Another week, another lockdown, again. Australia is still stuck in COVID purgatory. And, with travel restrictions tightened too, it’s also in Sakoku — a reference to Japan’s attempt to shut itself off from foreign influence for more than 200 years. That stint left the nation badly backward, as will Australia’s leaky fortress policy.

But don’t worry; we have a central bank to save us. This week, the Reserve Bank announced it would…well…see if you can make sense of this lot, with my emphasis added:

Bloomberg:

‘Australia’s central bank took the first steps toward dialing [sic] back its emergency stimulus’.

Christopher Joye at Coolabah Capital:

‘The RBA is buying more securities on a relative basis, de facto increasing QE rather than holding it constant’.

And The Australian reckons the RBA is just ‘continuing QE measures’.

So, there you have it, less, more and the same, all in one QE announcement!

Only a central banker can pull that off.

The market’s reaction? Just as confused…

Bloomberg had ‘bond yields jump’ while the excellent MacroBusiness blog pointed out the opposite happened:

‘The media is full of the usual waffle today about tightening monetary policy, rises rates head. Blah, blah, blah.

‘Nothing could be further from the truth. The RBA committed a policy error yesterday that has been called out immediately by the bond market which is the only bourse that understands the sheer magnitude of the inflation challenge ahead.

‘The bond market reacted to the RBA by buying the very securities that, in theory, it should be selling. Long bond yields were belted as investors stampeded into the long-end of the curve, completely hosing RBA inflation hopes.’

I’m not going to untangle the confusion for you here. All of the above have it right, in their special way. The point is that everyone can make of central bank action and the market reaction whatever they will these days.

Especially the central bankers. So, it’s not just the market commentators and investors making it up as they go along. It’s also the policymakers who are doing more interpreting than being guided by numbers. This raises the potential for policy errors dramatically, in my view.

All this matters more than it has in the past too. Far more. The world has changed radically since the inflations, debt booms, and asset price bubbles we’re used to. Just as the Asian Financial Crisis was larger than the Savings and Loans crisis, the tech bubble was bigger than that. The 2008 crisis was bigger again, and the next crisis will be even larger. It’s known as the Everything Bubble for a reason.

We’re in far more debt, with far larger asset price bubbles, at far lower interest rates, with far more government intervention and far more moral hazard than before. Those are, of course, the consequences of papering over the previous crises with debt-financed bailouts, lower interest rates, and QE.

The size of the problem means the rules of thumb of the past, and the thresholds they gave us, don’t apply in the same way. We’re in uncharted waters, with only past wrecks to guide us.

There’s a big difference between a 1% interest rate increase when you owe $100,000 and $500,000. Given how much debt governments, companies, and homeowners are in today; the tiniest interest rate hike could threaten the vast debt loads we’ve built up.

Or just the threat of interest rate hikes, as we saw a few weeks ago when the Federal Reserve hinted at the vague possibility of interest rate increases years in the future…

Similarly, if inflation jumps from 1% to 2%, that’s a 100% increase. But 5% to 6% is just a small 20% jump. Even though the increase is the same, the effects on financial markets are very different.

Put the two together, and you have a level of fragility that we haven’t had before. What would’ve been small moves in the past would put the whole system at risk now.

We’re also more complacent. For two decades, we’ve had strangely low inflation. But that has lulled us into a false sense of security. A moderate increase in inflation will feel like a surge.

This is especially true in the bond market, where inflation is already outpacing yields, meaning investors agree to lose money in real terms. The Wolf Street blog ran the numbers on different types of bonds. But this paragraph was the best:

‘The average yield of B-rated bonds — “highly speculative” — dropped to a record low of 4.46%, or to a negative real yield of -0.53%. And the average yield of BB-rated bonds — “non-investment grade speculative” — dropped to a record low of 3.27%, or a negative real yield of -1.73%.’

People are losing money, adjusted for inflation, by investing in risky bonds…they will either lose money on defaults or inflation, in my view.

How to Survive Australia’s Biggest Recession in 90 Years. Download your free report and learn more.

One possible explanation for the poor real yields is that investors expect inflation to fall again. But what if it doesn’t? Or what if a return to deflation comes with the bond defaults that make risky corporate bonds risky?

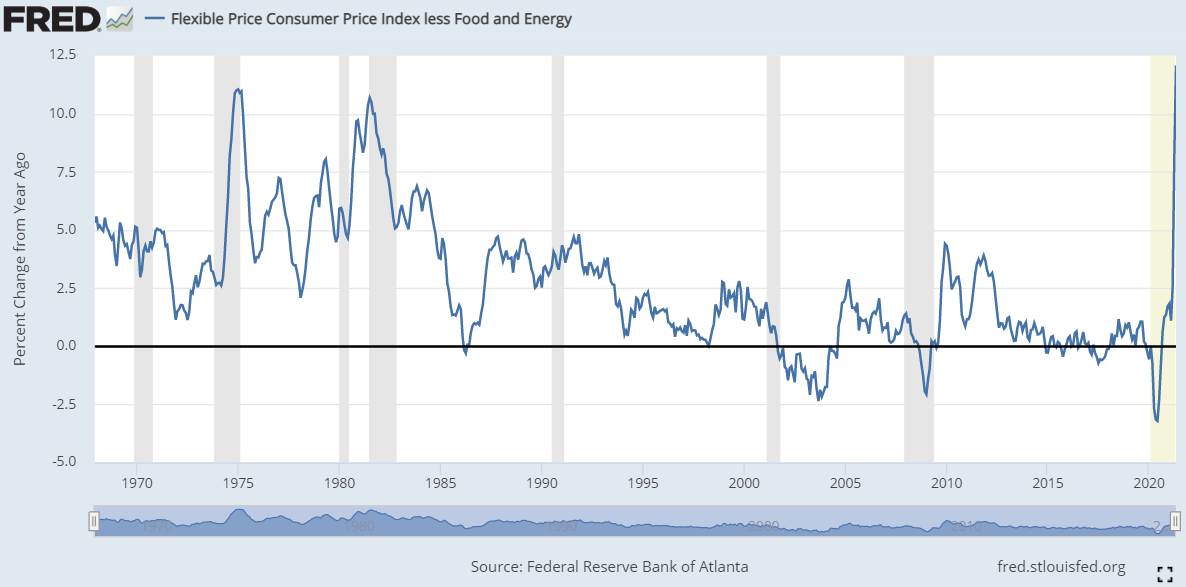

So far, the surge in inflation hasn’t been particularly modest, by some measures and in some places. Cantillon Consulting’s brilliant Twitter page pointed out that the Federal Reserve’s Flexible Price Consumer Price Index less Food and Energy measure is already above 1970s peaks…

|

|

| Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta |

Let’s turn back to debt again. What makes debt so interesting is that it has a binary outcome, while other investments and inflation do not. Debt is either defaulted upon or not — one or the other. You get paid, or you don’t.

This is what makes debt so dangerous. The risk is well hidden until it strikes all at once. It’s the old Ernest Hemingway joke:

‘How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.’

We’re still in the ‘gradually’ phase, but the direction is clear.

Inflation and stocks tend to rise and fall instead of having binary outcomes. The question is how far and how fast, not whether. That’s a very different set of risks…and opportunities.

It’s easier to boil a frog than the US central bankers did in the ‘70s than default on a frog’s government bonds. And so, central bankers prefer causing excess inflation over refusing to finance the government and forcing it to default, especially during a pandemic.

So, for investors, is it as simple as avoiding government bonds? Nope. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, adjusted for inflation, was at the same level in 1982 as 1916. When they tell you stocks go up in the long run, they really mean that the value of money evaporates over time.

Investing during inflation is very hard. And we’ve forgotten how to do it.

But what if central bankers really do raise interest rates, as they did in the ‘80s?

News.com.au recently did a good job explaining how a return to comparatively low interest rates ‘could mean interest repayments more than double in an instant’ for homeowners. What makes this so interesting is that persistently rising interest rates would be so unfamiliar to Australian borrowers and others worldwide.

‘Between 1970 and 1990 interest rate rises were an ever present threat to household budgets, with mortgage rates almost tripling from around 6 per cent to a peak of more than 17 per cent in 1990.

‘The next thirty years would bring almost the exact opposite.

‘Between 1990 and 2020, the RBA [Australia’s central bank] slashed interest rates time and time again, with rates falling from 17.5 per cent in January 1990 to sit at just 0.1 per cent today.

‘Rather than lying awake at night like their parents’ generation wondering if a rate rise would make their financial future all the more challenging, the atmosphere for the current generation of mortgage holders has been far more relaxed.

‘Instead of the threat of the RBA raising interest rates and forcing households to tighten their belts, in the past three decades the RBA has slashed interest rates every five months on average.’

For a generation of borrowers, the central bank has had its back. At every crisis, their mortgage became cheaper.

If that trend reverses and interest rates begin an upcycle because the next crisis is an inflationary one instead of a deflationary one, it’d come as an immense shock to borrowers who simply don’t know what a world under rising interest rates and inflation is like.

A lot of people are fond of pointing out that very few professionals in financial markets today know what it’s like to invest through an interest rate increase cycle. But the same goes for everyday people, let alone investors.

In The Guardian, Nouriel Roubini, who predicted the financial crisis, reckons our situation is a combination of the ‘70’s stagflation and a 2008-style debt-fuelled bubble:

‘We are thus left with the worst of both the stagflationary 1970s and the 2007-10 period. Debt ratios are much higher than in the 1970s, and a mix of loose economic policies and negative supply shocks threatens to fuel inflation rather than deflation, setting the stage for the mother of stagflationary debt crises over the next few years.’

Just remember, the worse it looks, the more likely an inflationary overdose becomes to try and paper over the problem. And, given the size of the problems this time, you can expect a lot of inflation will be needed.

Until next time,

|

Nickolai Hubble,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia Weekend

PS: Our publication The Daily Reckoning is a fantastic place to start your investment journey. We talk about the big trends driving the most innovative stocks on the ASX. Learn all about it here.