Have you ever wanted to start investing on the ASX but weren’t sure how to get started? Well, this guide is for you. Here we will answer all your questions about getting started with investing on the ASX. You’ll learn the essentials of researching, evaluating, buying, and selling shares. So if you’re interested in starting your investing journey but don’t know where to start, read on!

Let’s start with some basics

ASX stands for the Australian Securities Exchange. The ASX was created by the merger of the Australian Stock Exchange and the Sydney Futures Exchange in July 2006. Now, the ASX is one of the world’s top 10 listed exchanges by market capitalisation.

The ASX offers listings, trading, clearing, settlement, technical and information services, technology, and data services. As of August 2021, the ASX had a total of 2,019 companies listed on its exchange.

ASX operates markets for a wide range of asset classes. Some of these asset classes include equities, fixed income, commodities, and energy.

ASX’s business has four divisions: Listings, Markets, Technology and Data, and Securities and Payments.

ASX history

From the 1850s, numerous stock exchanges were formed in cities like Melbourne, Bendigo, and Ballarat.

In 1871, the Sydney Stock Exchange was formed. In 1882, it was Hobart’s turn, with the year marking the launch of the Hobart Stock Exchange.

Two years later, in 1884, the Brisbane Stock Exchange was established. A year later, the Broken Hill Proprietary Company (more commonly known as BHP) listed on the Melbourne Stock Exchange.

The years 1887 and 1889 saw the launch of the Stock Exchange of Adelaide and the Stock Exchange of Perth, respectively.

In 1937, the Australian Associated Stock Exchanges (AASE) — a forerunner to the ASX — was established. While Australia’s state stock exchanges had met on an informal basis since 1903, 1937 marked the formalisation of the association.

Finally, in 1987, the Australian Stock Exchange Limited (ASX) was formed on 1 April under legislation of the Australian Parliament. This involved the amalgamation of the six independent stock exchanges then operating in the states’ capital cities.

In 2002, the ASX listed the country’s very first ETFs, including funds tracking the S&P/ASX 200 and S&P/ASX 200 A-REIT indices.

Since then, listed funds like ETFs, REITS, Listed Investment Trusts and Listed Investment Companies have become a popular option with retail investors.

In 2006, the ASX and Sydney Futures Exchange merged, expanding ASX’s products to index options, interest rate securities, energy, and agricultural commodities.

The merger saw the ASX change its name from the Australian Stock Exchange to the Australian Securities Exchange, reflecting the diversity of financial and investment products now available to investors.

What’s the ASX market makeup?

The ASX is the eighth-largest share market in the world and the second-largest in the Asia-Pacific region.

The stocks listed on the ASX are divided into 13 sectors. They include resources, banking and insurance, telecommunications, information technology, media, and transport companies.

Investors can track the performance of individual sectors or the broader market by following ASX indices like the S&P/ASX 200 Index.

Understand your investment goals

Before investing, it is wise to assess your financial situation and outline your investment goals.

There are a few important considerations to make before you begin investing on the ASX. It is helpful to ask yourself some questions to get an idea of who you are as an investor.

These questions should include:

- Why are you investing?

- What is your risk tolerance?

- What is your investment priority?

- How much time do you want to spend on your investments?

It is also important to remember that all investments entail risks, and you need to understand these risks before trading.

Investing on the ASX

Australia is a nation of investors. Over a third of Australians own investments that are listed on the ASX. 46% of Australians hold investments outside of their home and super.

Investing on the ASX is a popular way for countless Aussies to preserve and build wealth for the future.

Among those who invest, more than half invest in direct shares on the ASX — cementing shares as Australia’s most accessible and widely used investment option.

Of 9 million Australian investors, 6.6 million (or 74%) hold shares or other on-exchange investments.

So why do we invest?

Since we’re not uniform, we all have different reasons for investing. Some of us focus on near-term gains, while some look far into the future, even their retirement.

When asked about their financial milestones over the next three years, respondents to ASX’s 2020 Australian Investor Study listed a variety of goals.

Goals varied from going on a holiday (50%), to becoming debt-free (34%), or saving for big-ticket items (25%).

Among investors, the most common goal of their investment selection is to build a sustainable income stream.

Why invest in shares on the ASX?

We can consider three factors as informing people’s decision to invest in shares. The first is capital growth.

Capital growth refers to the appreciation in share price. Investing in shares offers the possibility that their price may rise more than the initial purchase price.

Another factor is dividend income. Dividends are cash distributions from a business to its shareholders.

Companies may also offer dividend reinvestment plans where instead of receiving a cash payment, a shareholder can use the dividend amount they received to buy new shares in the company.

The third factor is tax. One benefit of share investing is that it can offer concessional capital gains tax. In most circumstances, the capital gains tax payable may be discounted by 50% for shares sold 12 months or more after purchase.

Additionally, dividends from shares are sometimes paid with franking credits attached, where franking credits pass on the value of any tax that the company already paid on its profits.

Note that tax policies can change. You should always consult your accountant or other professional taxation adviser.

How do I start buying shares?

It may seem obvious, but to buy shares you need someone on the other side of the trade willing to sell you shares.

It is the share market that provides the means for two parties to organise how many shares they wish to trade and at what price they wish to settle.

It’s also important to know that buying and selling shares requires the services of a stockbroker.

Source: ASX

Broadly, we can split stockbrokers into those offering you advice, and those simply executing your buy (and sell) orders.

Full-service brokers can help you decide what to buy and sell, providing you investment advice and information.

No-advice brokers, conversely, simply execute your orders.

There are also many online trading platforms where brokers offer services over the internet.

Online brokers can offer lower fees and the ability to access live share prices, research, and market commentary.

Some online trading platforms include CMC Markets, eToro, SelfWealth, Interactive Brokers, and Bell Direct.

Mobile technology has led to a proliferation of online trading platforms, so choosing one will require you to determine your goals, preferences, and trading style.

For instance, how often will you trade? How do you wish to place your orders — online, over the phone, or via a mobile app? Will you want exposure to international shares or only ASX shares?

The ASX website has more information on brokers, including a repository for finding brokers that suit your needs.

When you buy and sell shares on the ASX, you pay a brokerage fee for each trade. This is the stockbroker’s fee for executing your trade.

What does the market look like when I buy or sell shares?

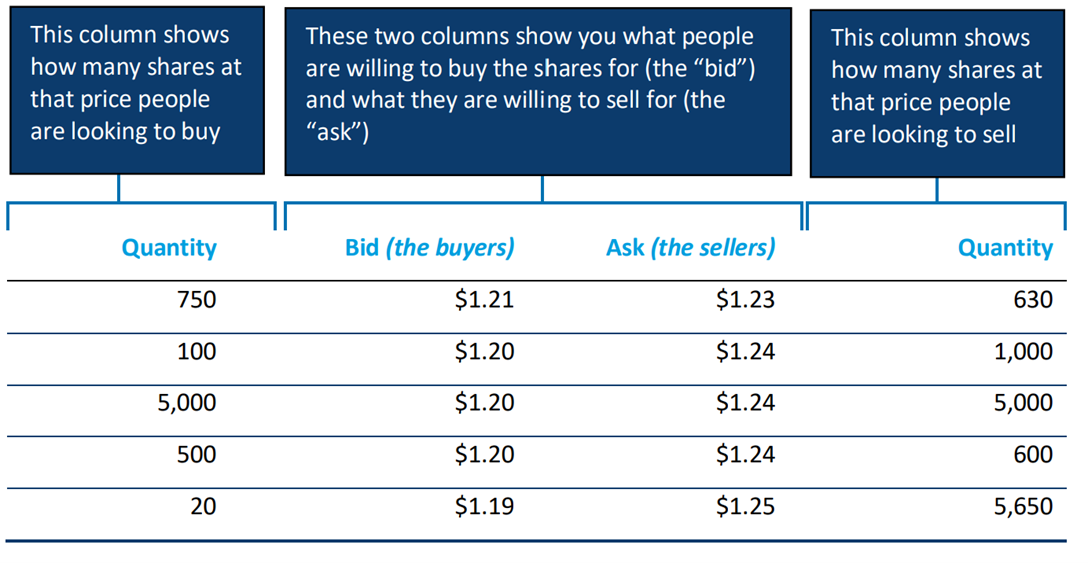

One of the hardest things to wrap your head around when first buying shares is understanding what the market actually looks like. The table below is the ASX’s own example of what you would typically see on a broker’s website when wishing to place a buy order.

The above table shows the ‘market depth’ for a particular stock — the number of buy orders and sell orders investors lodged in the market.

So when you’re contemplating making a buy order, you should consider share price, volume, and order type.

What price are you prepared to pay? How many shares are available to buy at that price? And what type of order are you lodging?

Buying shares and liquidity

The volume of buying and selling of shares in a stock is known as liquidity. Liquidity is an important consideration because the more liquid a stock, the easier it is to buy and sell that stock quickly at a desired price.

Less liquid stocks, with lower activity, may have a wider spread between the buy price and the sell price (what’s known as the bid/ask spread).

If you want to buy a larger quantity of shares in an illiquid stock, you may have to pay more than the current sell price to get your full order filled.

Simulating buying and selling shares

One thing you may consider before making your first ASX trade is simulating trades first.

If you’re contemplating investing for the first time and feel daunted by the risks and your inexperience, it’s often suggested to build a virtual portfolio and track its performance before investing real cash.

There are many stock market simulators and share market games you can participate in to practise your skills. For instance, the ASX runs the ASX Sharemarket Game, where participants invest $50,000 in virtual dollars.

Players can buy and sell shares in over 200 nominated companies, using live prices to simulate real market conditions.

Of course, share trading simulators can never replicate the emotions accompanying real losses and gains. Equanimity is harder when it’s one’s own savings evaporating instead of virtual currency.

Is buying shares on the ASX a gamble?

To answer this laced question, it’s worthwhile contemplating what it means to invest. Precisely who is an investor, and what distinguishes them from a punter?

Warren Buffett’s mentor, Benjamin Graham, famously distinguished between an investor and a speculator. For Graham:

‘An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis promises safety of principal and adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.’

Historically, the distinction between speculation and investing was often thin, evading clear consensus.

For instance, after the great market decline in 1929–32, all common stocks were widely regarded as speculative by nature.

But speculation is generally considered riskier than investment.

Investment requires a margin of safety, sound analysis, and a tight logic to the investment case. On the other hand, speculation is uninformed, spontaneous, and impulsive.

As historian Edward Chancellor wrote in his lauded history of speculation Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation:

‘The capitalist is confronted with a broad spectrum of risk with prudent investment at one end and reckless gambling at the other. Speculation lies somewhere between the two.’

How do stock market prices move?

Why is the stock market up or down?

News bulletins always begin their finance coverage by noting whether the major stock markets closed up or down on any given day.

For years now, the daily gyrations of global stock markets have received as much coverage as the weather.

But what does it mean for a stock market to end the trading day up or down?

Since the stock market refers to the aggregate prices of stocks sold on an exchange, when a stock market closes down it means that — on the whole — the prices of stocks traded that day fell relative to their price the day prior.

And vice versa when the stock market finishes up for the day.

Benchmarks like the ASX 200 are also frequently correlated with moves of larger stock exchanges like the Nasdaq.

For instance, the ASX 200 lost 160 points on 21 February 2021 after a tech sell-off on Wall Street.

Additionally, a potential reason why news publications so readily report on stock market fluctuations without much further context is because markets are complex, interrelated systems with hundreds of thousands of investors making uncoordinated decisions.

It is easier and less controversial to note the obvious fact that the ASX finished the session up than it is to pinpoint exactly why.

On a very basic level, markets tend to move toward equilibrium, where the supply of sellers equals the demand of buyers.

So when there are more buyers in a market than sellers, the buyers bid up stock prices to tip sellers into relinquishing their shares.

But this isn’t a complete answer. Because the question now shifts to why there are sometimes more buyers than sellers (and vice versa).

The answer to that question will inevitably be multilayered. The equilibrium of aggregate buyers and sellers might shift depending on macro events like a pandemic, changes in monetary or fiscal policy, rising inflation, supply shocks, and so forth.

Investment strategies

It may sound obvious, but it’s frequently overlooked: if you are going to invest, you need a strategy.

That strategy should reflect your financial circumstances, life goals, and risk tolerance.

Now, what is an investment strategy? It is a set of rules or guidelines you follow consistently.

Investors, unlike speculators, value a long-term perspective, matched by discipline, patience, and consistency.

Can you make money buying shares?

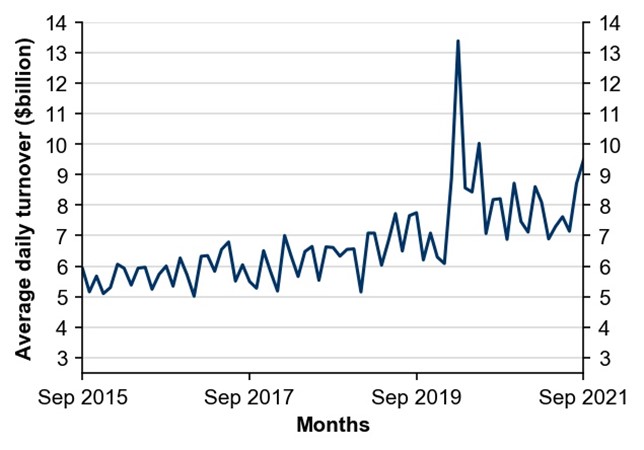

Reporting ASX equity data for the September 2021 quarter, ASIC noted that daily average turnover in the Australian equity market was $8.4 billion.

We would not see such volume and activity if capital growth was impossible.

Source: ASIC

Billions of dollars are exchanged daily as investors chase gains. And this prospect of gains must be real enough for participants, or the financial industry shrinks.

A commonplace truism of investing is that — generally and over the long term — the stock market tends to go up.

Risks elevate the more truncated your investment horizon. As another investing truism goes, it’s not about timing the market, but time in the market.

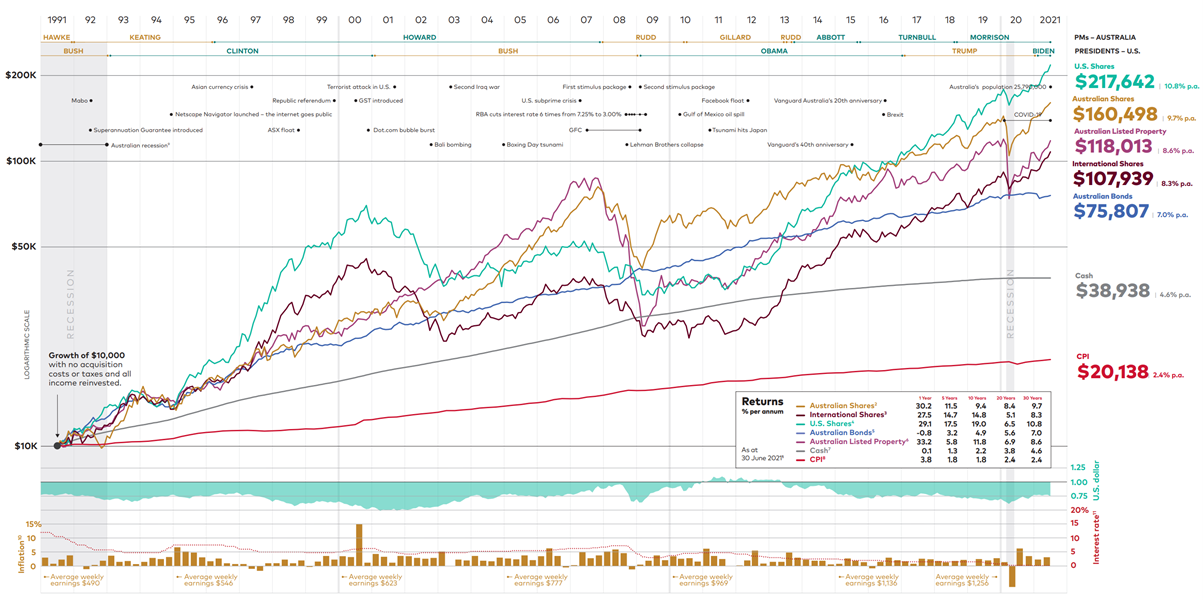

This is best highlighted by the chart below by Vanguard.

Source: Vanguard

The chart shows what a hypothetical $10,000 invested in 1991 would be 30 years later in 2021 if invested in different asset classes like Australian shares, US shares, and Australian bonds.

As we can see, $10,000 invested in Australian shares in July 1991 grew to $160,498 by June 2021, at an average of 9.7% per annum.

It’s important to remember that asset returns can vary, and this year’s strongest performer may end up being next year’s weakest performer.

While markets go up and down daily, the long-term perspective shows that consistent growth across different asset types over time is possible.

But it’s worth being realistic about risks — returns are never guaranteed in investing. Risk, however small, abounds.

Can you lose money buying shares?

Yes, you can. Investing is not risk-free and capital loss is always a possibility you must consider.

Earlier, we mentioned the prospect of capital gain driving stock market participants.

But beware the times when prospects of gain turn to anguish of loss.

For instance, the bursting of the Japanese asset price bubble in the early 1990s led to a post-bubble revulsion against stocks.

As Edward Chancellor wrote in Devil Take the Hindmost: A History of Financial Speculation, the aversion to stocks ‘was so complete that over 60 percent of Japanese personal assets were committed to cash bearing interest of less than 0.5 percent per annum.’

The ASX is a volatile market, and you must be aware of the risks.

How does buying shares help a company?

Put differently, why would a company want to issue shares to the public? Going public or initiating a capital raising lets a business raise money without tapping the debt market. The business can then allocate the raised capital to expanding its operations or paying for new equipment.

The funds raised by a company issuing shares is called equity capital. Unlike debt, which is borrowed money, equity capital does not need to be repaid.

What does buying shares on margin mean?

Buying shares on margin is a way of borrowing money from your broker to buy more ASX stocks than you could afford had you only used the capital at your disposal. To trade on margin requires a margin account, which is different from a regular cash account. It’s not generally recommended for beginners because it can be risky and expensive.

Why would more seasoned investors consider buying shares on margin? Buying on margin can offer an investor leverage to amplify gains. However, this practice can also amplify losses.

Understanding order types: what is a ‘limit order’?

Order types refer to the conditions around the share price you set on an order to buy or sell. A limit buy order refers to the highest price you’re willing to pay for a share. Conversely, when selling, a limit order refers to the lowest price you’re willing to sell a share.

Limit orders are preferred when you want certainty about the price you could get when buying or selling.

Something to keep in mind with limit orders is that there may be other orders ahead of yours at the same or better price. The market clears orders based on ‘price-time priority’, which means those at a better price first, then by time submitted.

Understanding order types: what is an ‘at market order’?

When you buy, an ‘at market order’ means you’re willing to buy at the prevailing, available prices offered in the market.

When you sell, an ‘at market order’ means you’re willing to sell at the available prices bid in the market.

Since these orders place no limit on the price, they are often used to execute orders quickly, and when you’re happy to accept the going prices.

What is the difference between buying ASX and international shares?

The ASX is just one of the world’s many stock exchanges. The world of investing is not confined to the Australian stock market. After all, Australia represents only about 2% of the world’s investment opportunities.

So some investors may look overseas to gain exposure to sectors and themes not as well-represented in Australia. International shares may also aid the diversification of one’s portfolio.

But investing in international markets is not the same as investing in the ASX, and you should know the differences…and the risks.

For one, investing in overseas markets incurs currency risk. International shares are denominated in a currency other than the Aussie dollar, so the value of your investment may be affected by changes in currency exchange rates.

Since international shares are held by an international custodian, they are also subject to different political, economic, and regulatory changes.

You should also be careful to check any differences in taxes or brokerage commissions associated with lodging orders for international securities.

How many shares should I buy?

Generally, it’s suggested that you shouldn’t allocate any more than 5% of your portfolio to any one stock. If you allocate 5% of your portfolio to each stock, you’ll have 20 positions. For larger account balances, you could be aiming for 30–35 stocks in your portfolio, which means on average you’re looking at around 3% per stock.

Perhaps you might invest 5% in a larger-cap stock with secure earnings and low debt levels, and 1% in a smaller, riskier stock.

Whatever you decide, keeping your exposure to each stock small is a sensible way to diversify and control risk.

Are stocks and shares the same thing?

Shares and stocks are often used interchangeably to refer to the same asset class designating a stake in a business.

Shares are also known as securities or equities.

There are minor differences, however, in how we use the terms. For example, saying you own 100 shares is not the same as saying you own 100 stocks.

The former will be construed as referring to owning 100 shares in an individual company. The latter will be construed as owning shares in 100 different companies.

Are stock markets open on weekends?

No. The ASX opens at 10:00am and closes at 4:00pm, Monday to Friday.

While this is the moneymaking timeslot, there are also other ASX daily phases you may not have heard of.

The pre-opening phase takes place between 7:00am and 10:00am. During this time, brokers enter orders into ASX Trade in preparation for the trading ahead.

Orders are queued according to price-time priority and will not trade until the market opens.

The opening phase takes place at 10:00am and lasts for about 10 minutes. ASX Trade uses the timeslot to calculate opening prices.

The Closing Single Price Auction occurs between about 4:10pm and 4:12pm, where ASX Trade calculates stock’s closing prices.

Could the ASX stock market crash?

All markets have their ups and downs. While they generally tend to drift upwards, this is not an ironclad axiom. Crashes and corrections can — and do — happen.

As the quip goes, the four most dangerous words in investing are ‘this time it’s different’.

Each generation seems to have its own ‘this time it’s different’ moment.

As the Reserve Bank of Australia pointed out in a research note, railways, electricity, and the internet, for instance, are all transformational technological advances that ‘spawned great speculative excess.‘

Now, surprisingly (or not), Australia has had its share of speculative excess.

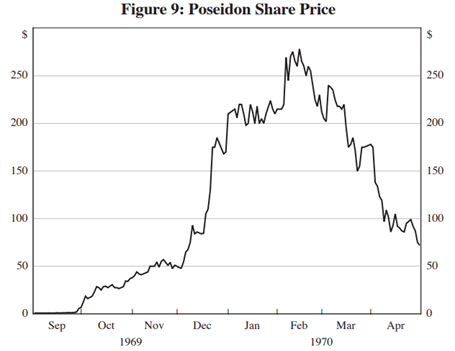

Let’s briefly examine Australia’s Poseidon bubble and crash as an example.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Australia’s mining sector was growing fast. Major new mineral discoveries were being made, like the Weipa bauxite mine, the Mary Kathleen uranium mine, the Mt Tom Price iron ore mine, and the Bass Strait oilfields.

Consequently, the ASX All Mining Index grew, on average, by 25% per annum over an 11-year span from 1958 to 1968.

Some investors may have started thinking this time it really was different.

Alas, it wasn’t.

In the mid-1960s, supply of nickel tightened. The free price of nickel hit a peak of £7,000 per tonne on the London market at the beginning of November 1969.

In the same year, Aussie miner Poseidon NL made a major nickel discovery in Western Australia.

As RBA’s John Simon reported:

‘Poseidon’s shares started rising around September 25, 1969 when results from drilling on the Windarra site became known to some insiders. Shares had been trading around $0.80 in early September and rose to $1.85 on Friday September 26. On Monday September 29 the company made a preliminary announcement that drilling had found nickel and this pushed the share price from $1.85 to $5.60. On October 1, company directors made a more detailed announcement indicating that they had a major nickel find. The share price jumped from $6.60 to $12.30 that day and then kept going up.‘

After such a steep rise, it seemed the frenzy would abate…until a frontpage story on Poseidon in the Australian Financial Review sent the stock’s price even higher.

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia

The allure of large gains led to the bidding up of other mining shares as speculators circled stocks with any association to nickel or leases near Windarra, where Poseidon’s claims were.

Emboldened by the seemingly inexorable run-up in price, analysts waded in with their share price targets.

In January 1970, for example, a UK brokerage released a report suggesting Poseidon’s value was between $300 and $382 per share.

As Simon noted:

‘While the run-up in Poseidon’s share price was spectacular, it was at least based on a real discovery. The speculative excess in the market is much more obvious in the behaviour of other mining shares. There were a large number of listings as promoters tried to cash in on the aura surrounding mining stocks. In an echo of the fabled ‘company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is’ from the South Sea bubble — a number of companies floated with ‘empty’ prospectuses containing no details on any prospects. Indeed, insiders managed to extract a lot of money from the boom. The AFR examined one group of promoters’ profits in a front-page article ‘How to turn $1 into $12m’.

‘Also, the mechanics of the market were such that buy orders could be made and payment not made for a couple of weeks. This encouraged people to buy on the prospect of making gains before any money was actually due, by which stage they could sell out for a large profit with no money down.‘

February 1970 marked the peak of Poseidon’s shares. Thereafter, the stock fell…and fell substantially.

At its height, Poseidon had a market capitalisation of $700 million, a third of the capitalisation of established giant BHP (then Australia’s largest company).

Remember, Poseidon reached that valuation while possessing only one mine.

While no discrete event triggered the fall, the buying frenzy that inflated fringe companies may have tarnished the whole market in many investor’s eyes.

The souring mood percolated to the financial pages, with negative articles appearing in the AFR.

After peaking at over 640 in January 1970, the ASX All Mining index fell to 200 in November 1971.

Concluding the (cautionary) tale, Simon wrote:

‘After the bursting of the bubble, Poseidon’s share price drifted down and the business of exploiting the Windarra discovery actually got underway. The mine produced nickel beginning in 1974 but it was not enough to keep Poseidon going. After experiencing many difficulties Poseidon delisted in 1976. The Windarra mine was taken over by Western Mining and operated until 1991 when it was shut down. This is in contrast to the majority of other stocks associated with the bubble — these never even had a viable mine, some didn’t even have mining leases.‘

Overcrowded public gallery at the Sydney Stock Exchange as Poseidon hits $214 a share.

Source: Australian Financial Review

Here are some great books on bubbles — and crashes:

- Charles P Kindleberger, Manias, panics and crashes: a history of financial crises

- Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

- David Chancellor, Devil take the hindmost: a history of financial speculation

Can the stock market be manipulated?

A recent review conducted by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) found Australia’s markets to be ‘generally of high quality and integrity‘.

Section 792A(a) of the Corporations Act confers on market licensees an obligation to ensure the market is fair, orderly, and transparent.

Additionally, confidence in the operation of companies on the ASX is reinforced by the whole-of-market regulation undertaken by ASIC, while the financial system stability is overseen by the Reserve Bank of Australia.

These regulatory bodies were set up to protect the integrity of the stock market and were given powers to act against misconduct threatening that integrity.

As former ASIC chairman Tony D’Aloisio commented:

‘Much of the underlying philosophy of the Corporations Act is based on the group of theories generally referred to as the ‘efficient markets hypothesis’. Markets are left to operate with a minimum of regulation.

‘However, two key regulatory underpinnings to the operation of the markets are disclosure (“let the sunlight in”) and prohibition of certain practices, most notably the insider trading and market manipulation offences.

‘It is not difficult to see why these prohibitions are needed. When investors have confidence in the integrity of our markets, the economic benefits can be significant and are generally well recognised (e.g. lower cost of capital). Conversely, the economic damage caused by offences such as insider trading and market manipulation can also be significant (e.g. higher cost of capital).‘

The pervasive system harms associated with permitting stock market manipulation is the reason why authorities strive hard to monitor and regulate it.

For instance, in a study of insider trading regulations in every country that had a stock market at the end of 1998, researchers in the United States found that 100% of the 23 developed countries studied and 80% of the 80 emerging markets studied had insider trading laws in place.

But laws themselves matter little without enforcement. A 2007 paper by Professor John Coffee found that a greater emphasis on enforcement helps to reduce information asymmetries.

Despite robust checks in place, regulators are always on the alert for new manifestations of market manipulation as technology evolves.

In 2015, ASIC released a report on the risks to market integrity posed by high-frequency trading and dark liquidity.

ASIC concluded the current levels of high-frequency trading and dark liquidity did not appear to adversely affect the function of markets or their ability to fulfil their role for the wider economy.

ASX news and analysis

You can discover the latest insights on global and Australian share markets right here at Fat Tail Daily, where we aim to offer deeper and more thought-provoking analysis than the cookie-cutter coverage you may find elsewhere.

To gain an edge, you must think at the edge. And that’s what our editors strive to do.

At Fat Tail Daily, we aim to provide you with insight you won’t get anywhere else, to help you stay ahead of the investing curve.

We’ll talk about the stuff that isn’t making any headlines, the stuff people don’t want to reveal.

With updates daily, you’ll always be up to speed with the latest moves of the stock market.

Source: ASIC

Source: ASIC