‘May you live in interesting times, is a sardonic curse with uncertain origin. Similarly uncertain is what the next decade might have in store for policymakers and participants in the financial system.’

This was the cheery opening of the RBA’s Assistant Governor this week as he evaded questions on the RBA’s reaction to recent inflation data.

The RBA board is set to meet over Melbourne Cup Day next week to decide the fate of interest rates for the rest of the year.

What was originally just AMP Bank forecasting a rate rise has now shifted to a consensus view among all the Big Four that rates will rise on Cup Day.

This includes Westpac’s Luci Ellis, who has taken the role of Chief Economist there after a six-year tenure as RBA Assistant Governor.

After years of working with Governor Michele Bullock, her insider perspective is considered a guiding light outside the RBA’s Ivory Tower.

Prior to the CPI data last Wednesday, she had maintained with conviction that there would be no more interest rate raises this year.

She even went so far as to boldly predict that ‘the next RBA rate move would be down‘ before the consumer price index (CPI) came out.

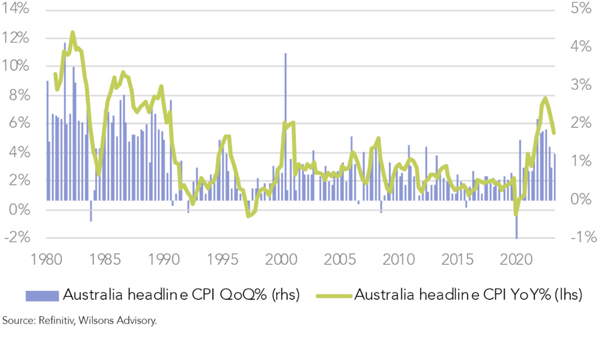

The latest CPI data showed headline inflation accelerated to 1.2% in the three months to September, from 0.8% in June.

| |

| Source: Wilsons Advisory |

Ellis backflipped after the results came out, saying she had ‘seen enough‘ to make her first call a rate hike.

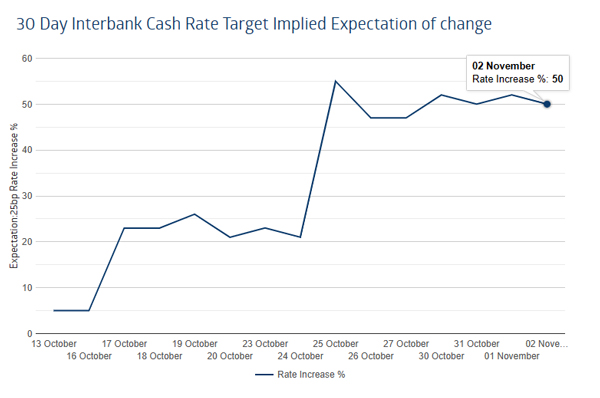

The markets agreed and moved from an implied 21% chance of a hike to a 55% chance overnight.

| |

| Source: ABS |

But with the market now placing the chances of a hike at 50/50, what’s our current situation?

The million-dollar question

Pundits have praised Michele Bullock’s communication style as a refreshing departure from the drudgery of typical central bank speeches.

Economists described her first speech as ‘assertive’ and ‘transparent’. In it, she maintained that she ‘will not hesitate to raise the [4.1%] cash rate further if there is a material revision to the outlook for inflation’.

So you may be thinking that the million-dollar question should be whether there was a material increase in the numbers.

For that, I would guide you over to economists far more capable than myself to analyse the full breadth of Australia’s inflation risks.

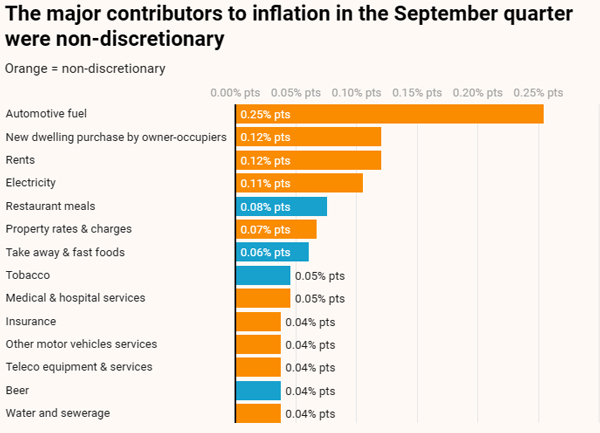

Simply put, fuel prices, house purchases and rent costs were some of the biggest factors adding to the inflation picture.

| |

| Source: Greg Jericho |

For what it’s worth an AFR survey conducted this week has 33 out of 35 surveyed economists predicting a rise to 4.35%.

But as the great Australian, Hugh Mackay once said:

‘Nothing is perfect. Life is messy. Relationships are complex. Outcomes are uncertain. People are irrational.’

For my dollars, I’d like to turn to the people actually making the decision.

Listening to Mrs Bullock at recent fireside chats and parliamentary meetings, she stated the CPI outcome was ‘pretty much as expected’.

For Mrs Bullock, her concern was less about the recent numbers. She remained worried about households getting acclimatised to fuel or rent prices continuing to climb.

She said it plainly enough:

‘[The] million-dollar question’ facing the central bank is how do people’s inflation expectations adjust to higher prices for common items such as petrol, food and rent.’

It is important to remember that the RBA’s concerns have a longer timeline than the media’s reactionary articles about fuel costs.

The RBA usually looks past fuel spikes when making its calls, treating them as a temporary setback.

And little-reported remarks by her have supported that idea.

Commenting in the Senate, Mrs Bullock said that the bank’s forecasts have inflation returning to the top of its target band by 2025.

Let’s consider the impact of fuel prices on this target.

Had fuel not jumped an astonishing 7.2% in just three months, the ABS annual inflation rate would have been closer to 5.1% rather than the 5.4% it hit.

This would have put inflation in line with their targets and kept price expectations from ‘de-anchoring’ in households over the long term.

So, the million-dollar question only seems challenged by a spike in oil prices that is rewinding.

Following the violent attack on Israel, the sudden spike in oil has since reversed and fallen by 9.4% over the past month.

So, what else is pressuring the call to raise rates next week?

He said, she said

The narrow path to a soft landing is looking ‘a little wider‘, Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy remarked at a Senate hearing last week.

‘I’m becoming more confident about our ability in Australia to maintain low unemployment rates and see inflation fall back within the band over a reasonable period,’ Kennedy said.

The Treasury wasn’t finished there. Treasurer Jim Chalmers added that he thought CPI numbers did not amount to a ‘material change in the inflation outlook.’

After these comments, the pile-on began. Economists and pundits decried the jawboning by the Treasury and called for the RBA to maintain its independence and raise rates.

As though rising interest rates and pushing more households to the brink was some game within the politics of bureaucracy.

He’s since walked back these comments, but not in time for another external party to weigh in on call next week.

The IMF released a statement on Tuesday with its own hot-take. In its report, the IMF said, ‘further policy actions are recommended to bring down inflation faster‘.

This is the same IMF that predicted in April 2021 that inflation would remain below the target range, being 1.7% in 2021 and 1.6% in 2022.

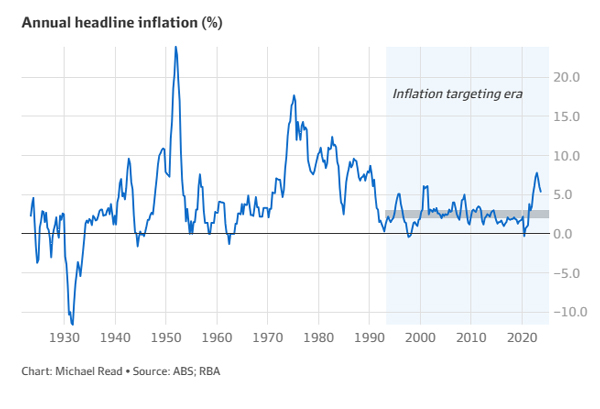

Inflation finally peaked at 7.8% in December of 2022.

| |

| Source: AFR-RBA |

Predictions are hard, remember your mistakes

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,’ Philosopher George Santayana once said.

For many in the media, the echo chamber of thoughts leaves little room for critical analysis.

Firstly, remember that many predictions and projections they base these calls on are often wrong. Just as they were wrong about an early recession in 2023.

The run-up to the Bank of England and Fed’s interest rate calls throughout the year revealed similar waves of thought. Many of them were wrong as they continued to keep rates on hold.

So, where does that leave Australian predictions?

For a more Australian view, it’s important to remember that we currently have the highest debt service costs in the developed world.

Thanks to a high number of variable mortgages in households and rate rises, the cost of mortgages has risen 114% since March last year.

Even if you discount the record-low rates during the pandemic, the cost of mortgages is now 70% higher than at the end of 2019.

Since then, wages have risen only 10.5%.

Consequently, Australians are buying less and quarterly CPI figures are still heading down.

This already painful squeeze will feel further pressure as the full effects of rate rises continue to trickle through.

This looks like a challenging time to push for further hikes.

So, will the RBA raise rates on Cup Day? Maybe, but don’t bet your house on it.

Regards,

|

Charlie Ormond,

Editor, Fat Tail Daily