Are you tired of reading about the energy transition yet?

I hope your threshold can withstand one more article.

Last week, I raised two points about the net zero push.

The first raised the idea of the world scaling back its net zero ambitions as politicians and voters bristle at the implied costs.

I quoted colleague Nick Hubble who said:

‘…almost all media coverage in Europe and the US is already highly critical of net zero. Even the politicians have woken up.’

The second point credited bureaucrats with enough intelligence to realise net zero requires a whole lot of materials.

That’s why Europe’s list of critical materials has doubled in the past decade.

I then concluded that the real issue — the crux of it all — is how the world plans to address the demand surge in critical metals everyone sees coming.

So let’s turn to that now.

Can we recycle our way to utopia?

You know it, I know it, everyone knows it — the world will need to do a lot of digging to source the manna for the electrified future.

Here’s the European Commission in 2020:

‘Growth in materials use, coupled with the environmental consequences of material extraction, processing and waste, is likely to increase the pressure on the resource bases of the planet’s economies and jeopardize gains in well-being.

‘Without addressing the resource implications of low-carbon technologies, there is a risk that shifting the burden of curbing emissions to other parts of the economic chain may simply cause new environmental and social problems, such as heavy metal pollution, habitat destruction, or resource depletion.’

Blunt and clear-eyed.

And here’s a recent White House whitepaper on the ‘transition risks’:

‘The transition to net-zero will affect the macroeconomy by changing capital markets, energy price levels and volatility, and labour allocation.

‘Recent work on the macroeconomic costs and financial risks of climate change has distinguished between orderly and disorderly energy transitions, with the latter defined by rapid changes in policy producing stranded energy assets or divergent policies across sectors.’

So what’s the solution?

Europe is big on recycling.

The European Commission thinks:

‘…circularity and recycling of raw materials from low-carbon technologies is an integral part of the transition to a climate-neutral economy’.

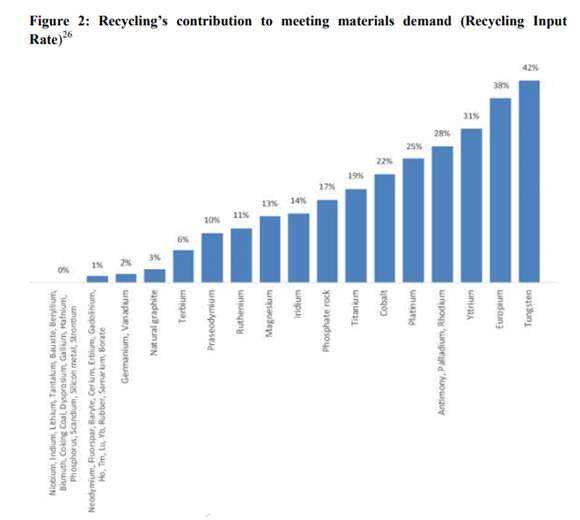

Europe already does a good job at reusing key inputs.

The continent recycles more than 50% of iron, zinc, and platinum — and that covers 25% of its consumption of those materials.

Not bad.

But clearly not enough at the current level and scope to meet the oncoming demand onslaught.

|

|

| Source: European Commission |

For instance, as the above chart shows, recycling’s contribution to meeting demand is negligible for key inputs like lithium, coking coal, silicon, borate, and natural graphite.

An interesting one is copper.

As James Cooper has rigorously pointed out here numerous times, copper is slated for a big supply deficit in his view.

But copper could also be a candidate for a recycling success story, given the metal’s capacity for reuse.

I have a resources economics textbook lying around. It’s actually very well-written! Anyway, in it, the author talks about copper recycling. Here’s an interesting snippet:

‘During 1910, recycled copper accounted for about 18% of the total production of refined copper in the US. Today, approximately 40% of the world’s copper demand today is met by recycling. And, according to the Bureau of International Recycling, an estimated 70% of the copper scrap exported by the US is used by industries in China. Other new metals being produced using recycled materials include aluminium, lead and zinc, with recycled materials of approximately 33%, 35%, and 30% respectively.’

Recycling is a great idea, but will it be enough?

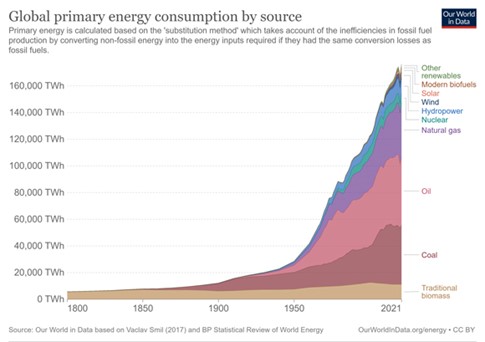

The sheer scale of the materials required to supplant fossil fuels with green energy sources is immense. Recycling won’t be enough on its own.

We’ll need to do some digging…and then some.

|

|

| Source: Our World in Data |

Can we dig our way to utopia?

But digging up critical materials is hard.

Even the European Union accepts this, writing in one report:

‘However, it is very difficult to bring new critical raw material projects to the operational stage quickly. This is partly due to the inherent risk and cost of new projects but is also attributable to the lack of incentives and financing for exploration, the length of national permitting procedures and the lack of public acceptance for mining in Europe.’

The inherent risk and cost of new projects are real.

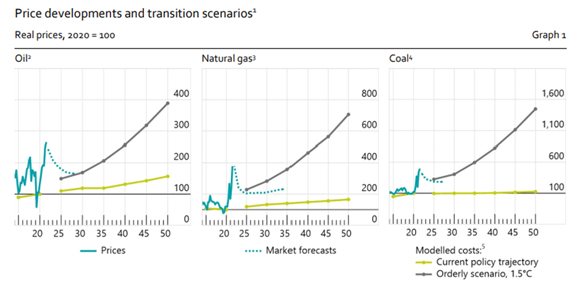

A 2022 report from the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (thankfully abbreviated as NGFS) pointed out:

‘The transition requires major investments in renewable electricity infrastructure and storage (about 40% more in investment each year on average in the net zero 2050 scenario than in the current policies scenario) but it also involves a decrease in investments in fossil fuel extraction and fossil fuel generated electricity (respectively minus 40% and minus 70% in the net zero 2050 scenario relative to the current policies scenario). Eventually, the success of a transition hinges on this capital reallocation…’

Counterintuitively, the success of the net zero transition depends on keeping the price of fossil fuels high to incentive substituting to renewables.

To achieve net zero, we must let fossil fuel producers enjoy record profit margins!

|

|

| Source: NGFS |

But do we even have enough critical metals in the ground to wean ourselves off fossil fuels?

A few months ago, Fat Tail Investment Research hosted an internal editor meeting. The Fat Tail brains trust convened in Melbourne to share their best ideas.

I was there when James cited research finding that, based on what we need to phase out fossil fuels entirely, global copper reserves fall short by 80%, global nickel reserves fall short by 90%, and global cobalt reserves fall short by 96%.

James thinks the world has not faced the potential for global energy shortages on the scale that’s likely to hit over the coming years.

What does it all mean for commodities?

So what does that mean for us as investors?

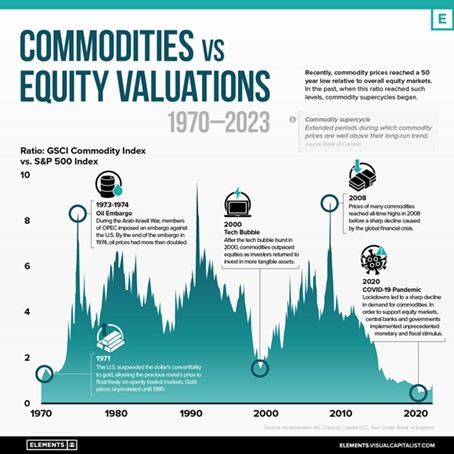

A few days ago, our Money Morning counterpart Ryan Dinse mentioned that commodities as a whole are ‘priced amazingly cheap compared to the stock market.’

He shared a great chart to illustrate:

|

|

| Source: Visual Capitalist |

In recent years commodities hit a 50-year low relative to equity markets.

For Ryan, ‘if you’re after good, long-term value, I’d say the Aussie market is the place to look’.

Just yesterday, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) CEO Daniel Westerman gave a speech outlining the tension between ‘today and tomorrow’:

‘The tension — between today and tomorrow — requires our industry to redesign and rebuild the aeroplane while we’re flying it. We need urgent investment. And we have to keep the lights on and the gas flowing today, while we assemble the new system of tomorrow, as the old system of yesterday gradually gives way.’

Whichever way you look at the energy transition issue, commodities come out ahead.

We need traditional commodities to keep the lights on today and the commodities of the future to keep the lights on tomorrow.

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Fat Tail Commodities

Comments