Predictions are useless. Most of the time.

At least, that’s what Jane McGonigal argued in her book Imaginable.

Predictions are often wrong. Like the prediction of a US recession in 2023.

And even when predictions are accurate, we often don’t know what to do with them.

What do you do with a prediction of a soft landing? The implications of that prediction are wide.

McGonigal instead calls us to replace predictions with ‘episodic future thinking.’ Imagine the world under different scenarios, like a sci-fi novelist.

Imagining the ins and outs of these scenarios is more fruitful than making bland, open-ended predictions.

In that spirit, here’s some imaginings about the advance of artificial intelligence. Charlie has touched on some wider themes in his piece earlier.

I’ll focus on the business of AI here.

Who will make money from AI? How profitable will the AI industry be?

Before that, an irony.

I was reading a book on the economics of AI. The authors’ key point was that AI will make predictions cheap.

Cheap and abundant. We’ll be in a prediction surplus.

How’s that for a prediction!

Cash is king, even for AI

Cash is king.

Markets look at any new development with cash in mind.

In the end, assets are discounted to the present value of their future expected cashflows.

This is a great model to have of how markets eventually appraise stocks…and technology.

So, for markets, the AI question is simple.

Where’s the money?

I agree with giant asset manager AllianceBernstein, whose recent dispatch on AI stressed the importance of profit:

‘Equity investors should look beyond the hype for companies with clear strategies to profitably monetize the benefits of generative AI.’

So how can you profitably monetise AI?

AI as better tool

The answer depends on what you think AI technology is.

We can categorise AI two ways:

A) AI lets businesses do something better (cheaper or quicker)

B) AI lets businesses do something entirely new

Does AI upend existing business models or execute them more efficiently?

Currently, the latter use of AI predominates. Two examples will suffice.

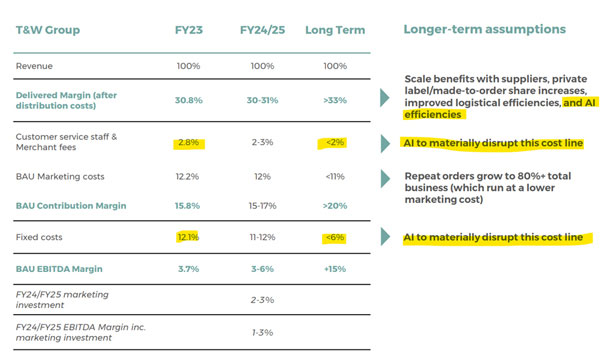

In late November, online furniture retailer Temple & Webster [ASX:TPW] touted how generative AI will lead to material cost savings for the company.

| |

| Source: Temple & Webster |

During the AGM, TPW’s chief executive Mark Coulter elaborated:

‘Our dedicated internal AI team is looking at how we implement AI tech across all of our customer interactions and internal processes. Early initiatives include using generative AI to power our presale product inquiry live chats. We’ve also used AI to enhance product descriptions across more than 200,000 products. This has led to an increase in conversion, products added to cart and revenue per visit.’

KMPG is turning to AI, too. Undoubtedly, so are its peers.

Last week, The Australian reported that the consulting giant launched its own internal chatbot — KymChat — six months ago.

KymChat exceeded expectations, ‘transforming the way the firm operates.’ Specifically:

‘Its KymChat — which uses Microsoft’s AI platform — has drafted advice to clients, accelerated research, ensured greater compliance with environmental, social and governance compliance, and been able to answer day-to-day staff queries, taking pressure off the KPMG’s HR team.’

Again, that focus on efficiency.

As currently imagined, AI synthesises knowledge and collapses the time it takes to execute it.

Instead of 50 billable hours to draft a legal document, it can take five.

Instead of a week assembling boilerplate code, it can take a day.

Instead of a customer waiting 60 minutes to talk to customer service, a chatbot talks to them at once.

The end products themselves don’t change. The efficiency and speed of their delivery do.

But how can investors analyse the impact on profit?

To whom do these efficiencies accrue the most?

To the KMPGs and the Temple & Websters? Or to the OpenAIs whose large language models (LLMs) they use?

KPMG will invest US$2 billion in AI over the next five years. In that span, it expects to generate US$12 billion in revenue from the AI technology.

A massive (forecasted) return on investment.

If those forecasts turn out accurate, the licensing fee KMPG pays to OpenAI is nothing compared to the benefits.

In that case, the users of AI seem to benefit most…

Unless the likes of OpenAI somehow take a cut.

That raises the issue of pricing.

A quick digression.

If KMPG can gain efficiencies by building a chatbot atop OpenAI’s platform, what’s stopping EY or Deloitte from doing the same?

Say a pharmaceutical company released a supplement making sports-related injuries 50% less likely. A team adding the supplements to its players’ diet won’t benefit competitively if all other teams do so, too. Their position relative to rivals won’t budge. Fans end up the real winners (and players).

AI at what price?

How can AI ‘platforms’ optimise the price?

A flat fee may prove too low if the benefits to users like KMPG are exponentially higher. Not to mention the AI platform’s costs serving KMPG’s needs.

That’s why firms like OpenAI have multiple pricing strategies.

I’m not just talking about premium ChatGPT.

OpenAI has enterprise agreements where big users — like KPMG — pay proportionate to use.

Specifically, OpenAI charges enterprise clients based on the tokens they use as inputs and outputs. Prices are per 1,000 tokens and 1,000 tokens are about 750 words.

OpenAI describes this as ‘simple and flexible.’ Clients ‘only pay for what [they] use.’

How much clients use OpenAI’s technology depends on the value derived from technology versus the price of that technology.

Users pay more if they get more.

But how much value do AI platforms like OpenAI provide over and above existing tools?

As AllianceBernstein put it:

‘A company that wants to increase the productivity of an employee making $100,000 a year by 25% faces a completely different value proposition if the AI technology for that employee costs $5,000 or $20,000. Therefore, at this stage of technology development, many investors are focused on how AI providers will price the technology.’

And the price of AI technology isn’t cheap if you’re paying for proportional use.

Refining and training AI models is expensive. Suitable microchips are expensive. And maintenance costs aren’t going down with scale.

Usually, software firms incur large expenses creating the software but spend almost nothing selling each additional unit.

Not so with generative AI.

Each additional query on its platform still incurs computational costs, whether it’s the first query or the billionth.

Last year, OpenAI reportedly lost US$540 million. It will be very telling what its bottom line is this year. Will its monetisation efforts offset its huge expenses?

AI as new tool entirely

All we’ve talked about so far is AI as better tool for existing uses.

Now let’s talk about AI as new tool for novel uses.

In Prediction Machines, economists Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb make this point:

‘Some AIs will affect the economics of a business so dramatically that they will no longer be used to simply enhance productivity in executing against the strategy; they will change the strategy itself.’

The Internet is a great example, and analogous to the advent of AI.

The Internet certainly made some existing things easier, but it also made some entirely new things possible.

This relates to a distinction Clayton Christensen made in The Innovator’s Dilemma between sustaining and disruptive technology:

‘What all sustaining technologies have in common is that they improve the performance of established products, along the dimensions of performance that mainstream customers in major markets have historically valued.

‘Disruptive technologies bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously. Generally, disruptive technologies underperform established products in mainstream markets. But they have other features that a few fringe (and generally new) customers value. Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller, and, frequently, more convenient to use.’

The problem lies with predicting AI’s disruptive — rather than sustaining — potential.

The ‘official birthday’ of the Internet as we know it is 1 January, 1983.

You could know then that the web was the future. But could you know what businesses would win out? What transformative use cases will emerge?

Could an investor in 1983 see Facebook coming? Or Google?

Predicting the disruptive products built with AI will be the hardest. We are still discovering this technology’s potential.

AI picks and shovels

Whatever technology it turns out to be — sustaining or disruptive — AI will need plenty of raw inputs either way.

So it’s no surprise the most obvious monetisation of AI has been the ‘picks and shovels’.

None more prominent that Nvidia.

Nvidia equips the leading AI companies with cutting-edge microchips, or graphics processing units (GPUs).

And with everyone rushing to ship AI products, everyone is hankering for Nvidia’s GPUs.

In the third quarter, Nvidia’s revenue topped US$18.1 billion, up 206% year on year. Next quarter, Nvidia expects sales to hit US$20 billion.

But Nvidia — and other chip makers like AMD — are not the only picks and shovels out there.

One sector overlooked by the market is cloud service providers.

AI applications require massive computational capacity and storage.

Big players like Amazon’s AWS, Microsoft’s Azure, and Google’s Cloud are reaping the benefits.

In the latest quarter, all three mentioned rising demand from AI for their cloud services.

Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella said:

‘Given our leadership position, we are seeing complete new project starts, which are AI projects. As you know, AI projects are not just about AI meters. They have lots of other cloud meters as well.’

Google’s chief Sundar Pichai said:

‘Today more than half of all funded generative AI startups are Google cloud customers.’

And Amazon’s boss Andy Jassy — who was pivotal in establishing AWS — said:

‘Our generative AI business is growing very, very quickly. Almost by any measure, it’s a pretty significant business for us already.’

Jassy said the likes of Adidas, Booking.com, Merck and United Airlines are building apps using AWS’s infrastructure.

But will these big players compete away each other’s profits?

Competition and AI

In the end, everything is a toaster.

So quipped Bruce Greenwald in Competition Demystified.

For full context, Greenwald said:

‘In the 1920s, RCA, manufacturing radios, was the premier high-tech company in the United States. But over time, the competitors caught up, and radios became no more esoteric to make than toasters. In the long run everything is a toaster, and toaster manufacturing is not known for its significant proprietary technology advantages, nor for high returns on investment.’

What will competition do for the AI industry and its profitability? Can something as complex as generative AI become…a toaster?

Some tech insiders already think so.

Earlier this year, SemiAnalysis published a leaked memo from a Google researcher who doubted Google had a moat in AI.

Here’s a snippet:

‘We’ve done a lot of looking over our shoulders at OpenAI. Who will cross the next milestone? What will the next move be? But the uncomfortable truth is, we aren’t positioned to win this arms race and neither is OpenAI. While we’ve been squabbling, a third faction has been quietly eating our lunch.

‘I’m talking, of course, about open source. Plainly put, they are lapping us. Things we consider ‘major open problems’ are solved and in people’s hands today. People will not pay for a restricted model when free, unrestricted alternatives are comparable in quality. We should consider where our value add really is.’

And just this week, The Verge reported that TikTok owner ByteDance is using OpenAI’s technology to build its own large language model (LLM).

This is against OpenAI and Microsoft’s terms of service.

ByteDance is the biggest culprit. But far from the only one. Here’s The Verge:

‘While it isn’t discussed in the open, using proprietary AI models — particularly OpenAI’s — to help build competing products has become common practice for smaller companies.

If the only barrier to entry is a rival’s terms of service, what does that say about the strength of that barrier?

A key question for the industry will be the level of commodification.

The more commoditised, the less competitive advantages. And, hence, less profits.

Investors appreciate technological innovation.

They appreciate expected cashflows more.

The question isn’t how much AI will disrupt.

It’s how much that disruption will pay and who will get paid the most.

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Analyst and host of What’s Not Priced In

Kiryll Prakapenka is a research analyst with a passion and focus on investigating the big trends in the investment market. Kiryll brings sound analytical skills to his work, courtesy of his Philosophy degree from the University of Melbourne. A student of legendary investors and their strategies, Kiryll likes to synthesise macroeconomic narratives with a keen understanding of the fundamentals behind companies. He’s the host of our weekly podcast What’s Not Priced In where he and a new guest week figure out the story (and risks and opportunities) the market is missing to give you an advantage. Follow via your preferred channel and check it out!

Comments