I’m going to be quite provocative today by taking two assets that can spark very heated discussions and putting them together.

No, this time cryptocurrencies are out of the discussion.

I’ll give you a clue.

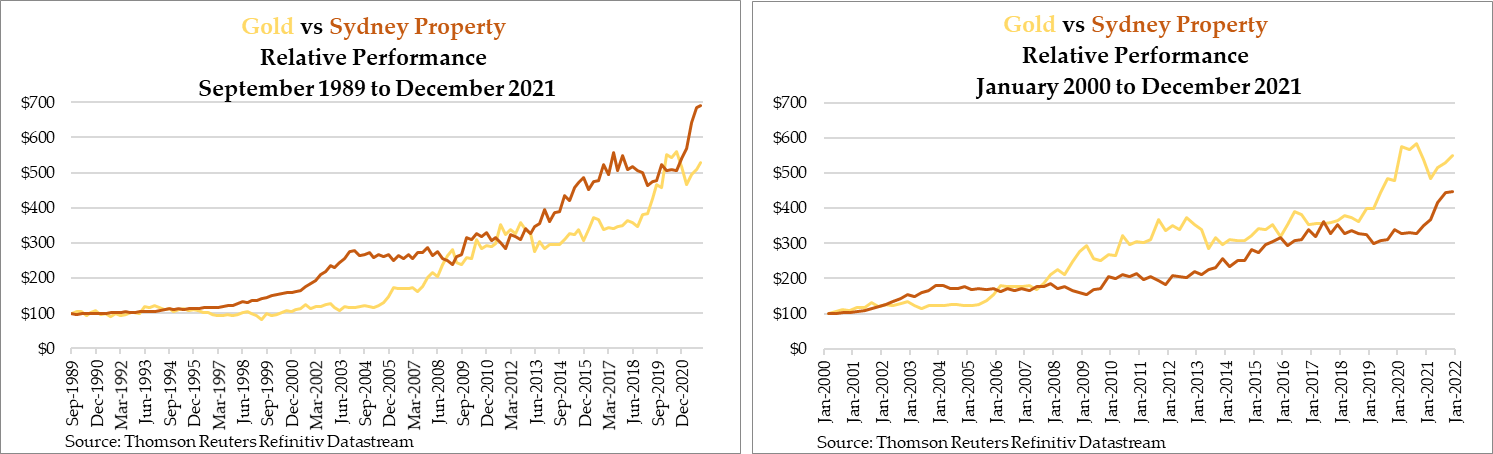

Both assets are tangible, and since 2000, an investment of $1,000 into one would give you $5,285, and the other would leave you with $4,465 at the end of last year.

Pretty neat, wouldn’t you agree?

It’s gold and real estate.

Now, why am I talking about these?

Because I have a gripe that I need to get off my chest.

The RBA, monetary policy, and inflation

Most of us know that the official role of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is to ensure that our economy is stable through monetary policy and to act as a backstop in case anything drastic happens to the financial system (such as a bank run, stock market collapse, etc.).

You know that the main tools that the RBA has at its disposal are setting the short-term interest rate and inflation targeting.

I’ve talked before about how the RBA isn’t doing the job it ought to. The idea that we need to have a central bank to regulate our financial system goes against the heart of the free market.

You can read about my reasoning in a back issue, here.

I’ve also talked about the problems of inflation targeting, whereby the RBA seeks to keep it at around 2–3% per annum when it implements monetary policy.

Firstly, the inflation rate is working off of past data. And the past data is usually subject to some smoothing and adjustments to the point that it hardly reflects reality. If you look at the official inflation rate on the RBA website, it’s reporting year-on-year inflation as of December 2021 is 3.5%. In other words, they’re saying prices of a typical basket of goods rose by 3.5% over the year.

I would beg to differ.

Note: We’re talking about December 2021, when oil was trading at US$76 a barrel. It was a fair chunk higher than at the beginning of the year, when it was US$48 a barrel.

Not to mention that we were seeing stores mark up prices due to trucker strikes and labour shortages.

I would hazard to say that the cost of goods and services rose no less than double the official statistics.

And don’t expect that this is just a one-off event either.

It appears that the RBA isn’t moving in the same direction as central banks around the world that are trying to rush and bring inflation under control with rate hikes. The RBA will likely sit back and try its luck on letting rising commodity prices take our economy along with the rising tide.

This brings about the issue of the biggest elephant in the room — housing affordability.

Housing affordability — an Australian dream no longer

One of the biggest criticisms that the RBA faces is its inability, unwillingness, or incompetence to deal with the housing affordability crisis.

A low interest rate encourages borrowing and causes a massive glut of currency flowing around in the economy. Much of Australian household debt is in housing, as Australians borrow to buy their own home or take advantage of the property boom to invest in real estate.

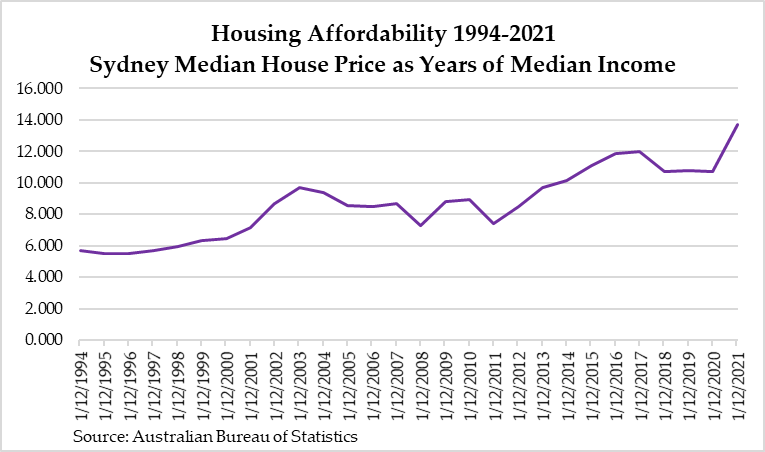

To determine how affordable property is, I’ve looked at the ratio between the median Sydney home and the median income in New South Wales from 1994–2021 in the figure below:

|

|

|

Source: ABS |

Note how properties are increasingly slipping out of reach of the average wage earner in Sydney as they need nearly 14 years of income to buy a property. Prices have risen almost 30% since the start of 2020 and now sit at $1.3 million, after being between $900,000 and $1 million from 2016–20.

Government stimulus, low interest rates, and Australian investors’ hunger for a stable investment yield have brought about this problem. And the negative impact it will have on society cannot be ignored.

For one, a housing affordability crisis can destabilise society as it causes intergenerational resentment.

The other big issue is debt. Repaying a massive mortgage exceeding $500,000 is no mean feat. Expect things to get worse when rates rise in Australia.

The RBA is not seeing that in the horizon just yet, but lenders are acting on it already.

The irony of an investment property

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not a property bear, nor am I against property investing (I admit that I used to be!).

But one thing I don’t get is why so many Australian investors think that investing in real estate is a stable and low-risk way to build wealth.

It has a lot to do with media advertising.

No one talks about gold like they talk about property.

But check out these two charts below showing how gold and property performed from 1989–2021 and 2000–21:

|

|

|

Source: Thomson Reuters Refinitiv Datastream |

You can see that the score is 1-1 between gold and property.

But there’s one thing I want you to keep in mind.

You don’t need to borrow to own some gold. With property, chances are you’ll need to borrow a bit.

I’m not here to say that you should ditch property and jump onto gold. After all, it’s hard to live inside a bar of gold, nor will people pay rent on your gold coins and bars.

I want you to consider things in perspective.

We’re facing a period of rising costs of living, increasing debt, and a possible market correction that could turn nasty very quickly. You want to be ahead rather than ending up getting fleeced when things come crashing down.

I believe properties will rise with inflation. But you have to hold enough equity to withstand the storm.

And here’s a twist.

I won’t spruik my wares this time. You’re well aware of them.

I have a colleague, Catherine Cashmore, who is a buyer’s agent and our resident property expert. She helps her readers avoid the pitfalls of real estate investing in her service, Cashmore’s Real Estate Wealth.

This is a great time to get some real advice, not from the ones who shill get-rich-quick property schemes in seminars.

I have read some of her work, and it has warmed my sentiment towards property investing.

God bless,

|

Brian Chu,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia