What is better: to try and fail, or fail to try?

Journalist Sebastian Mallaby posed this question in his study of venture capital firms.

Mallaby clearly slanted towards the trying and failing. Or, rather, he approvingly attributed the preference to VC firms.

Venture firms are comfortable with failure in the same way that basketball players are comfortable with misses.

It is part of the game.

Venture capital’s lesson in asymmetric returns

But in venture capital, unlike basketball, one made shot can make up for all the misses…and then some.

If Steph Curry misses 10 3-pointers and then makes the 11th, he’ll still have only scored three points.

If a VC firm invests $10 million each in 10 firms who all fail and then invests another $10 million in a firm whose value shoots up 100 times, the $100 million lost pales in significance to the $1 billion gained.

That’s the power law at work.

One success extinguishes one hundred failures.

Take internal research from investment firm Horsley Bridge. Horsley Bridge invested heavily in venture funds that backed 7,000 startups between 1985 and 2014.

5% of those investments generated 60% of Horsley Bridge’s total returns during the period.

Now that’s asymmetry.

Y Combinator — a well-known incubator of tech startups — estimated in 2012 that ~75% of its gains came from just two of the 280 firms it backed.

Just two.

No. That’s asymmetry.

The many failures seem almost necessary to the few successes. Swing hard enough for long enough and you’ll hit a home run…if a home run is what you’re after.

VC firms crave nothing more.

Swinging for the fences

The high failure rate of most of their bets necessitates swinging hard for big wins. An occasional two-bagger won’t pay for the dozens of duds and the overhead.

Venture firms swing hard, miss often, and sometimes strike it big.

And by big, I mean BIG.

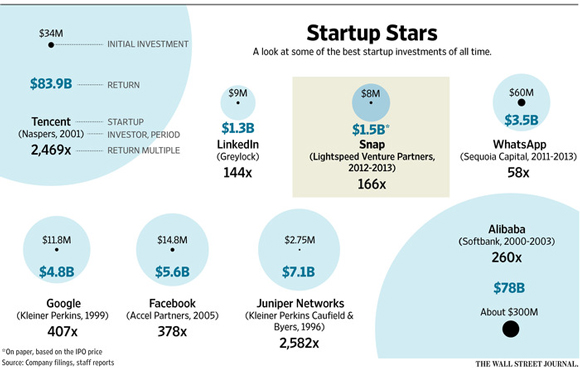

A few years ago, the Wall Street Journal listed some of the best startup investments of all time.

Venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins stands out.

In 1996, it invested US$2.5 million in Juniper Networks. The initial investment ballooned to a US$7.1 billion stake.

A 2,582-times return.

That windfall makes up for a lot of busts.

|

|

|

Source: Wall Street Journal |

Some might see in venture capital’s uneven distributions the presence not of a power law but of powerful luck.

‘If I had the capital to invest in 300 startups,’ they’ll say, ‘I reckon at least two will return enough to more than offset the losers.’

‘Give me a printout listing 1,000 tech startups and 300 darts and my portfolio will look just as good as any top VC firm,’ another naysayer chips in.

Mallaby has a great response. While VCs shoot for the stars, their ambition is bounded and calculated:

‘When today’s venture capitalists back flying cars or space tourism or artificial intelligence systems that write film scripts, they are following [the] power-law logic. Their job is to look over the horizon, to reach for high-risk, huge-reward possibilities that most people believe to be unreachable.

‘Of course, investing in what is categorically impossible is a waste of resources. But the more common error, the more human one, is to invest too timidly: to back obvious ideas that others can copy and from which, consequently, it will be hard to extract profits.’

Looking over the horizon

But how do you look over the horizon with eyesight keen enough to discern plausibility from fantasy?

Recognising and investing early in the Googles, Facebooks, Ali Babas and Junipers is hard.

Can you really do it without luck as the driving influence?

Take Accel Partners. In 2005, the VC’s investment principal Kevin Efrusy got tipped off by an intern at Stanford about a website then known as Thefacebook.

Efrusy was quick to act. But would Accel have been as quick without the fortuitous tip?

And take Kleiner Perkins.

Kleiner was skilled enough to see the rise of social networking. But instead of backing Facebook, it bet on Friendster and missed out on a generational return.

So, can you have an investment process that reliably tilts the odds in your favour?

Kobe Bryant once advised not to follow what the best do but how they do it.

Looking at how the best investors arrive at their picks is more edifying than knowing the picks themselves.

Mallaby alluded to part of the process earlier.

The best venture capitalists possess a powerful sight. The best investors, full stop, are great forecasters.

They have the future on speed dial.

Not the mundane and obvious future, grasped by most.

But the murky future most would consider too outlandish right now. A future most can’t even envisage.

It’s a safe bet tomorrow will be enough like today. But what about five years from now? Or 10?

Bill Gates once wrote that we overestimate what can be done in two years and underestimate what can be done in five.

The best investors don’t succumb to this underestimation.

They are perceptive enough to spot shifts early but creative and rigorous enough to figure out the logistics.

They spot where things are headed and hitch their wagon accordingly.

This foresight doesn’t have to be about trends. It can be about the nitty-gritty of particular businesses.

Legendary stock investor Julian Robertson — whose proteges are known as Tiger Cubs — said in an old interview his investment approach changed from the one he assumed at his career’s start.

His concept of value changed…and so did his view of what an analyst does:

‘When I started in the business and for a long time, my concept of value was absolute value in terms of a price-earnings ratio. But I would say my concept of value has changed to a more relative sense of valuation, based on the expected growth rate applied against the price of the stock. Something at 30x earnings growing at 25% per year — where I have confidence it will grow at that rate for some time — can be much cheaper than something at 7x earnings growing at 3%.

‘We’ve always had excellent analysts, and a good analyst is more adept at making judgments on growth. That’s their job. Based on the business and the company’ position in it, how fast is the company going to grow? It’s pretty hard to lose if you’re right on the growth rates when the growth rates are high. In that 30x-earnings company growing 25% per year, you’ll be bailed out pretty quickly because in about 2 1/2 years the earnings will double and the multiple on that is only 15x.’

To have confidence a business can grow for years to come requires a sound assessment of its future prospects, business landscape, and competition.

You cannot escape the importance of forecasting.

A contrarian streak is important, too.

Inherently, if you’re early on a theme or idea, the majority either does not share your view or your vehemence.

Vinod Kholsa — one of the world’s top venture capitalists — possesses just such a contrarian streak.

Here’s Mallaby again:

‘What really animated Khosla was the contrarianism he had exhibited in youth: Why did his parents go to the temple, why couldn’t he choose where to work and whom to love, why couldn’t everything be different? Venture capital was not merely a business; it was a mindset, a philosophy, a theory of progress.’

You have to seek out difference.

If you find yourself in deep agreement with the market, you are likely in possession of obvious ideas with slim outperformance potential.

Ask yourself, does my investment thesis differ to the consensus view?

What is your variant perception? What are you seeing that the market isn’t?

That’s where the big outperformance lies.

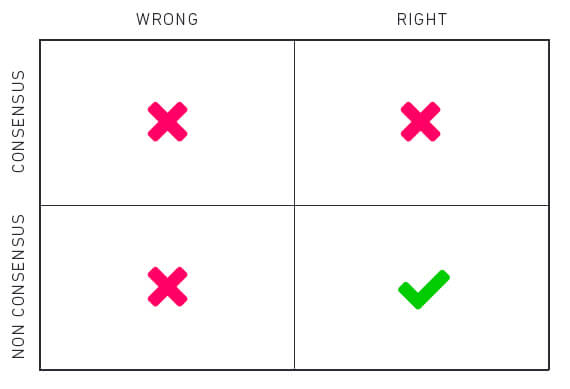

This is similar to Howard Marks’s performance matrix.

The best returns stem from being right and contrarian.

The average returns come from being right and consensus.

|

|

|

Source: Wealth Front |

Of course, the key here is being both non-consensus and right.

It’s not enough to conclude you can see what the market is yet to. Do the work to make sure you’re seeing straight.

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning