Date: July 2022

What do pencils and smartphones have in common?

These days, a smartphone is as essential to the human experience as running water and electricity.

And, although we think of smartphones as high-tech, both smartphones and pencils require graphite.

Graphite’s many uses — like our smartphones — are anything but modest.

We’ll get into why that’s the case later, where we’ll cover all the new and exciting applications of graphite that are driving global demand every day.

Navigate to a section quickly:

- What is graphite?

- Graphite types

- Main uses of graphite

- Lithium-ion batteries

- Metallurgy

- Fire-retardant

- What about graphene?

- How much does graphite cost?

- Who are the biggest graphite producers?

- ASX Graphite Stocks

What are the graphite stocks on the ASX? And are they worthy of investment?

Well, the answer is far from a straight yes or no.

Nowadays, with the increase of technology development in all industry sectors, many natural elements have experienced a surge in demand. Graphite being one that is particularly sought after, due to its variety of uses.

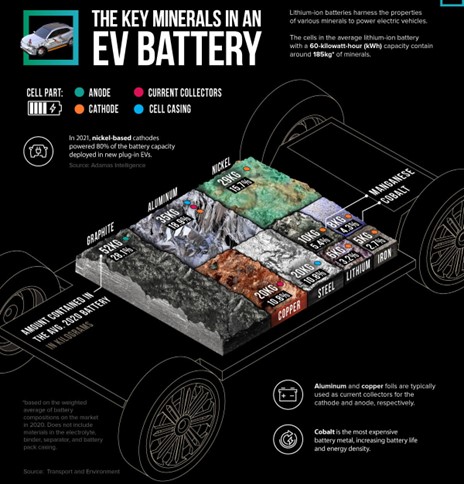

One of the main uses of graphite these days is as a key ingredient for lithium-ion batteries —which actually consist of a lot more graphite than lithium!

The EU and the US have both dubbed graphite the all-important definition of a ’critical mineral,’ which has resulted in many graphite-focused ASX stocks gaining popularity.

In this article, we’ll walk you through everything you need to know about graphite and graphite-focused ASX stocks — their benefits and shortcomings. Only then will you be able to decide whether or not they’re a good investment for your own portfolio.

What is graphite?

Before we get into graphite stocks on the ASX, we should cover the basics.

Graphite — also called plumbago or black lead — is a mineral consisting of carbon.

Graphite is chemically inert — meaning it is a material that is generally not reactive, and making it less prone to volatile chemical reactions.

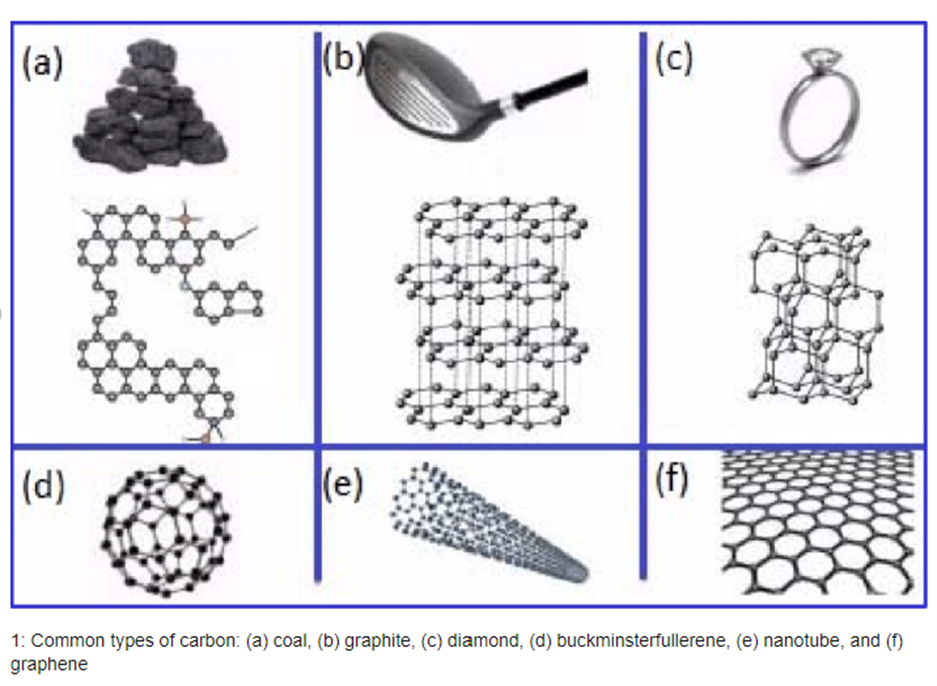

Interestingly, graphite, diamond, and coal are all common types of carbon; their differing atomic arrangements account for the difference in appearance:

Source: Ali Al-Matar

Graphite is a grey material with electrical conductivity qualities that help batteries store more energy and charge faster — perfect for electric vehicles (EVs).

The rising popularity of EVs has been sparking an ever-growing interest in graphite, especially as it plays an important role in reducing emissions and decarbonisation.

Graphite, coal, and diamond are the only three naturally occurring forms of carbon. They have the same chemical formula, but their atoms are arranged in different patterns and have different characteristics.

While microcrystalline graphite may easily be mistaken for coal, higher-grade graphite looks like flakes, chips, or smaller lumps.

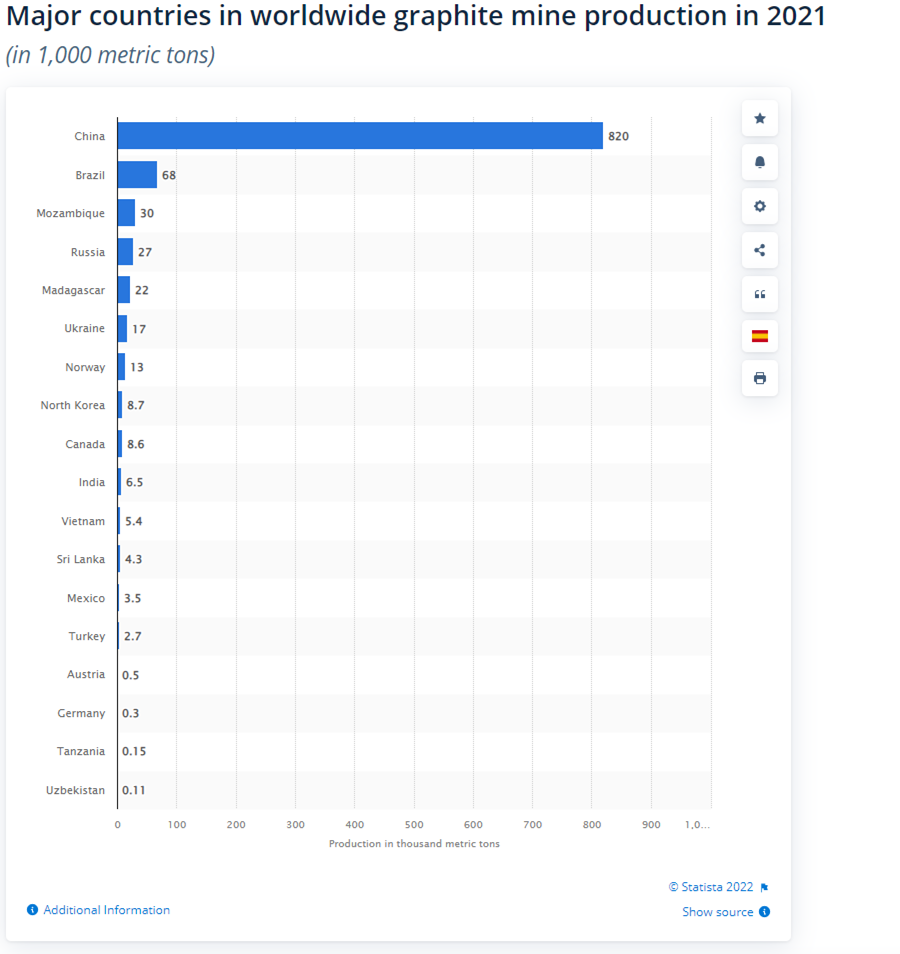

In practice, most of the higher-grade stuff comes from Sri Lanka. However, China still produces the largest amount of graphite by far.

Source: Statista.com

Graphite types

There are two main types of natural graphite: microcrystalline and crystalline graphite.

Microcrystalline graphite has a lower graphitic carbon percentage and has an appearance much like high-grade coal. It represents around 60% of the graphite market. The carbon content of this graphite is usually between 70% and 85%, and it’s mostly used for lubrication.

Crystalline graphite on the other hand, can come in the form of lumps and flakes of different sizes — which have a higher carbon content, but are found in smaller quantities and at deeper depths.

The other natural graphite is flake, lump, or chip material. The flake graphite comes in a variety of sizes and coarseness, with a carbon atoms content ranging from 80–98%. This is rarer than powder graphite, and of superior quality.

Other than natural graphite, there are a few types of processed graphite that also have significant importance in the industry. One of the most widely used processed graphite types is:

Expanded graphite

This type of synthetic graphite is produced by treating graphite flakes with acid and heat, which makes them split apart and increase in volume by up to 300 times. It’s then pressed into thin sheets that can be used for heat and fire protection.

Thanks to it’s heat resistance, expanded graphite is used in building materials as a requirement of higher safety standards. For the same reason, it’s also used in different consumer electronics, fuel cells, and other items.

Graphite’s rapidly growing demand could also be attibuted to laws imposed on countries that require flame-retardant materials for the building of flats and homes. Flame retardants are required in building codes in China, the EU, Japan, and Korea, where brominated and asbestos-based flame retardants are banned.

China requires 40 million tonnes of flame-retardant construction materials a year, 5% of which contain expandable graphite. This means China’s construction sector alone requires two-million tonnes of expandable graphite every year.

Spherical graphite

Spherical graphite is another important type of synthetic graphite. It is produced from flake graphite by increasing its carbon atom content to excess of 99.95%.

It’s also especially sought after in the lithium-ion battery market due to its impressive electric conductivity, which is very important for successful anode production.

Spherical graphite is costlier than natural graphite, but is widely used in certain industries that require higher carbon atom purity.

Now let’s take a closer look at how graphite is being used…

Main uses of graphite

We’ve used graphite throughout history — the first known uses were dated around 750 BC. Back then, potters used it to create paint for decorating ceramics.

About 15 centuries later, English shepherds would use low-grade graphite to mark their sheep.

However, the most famous application of graphite would appear at the end of the 18th century, when Nicolas-Jacques Conté, a French inventor, combined graphite with clay to create the first modern pencil.

That’s where the name comes from — the Greek graphein, which means ‘to write’.

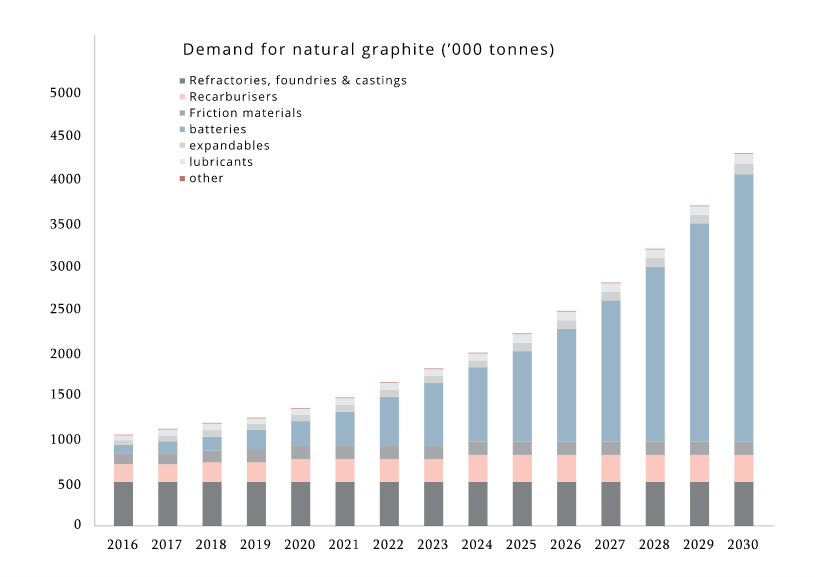

These days, graphite has many more uses, and as we can see in the graph below, demand is steadily increasing as a result:

Source:tirupatigraphite.co.uk

Lithium-ion batteries

The widespread adoption of certain technologies based on lithium-ion batteries is only likely to add to graphite’s increasing demand.

Take EVs, for example.

With current production methods and technologies, the average EV battery contains up to 70kg of graphite.

Source: Visual Capitalist

Since an EV battery’s anode is mostly graphite, graphite is actually the largest mineral component of the battery.

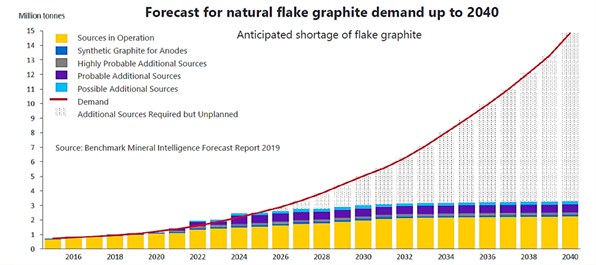

Some analysts predict growth in demand may soon outpace supply, especially when it comes to smaller flake sizes.

By 2040, demand for lithium-ion anodes is expected to grow by 27% on a yearly basis.

Source: Tankaengineers.in

The mineral’s non-metallic properties include; its high thermal stability and its capacity to withstand chemical reactions. This has led to graphite finding applications in coatings, pencils, consumer electronics, crucibles, and refractories — where these qualities are most desired.

Graphite’s key metallic qualities include electrical and thermal conductivity, and it has both metallic and non-metallic properties.

It’s these properties that are making it so attractive in lithium-ion battery production.

Metallurgy

Another driver of demand for graphite has been the material’s use in metallurgy — more specifically, steelmaking.

Graphite is used to produce heat-resistant bricks that are used in the construction of blast furnaces.

The heat-resistant properties of graphite protect these furnaces from damage during the incredible heat produced in the steelmaking process.

Graphite electrodes are also used in LFP (ladle furnaces) and EAF (electric arc furnaces) for smelting, silicon metal production, ferroalloy production, and steel production.

Another use of graphite in the metallurgy sector is lining moulds used to cast objects made from different metals.

That’s because graphite is non-adherent to molten metal.

Lower-grade microcrystalline graphite is used for this purpose because it has a high melting temperature, and is more cost-effective than higher-grade graphite.

Fire-retardant

As we have mentioned, graphite has a unique ability to prevent fire by withstanding extreme heat.

When graphite is treated with a combination of acid and heat, its flakes can split and increase in volume — creating ‘expandable graphite’. This is what is pressed into graphite sheets.

The variety of applications of these fire-retardant graphite sheets grows with increasing demand for fire safety in both residential and commercial construction.

Incidents like the horrific Grenfell Tower fire in London, and the explosion that struck the Tianjin port in China, are driving new legislation across the globe.

Countries like Australia, prone to bushfires as we are, are limiting the use of non-flame-retardant construction materials, especially the aluminum cladding found on some buildings.

As we mentioned earlier, similar regulations are appearing across Korea, Japan, China, and the EU.

There are plenty of companies looking to get in on the action when it comes to expandable graphite production.

Take BlackEarth Minerals [ASX:BEM], for example. The company owns and operates the Maniry Graphite Project situated in southern Madagascar.

They’ve recently signed an agreement with the Metachem Manufacturing Company, with plans to build an expandable graphite production plant in India.

The two partners have already found a buyer willing to sign an offtake agreement — Austrian firm Grafitbergbau Kaisersberg has agreed to 2500tpa .

What about graphene?

Notably, graphite can also be used to create graphene — the thinnest material known to be in existence. Graphene is also famous for its immense conductivity and strength.

In 2004, two University of Manchester professors discovered graphene after using sticky tape to divide graphite fragments. In the process, they managed to create atom-thin graphene flakes.

By the end of the decade, they would receive the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery.

Today, the material is still on the cusp of mainstream use — but it’s already found applications in industrial robotics, green tech, aircraft, sensors, electronics, and even sporting equipment.

Graphene is an allotrope of carbon that can be obtained from graphite.

The main difference between them is; while graphene is a one-atom thin layer of carbon arranged in a honeycomb pattern, graphite consists of a three-dimensional arrangement of carbon atoms.

Graphene is considered the strongest material discovered to date.

Graphene is 40 times stronger than diamond — making it a more durable material.

A study conducted by The University of Massachusetts discovered that graphene has 8–10 times the stopping power of steel, and is twice as effective at blocking bullets than kevlar.

Because graphene is so light, researchers are currently experimenting with weaving carbon nanotubes (basically a tube of graphene) into fabrics for high-performance military and sports clothing.

Many more uses for graphene are being investigated — including in electronics, sensors, coatings, and water purification membranes, just to mention a few.

However, obtaining pure graphene with the adhesive tape method can be rather inefficient. For this reason, many companies are researching ways to mass-produce graphene with lower costs.

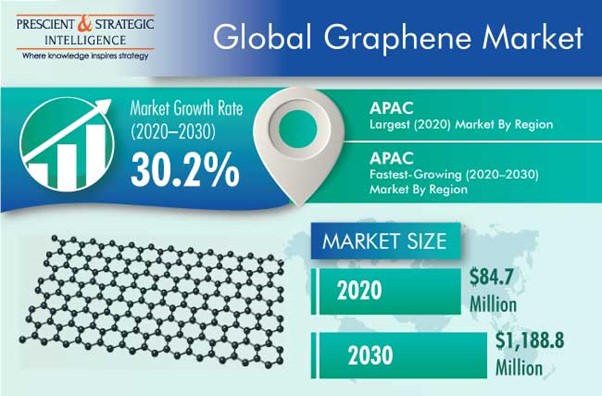

The global graphene market is projected to reach around US$1.2 billion by 2030, at a compound annual growth rate of around 30%.

Source: Psmarketresearch.com

How much does graphite cost?

Unlike markets for commodities like oil, the graphite market is relatively opaque.

Still, like any other commodity, the price of graphite depends on negotiations between buyers and sellers.

Nowadays, China is the biggest producer and seller of graphite, providing between 70–80% of the global supply of graphite.

Because of that, China has power to influence the price of graphite.

Since 2015, China’s government has taken a tougher stance on pollution and implemented major measures to solve the country’s environmental issues.

Production of commodities like graphite has significantly reduced on the closure of many mines and facilities as a result.

Due to China’s production restrictions, global graphite supplies have dropped in the last few years.

And while the demand for graphite rapidly increases, the price continues to grow.

Who are the biggest graphite producers?

According to the United States Geological Service (USGS), the top 5 countries that produced the biggest quantities of graphite in 2021 were:

- China

China produced around 820,000 tonnes of graphite in 2021, which is approximately 79% of the world’s graphite production.

- Brazil

Brazil has the third biggest graphite reserves and mined about 68,000 tonnes of graphite in 2021.

- Mozambique

Mozambique is well known for its large flake graphite reserves, and it produced 30,000 tonnes of graphite in 2021. This number is expected to increase when certain big projects that are currently under development start production.

- Russia

Russia produced 27,000 tonnes of graphite last year.

- Madagascar

Madagascar is the fifth-largest graphite producer in 2021, with a total graphite production of 22,000 tonnes. This number is expected to increase in the next few years due to graphite projects currently in development.

One honourable mention in this classification is Sri Lanka. Although it had a small graphite production of just 4,300 tonnes, ranked at number 10, it produces natural graphite with the highest carbon atom content.

ASX Graphite Stocks

If you are already interested in the graphite market and would like to invest in this quickly growing industry, here’s a list of ASX graphite stocks for you to consider.

Walkabout Resources [ASX:WKT]

Walkabout Resources procured a mining licence in Tanzania back in 2018, where it is developing its Lindi Jumbo project.

According to the company, this deposit has the highest-grade graphite mineralisation in Tanzania.

Novonix [ASX:NVX]

Novonix is the major (and current only) synthetic graphite supplier in the US with a Tier 1 battery cell manufacturer qualification — meaning that their synthetic graphite can be used for EVA production.

This battery tech stock produces synthetic graphite by treating amorphous carbon materials at extremely high temperatures.

The primary feedstock for synthetic graphite is coal tar pitch and calcined petroleum coke.

Novonix’s Chattanooga, Tennessee plant opened in late 2002. NVX hopes to produce 40,000 tpa by 2025.

The Chattanooga facility was previously owned by General Electric and was used to produce nuclear turbines up until 2016.

Subsequently, Novonix invested around $160 million in the retrofitting and acquisition of the plant to produce synthetic graphite.

To accommodate expanding industry demand, Novonix plans to boost manufacturing capacity to 10,000 metric tonnes of synthetic graphite per annum by 2023.

By 2025 and 2030, NVX plans to achieve additional targets of 40,000 tonnes and 150,000 tonnes, respectively.

Greenwing Resources [ASX:GW1]

Greenwing Resources (previously known as Bass Metals, [ASX: BSM] is a graphite mining company that owns a 100% stake in the flagship Graphmada project in Madagascar — which has large reserves of large flake graphite. It has full landholder rights over the area for 20 years, and a 40-year mining leasing licence in existence.

The Graphmada project is very promising, and the company is expected to start graphite production soon. Greenwing Resources has also announced that it has established sales agreements with clients from Europe, the US, India, Japan, and China for the graphite that will be mined from this project.

Apart from mining graphite, the company also has two lithium projects; one in San Jorge, Argentina, and one in Madagascar.

Battery Minerals [ASX:BAT]

Battery Minerals is an Australian company that is developing the Stavely-Stawell copper and gold project in Victoria, and the Russells Copper Project in Western Australia’s Kimberley region. It also has two major graphite projects in Mozambique, the Montepuez Graphite Project, and the Balama Central Graphite Project.

The two graphite projects in Mozambique are in an area with some of the highest-grade coarse flake graphite resources in the world. Because of that, these projects can be very profitable, and it might be a good idea to invest in this company.

According to the company’s research, the Montepuez graphite project has a mine life of 30 years, and it could produce 100,000 tonnes of graphite per year.

Triton Minerals [ASX:TON]

Triton operates the Ancuabe Graphite Project in Mozambique and is looking to expand its local capacities.

TON also recently signed an offtake agreement with Yichang Xincheng Graphite — a Chinese manufacturer of graphite products.

This agreement will see Triton shipping 10,000tpa of graphite from its Ancuabe-based commercial pilot plant.

Once the Ancuabe project is fully constructed and reaches its planned capacity of 60,000tpa, the deal may be altered to accommodate larger volumes.

Triton’s construction plans have been delayed by COVID-19.

First Graphene [ASX:FGR]

First Graphene is one of the biggest graphene producers in the world. First Graphene has a commercial graphene production facility in Australia that can produce up to 100,000 tonnes of graphene per year.

First Graphene’s top-tier PureGRAPH® collection of products is tailored for a wide range of industrial applications while exploiting the capabilities of graphene. It can be used in the production of coatings, inks, composites, elastomers, concrete, fire retardants, textiles, and many other uses.

Graphene is usually a very costly product, and companies that produce it on a large scale can enjoy rewarding profits. The graphene market is expected to reach $1.5 billion by 2025.

Syrah Resources [ASX:SYR]

Syrah Resources is an Australian company that currently has a 100% stake in the Balama graphite project in Mozambique, and owns a spherical graphite processing site in Vidalia, Louisiana, US.

The Balama project has an expected mine life of 50 years and produces graphite ores with a high content of carbon atoms, between 94–98%. It is also a very lucrative graphite project, according to company reports it produced 46,000 tonnes of graphite in the first quarter of 2022. About 35,000 tonnes were already sold and shipped.

Its spherical graphite processing facility has already produced samples for potential clients and is expected to produce 10,000 tonnes of spherical graphite for lithium-ion batteries anodes when it starts full capacity production.

Black Rock Mining [ASX:BKT]

Black Rock is an Australian mining exploration company with a 100% stake in the Mahenge Graphite Project in Tanzania. According to the JORC, it is among the world’s largest flake graphite reserves.

According to Black Rock’s statements, the project could produce around 340,000 tonnes of graphite with a 98.5% carbon atom concentration per year, for approximately 26 years. The company has also stated that the project has an operating cost of $397 per tonne, and it sells its graphite for around $1300 per tonne.

Talga Group [ASX:TLG]

Talga Group is an Australian incorporated company that is focused on exploring graphite resources and manufacturing high-quality anodes for lithium-ion batteries in Sweden. It owns three advanced projects in northern Sweden, which are Vittangi, Julkunen, and Raitajärvi.

Its high-end products are the Talnode™-C anodes, which are made from high-grade natural graphite produced in Sweden. It is advertised as ’the world’s greenest battery anodes’.

The future of ASX graphite stocks

The improvements graphite brings to the steel manufacturing sector, combined with its necessity to the lithium-ion battery industry, suggest a positive demand outlook for graphite.

The world where most of us drive EVs is a world hungry for battery tech materials like graphite.

But we’re not there yet, with EVs making up 8.3% of total light passenger vehicle sales in 2021.

So we are a while away from mass EV adoption…Meaning that plenty more EVs will have to be built — and plenty of battery tech metals like graphite mined.

All in all, demand for graphite is likely to grow in the medium-term due to the transition to Evs — as well as new-found applications for graphene.

All the best,

Kyrill Prakapenka