by many institutional investors mean they usually hold large quantities of bonds as a safe asset or hedge against losses in other equities.

A good example of this is banks, where many are forced to hold capital as security. This security is held as bonds with a very long maturity, the kind that is becoming worthless in the changing bond landscape.

Small US banks hold about US$900 billion of treasuries. As yields have been surging continually, unrealised losses on banks’ balance sheets have continued to accumulate. If this continues, we’ll likely see more stress in the financial system and probably even more bank failures.

Source: Wolfstreet.com

The US does have systems to try to relieve this pressure, such as the Bank Term Funding Program, which was set up after the sudden failure of smaller banks earlier this year, but the pressure is still on.

Similar problems have been seen in other markets, with varying intensity. Former British PM Liz Truss’s infamous mini-budget of 2022 similarly upended the bond market. The consequences of this were ultimately her famously being outlasted by a head of lettuce.

That pressure could mean companies are unwilling to borrow and invest for the future, and countries tighten budgets and pull in spending, leading to an eventual slowdown of the economy.

There is also a risk of a feedback loop, in which the higher interest rates push the value of the US dollar higher, which motivates foreign US debt holders to sell their US bonds as a means to generate money to pay off their climbing US debts from the appreciating dollar.

The flooding supply of bonds from these sales then further pushes bond prices down and then pushes rates up, which then cycles back to pushing the dollar up.

As head of global currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman & Co, Win Thin, said,

‘It’s firing on all cylinders,’ he said. ‘Strong data, higher yields, and hawkish Fed talk are all very positive for the greenback.’

This feedback scenario is just one way things could go, the Fed is likely to step in if things get crazy. But there is always a risk when one signal in the market steps out in front of the rest.

Thankfully, bonds and oil prices have eased from their highs but these bonds are still weighing heavily on many parts of the system.

Where it goes from here is worth keeping an eye on.

Regards,

Charles Ormond

For Fat Tail Daily