Last week, I ragged on earnings per share (EPS). Today, I want to be more constructive.

If we shouldn’t rely on EPS for valuation, what should we rely on? If not EPS, then what?

How about dividends?

Cash is fact, profit an opinion

Over three decades ago, economist Alfred Rappaport wrote the classic work Creating Shareholder Value.

In it, Rappaport punchily wrote that cash is a fact, and profit is an opinion.

Many since have propagated that message, including his future collaborator Michael Mauboussin.

(By the way, Mauboussin should get some honorary title for services rendered to the investment community for the bulging catalogue of free investment papers he’s published over the years.)

British economist John Kay was another, writing:

‘Most thoughtful analysts look at cash flow and assets rather than reported earnings when they try to assess the fundamental value of a business.’

So if cash is more informative than earnings, how can investors use cash flows to improve their stock analysis?

A hasty way is to overcome the unreliability of EPS by tethering earnings to cash flow. Anchor earnings to cash and see if you can spot any suspicious divergence.

As Kay again wrote:

‘Cash is a good reality check. A common feature of all the accounting wheezes…is that increased reported earnings have no cash counterpart. Tax is also a clue to what is really going on. Revenue authorities have many faults, but they do not often levy tax on profits that do not exist.’

High profits and a low tax charge may mean that profits are not what they seem.

We can go beyond using cash flows as a check on earnings, however. Cash flows can be used as the key inputs to value stocks.

Dividends as proxy for cash flows and value

If cash is a better measure than EPS, can we use dividends per share (DPS) as a proxy for cash flow?

We can certainly try. After all, what are dividends if not a company’s cash flow accruing to shareholders?

One way to value a stock using dividends is via the dividend discount model, which calculates the sum of the present value of all future expected dividends issued to shareholders.

John Kay is useful again here, expounding a simple way to use the model:

‘If 5% growth [of dividends] is the long-term average, there is a simplifying trick. Subtract 5%, the growth rate, from 8%, the discount rate [we can choose a different discount]. The difference, 3%, should be the dividend yield on the share.’

We can present this as a formula:

|

|

In the formula:

DPS = expected dividends per share a year from now

r = required rate of return/discount rate

g = stable, long-term growth rate in dividends in perpetuity

We can use Commonwealth Bank of Australia [ASX:CBA] as an example.

CBA’s FY24 DPS is expected to be $4.36 a share.

Using a discount rate of 8% and a stable dividends growth rate of 5%, we get a valuation of $145 a share, well overshooting the current price of around $101.

We can work backwards using the formula to figure out what the market’s implied stable dividends rate is.

|

|

Solving for g gets us a stable dividends growth rate as implied by the current market price of about 3.7%.

The pitfalls of dividends as valuation tool

The dividend discount model has great intuitive appeal. And it uses cash flows instead of earnings!

Surely, it’s the perfect measure of a stock’s value then, right?

Unfortunately, nothing is so straightforward in investing.

The model has its downsides.

One of the biggest is the sensitivity to assumptions. Tweak the key inputs and the valuation swings wildly.

We saw that briefly with the CommBank example.

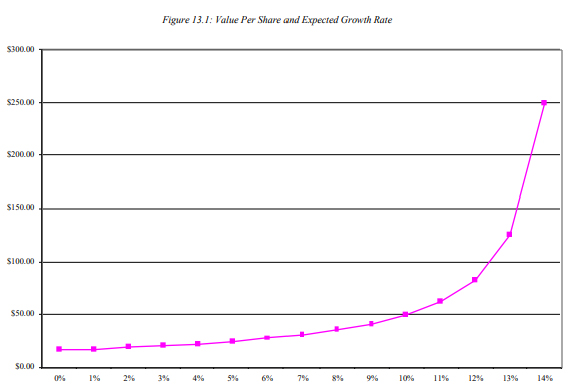

Finance professor Aswath Damodaran further explains in his valuation textbook:

‘The model is a simple and convenient way of valuing stocks but it is extremely sensitive to the inputs for the growth rate. Used incorrectly, it can yield misleading or even absurd results, since, as the growth rate converges on the discount rate, the value goes to infinity. Consider a stock, with an expected dividend per share next period of $2.50, a cost of equity of 15%, and an expected growth rate of 5% forever. The value of this stock is $25.00. Note, however, the sensitivity of this value to estimates of the growth rate.

‘As the growth rate approaches the cost of equity, the value per share approaches infinity. If the growth rate exceeds the cost of equity, the value per share becomes negative.’

Damodaran then shared this very good chart to illustrate the model’s hypersensitivity:

|

|

|

Source: Damodaran |

The model is intuitive and uses cash flows as inputs. But it cannot escape the perils of relying on assumptions.

The analyst’s plight — no shortcuts in sight

Investors must resist the temptation to seek shortcuts and analytical paths of least resistance.

Quickly checking the EPS is easy, but is it worthwhile?

Not really.

Investing is a competitive game where the shortcuts lead to nowhere but average returns…or worse.

Martin Fridson put it best in his magnus opus, Financial Statement Analysis (emphasis added):

‘Financial reporting occurs in an institutional context that obliges conscientious analysts to go many steps beyond conventional calculation of financial ratios. Without the extra vigilance…the user of financial statements will become mired in a system that provides excessively simple answers to complex questions.’

Six income stocks that could grow and pay dividends

I’ve talked a lot about dividends today, but I’m no expert. You know who is?

Greg Canavan.

Greg’s a deep value guy. He loves to find stocks trading below fair value.

He also appreciates the attractiveness of divvies.

Instead of speaking for him, I’ll let Greg speak for himself. Here’s an excerpt from his latest dispatch for The Insider:

‘There is an income/growth sweet spot developing in the market right now. It’s giving you the opportunity for a juicy dividend yield AND growth.

‘While the ASX 200 might be flat over the past two years, there are plenty of stocks that are down significantly from their highs.

‘In many cases, these stocks offer prospective dividend yields well above the cash rate AND trade significantly below a reasonable estimate of intrinsic value.

‘The way I see it, you can get a decent yield while waiting for the tightening cycle to play out. Then you’re in a good position to benefit from the eventual tailwind of a post-recession/slowdown easing cycle.

‘All this is to say that if you just focus on the yield and not the price you’re paying for that yield, you’ll get into trouble. Especially in a market where more profit headwinds are likely, as the lagged impact of previous monetary tightening works its way through the economy.’

Greg’s just written a report detailing his top dividend picks on the ASX right now.

These six stocks highlight Greg’s contrarian value approach, because you won’t find many of them in fusty traditional income portfolios.

That’s because Greg’s picks were about deep value first, income second.

You can now read the report, for free, here. Enjoy!

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning