If we could harness the energy expanded writing about the energy transition, we would reside in a near utopia.

Energy transition, net zero, climate change, renewables, fossil fuels, green energy, decarbonisation…

The three Rs tell us to reuse, recycle, and reduce.

The above topics are certainly reused and recycled. If only our coverage of them was also reduced.

Or, at least, presented in a more insightful way.

We’re all aware the world is shifting to cleaner energy.

We can all agree that, where feasible, it is better to sustain living standards using cleaner energy.

Of course, the discussion often jams up over what exactly is feasible.

If we could maintain the same living standards using clean energy as we did using fossil fuels, why would anyone prefer sticking with the latter, coming as it does with externalities like pollution?

Pushing back, some will argue the transition to cleaner energy has its own costs and externalities.

The debate over the energy transition seems to boil down to a massive cost-benefit analysis.

Can we bear the costs of phasing out fossil fuels?

Are the benefits of renewable energy enough to offset fossil fuel divestment?

Some would interject, saying transition costs pale in significance to the costs meted out by climate change.

In that sense, no matter how expensive and inefficient the transition to net zero, so long as it’s achieved, it’s worth every penny and rising electricity bill.

This latter view implies a bifurcated conception of risks — physical risks and transitions risks.

Interestingly, it was incoming Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock, of all people, who elaborated on the partition of risks.

Reserve Bank weighs in on energy transition

Incoming Reserve Bank Governor Michele Bullock gave a speech last week on climate change and central banks.

Some might wonder how the two topics coalesce, but coalesce they do.

Bullock said both climate change itself and actions taken in response to it will have ‘broad-ranging implications for the economy, the financial system and society at large’.

Physical risks refer to the impact of ‘more frequent and extreme weather events’ and transition risks refer to ‘actions taken in response to climate change’, like policies, innovations, or even populace preferences.

Here are some other interesting quotes taken from her speech.

Bullock said the energy transition may put pressure on inflation:

‘The phase-out of carbon-intensive production may reduce aggregate supply temporarily. But investment in alternative production methods will boost aggregate demand. Depending on how this transition plays out, if the net effect is to temporarily lower aggregate supply, this would put upward pressure on inflation.’

On coal-fired power plant closures, Bullock said:

‘Coal-fired power plants are scheduled to be shut down over the next three decades. This could put upward pressure on energy prices if coal plant closures are not matched by renewables supply and storage. There is much uncertainty here.’

The Australian Energy Market Operator backed this up.

In its latest report, the AEMO said Australia’s national electricity market (NEM) is ‘subject to a large vulnerability to thermal fuel availability’.

Thermal fuel counts coal, oil, and gas as inputs.

AEMO further said that ‘maintaining the availability of thermal fuels for energy production throughout the energy transition will be essential for the reliability of the NEM’.

Back to Bullock, who said climate change may even affect the neutral interest rate, a lodestar for central bank policy:

‘The neutral interest rate is the interest rate at which monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary — and so it provides a conceptual benchmark for assessing the stance of policy. The impact of climate change on the neutral interest rate is not clear cut. In a world where significant climate risks materialise, households may be more likely to accumulate savings and firms may be less willing to invest, putting downward pressure on the neutral rate, and limiting the effective monetary policy space available to policymakers where interest rates are still positive. On the other hand, the extra investment required to replace capital stocks destroyed by more frequent natural disasters or to transition to a lower emissions economy could put upward pressure on the neutral rate.’

Uncertainty was the running theme of Bullock’s speech:

‘There is not only uncertainty around exactly how the climate will change but also around how this will affect the economy and financial system. In addition, it is unclear how the policies, preferences and technologies associated with climate mitigation will evolve.’

US President Harry Truman once requested a one-handed economist, an amputee incapable of complicating matters by adding ‘on the other hand’.

Bullock would have frustrated Truman even more. Her uncertainty and inferential temperance are so vast, no amount of hands could account for them.

But Bullock is not at fault.

Modelling physical risks of climate change is difficult. Assessing transition risks is, too, since it relies on estimating policy stances years from now.

What is the money saying?

Forget for a second the costs of the energy transition. What are the world’s energy producers focusing on while all the debates are raging?

Money talks.

So what is it saying?

If we look at the world’s biggest producers of fossil fuels, where are they spending money?

What future are they positioning for?

Let’s first consider coal producer Whitehaven Coal [ASX:WHC].

Whitehaven isn’t seeking to pivot away from coal, announcing a big capex spend for FY24. Management resolutely believes coal will remain an essential part of the energy mix.

In its FY22 report, the producer said this:

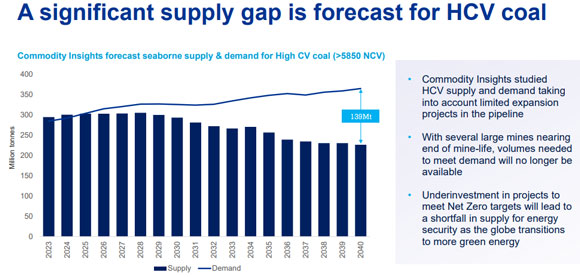

‘In the coming decade, metallurgical coal demand is expected to exceed supply due to depletion and closure of current mining operations compounded by the challenges of bringing new supply to market.’

|

|

|

Source: Whitehaven Coal |

And now from coal to oil.

Saudi Arabia’s Aramco, the world’s largest oil producer, isn’t looking to pivot away from its main revenue stream any time soon, either.

In fact, in 2022, Aramco embarked on what it called its ‘largest capital expenditure program ever’.

Aramco thinks the world’s ‘need for affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy will continue to grow, and we plan to grow our lower carbon intensity crude oil production with it’.

Aramco sees itself as the energy transition’s midwife:

‘Alternatives to traditional hydrocarbon-based energy sources are progressing, but, on their own, are not yet ready to meet the world’s energy demands and ensure a smooth energy transition. Oil demand is expected to grow for the rest of the decade and the world will likely continue to need oil and gas for the foreseeable future. With access to some of the world’s largest hydrocarbon resources, Aramco has a role to play in helping the world navigate towards a lower-carbon future.’

Some energy producers are embracing change more than others.

Take Origin Energy [ASX:ORG].

In its latest FY23 presentation, Origin said ‘renewables will meet an increasing share of energy needs’ but is also sticking with gas, believing gas will play a‘continued role in the energy mix’.

What it isn’t sticking with is coal.

Origin is exiting coal-fired generation and plans to retire its Eraring coal power plant — the largest in Australia — seven years early.

(Although the NSW government might have something to say about that.)

Origin wants the Eraring site to become a large-scale battery plant instead.

Last year, Origin’s CEO Frank Calabria said renewable energy is becoming ‘increasingly competitive’ with traditional sources:

‘Origin’s proposed exit from coal-fired generation reflects the continuing, rapid transition of the NEM as we move to cleaner sources of energy. Australia’s energy market today is very different to the one when Eraring was brought online in the early 1980s, and the reality is the economics of coal-fired power stations are being put under increasing, unsustainable pressure by cleaner and lower cost generation, including solar, wind and batteries.’

Finally, what about insurers?

Insurers have a lot to lose if climate change leads to more frequent adverse weather events they haven’t accounted for properly with higher premiums.

Take the latest half-year results from large insurer QBE Insurance [ASX:QBE]. The business dealt with what CEO Andrew Horton called a ‘number of poorly modelled perils’.

In response, QBE said it was changing its pricing to reflect the ‘changing nature of property catastrophe risk’.

This ability to raise premiums may be a profit boon for the insurance industry.

Economist Matthew Kahn, in his book Climatopolis, wrote:

‘Climate change will create big profit opportunities for insurance companies that are nimble enough to accurately price the real-time risk that policy owners (such as homeowners) face in different locations. We will adapt more easily with better geographical risk models and a greater tolerance for extreme price discrimination.’

For QBE, the insurer said in its FY23 report it does expect ‘climate change will increasingly impact the frequency and severity of weather-related natural catastrophes over the long-term’.

As a result, it’s purchasing more reinsurance…and raising premiums.

Other insurance firms are surely following suit.

Have markets priced in the right risks?

Clearly, the energy transition will be one of the most important trends for years to come.

But have the markets assessed all the risks?

What is the market not pricing in?

Australia’s potential era of energy poverty.

That’s what I discussed with Greg Canavan in the latest episode of What’s Not Priced In.

If you’re interested, do check it out!

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning