Most of the talk this week concerned US inflation falling and its implications. The market was quick to price in the news. Stocks climbed, and economists argued over the longer-term implications.

Ultimately, the story boils down to the same thing you’ve heard before. The lower CPI numbers could move the needle at the Fed for future rate rises. But it’s too early to tell.

‘It’s still premature to call the inflation fight over,’ said Will Compernolle, a macro strategist at FHN.

‘The biggest contributors to October disinflation, falling energy, core goods prices and decelerating shelter inflation are all the outer layers of the Fed’s “inflation onion” that won’t contribute to disinflation forever.’

It’s a bit hard for investors to make investment decisions based on the macro environment when it comes down to the inner thoughts of those at the Fed.

So I thought I should zig while everyone else zags.

Today, we’ll take a closer look at China. I’ll provide some background to the Chinese property crisis and take the pulse of the world’s second-largest economy.

Why should you care?

China is Australia’s largest two-way trading partner, accounting for almost a third of our global exports. That’s about as large as the next four trading partners combined.

It’s easy to dismiss China; we’ve all heard of the failure of the post-lockdown economy and its ageing population.

But it’s worth understanding China and how its economy fell into its current state.

Let’s take a little tour.

Structural issues

China’s ailing property market has been in a slow meltdown for the past two years. But the seeds of its downfall started long before.

The property boom began in 1998 when China allowed households to buy and sell apartments. This came at the same time as mass migration from the country to the cities. Local governments were suddenly making huge sums from land sales.

Skyscrapers and infrastructure grew at a blistering pace. They were often supported by local government policies to promote homeownership.

The Chinese believed that housing was a safe and profitable market. Money flowed into housing from every direction, and property developers blossomed.

Giant developers grew their market share from 26% to over 60% through the 2010s. They funded this growth by aggressively borrowing from a shadow banking system. This system used tangled avenues of trusts and loan guarantees from often corrupt local officials to back projects.

The state turned a blind eye to the shadow banks. They provided an easy channel for stimulus after the GFC that didn’t require any tinkering with its highly regulated banks. Local governments were able to fund vanity projects to please their central masters.

For developers, these shadow banks provided access to highly leveraged loans. Developers put up very little money and took out eye-wateringly large loans.

Property prices surged over six times in 15 years and, at its peak, contributed 25% of China’s GDP in 2020.

Property accounted for 70% of Chinese household wealth. Some married couples divorced on paper to avoid the local property ownership restrictions and buy again. Homeownership reached one of the highest rates in the world at 90%.

All were in awe of China’s blistering GDP growth, which averaged 7.7% from 2010–19.

The First sign of trouble

The problems had been stewing for years but were papered over by the rampant growth of house prices.

Decades of infrastructure and real estate investments had exhausted the backlog of highly productive projects. Any new projects were now dragging down the economy.

Houses were often built using counterfeit or low-quality products with corners cut. Known by locals as ‘tofu-dregs‘, these houses personified the Chinese property sector.

Xi had known about these issues for years but had been reluctant to touch the growth levers. As long as property prices went up, there was little pressure to fix the problem.

Prices rose to levels that made cities unaffordable for average workers—forcing a response from the communist old guard.

‘Houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation,’ Xi grumbled in his 19th Party Congress address.

Eventually, the Xi government put forward the ‘three red lines‘ regulation to clamp down on this rampant speculation. These limited the levels of debt developers could accrue.

These changes coincided with the pandemic and lockdowns, bringing construction to a standstill.

As the pandemic raged, demand for new housing plummeted, and the massive oversupply became evident.

House prices began to fall, and ghost cities became a hot topic for Chinese locked down in their homes.

| |

| Source: Architecture Digest |

Pictures like this emerged, showing farmers moving back into land bought off them and then left abandoned.

The prominent developer’s balance sheets couldn’t handle the early property downturn. The ‘three red lines’ blocked big companies like Evergrande from taking out new loans.

Evergrande defaulted on its first loan in 2021, and fear spread faster than the virus.

Chinese officials have hidden the full scale of the meltdown. The data shared uses indexes and samples rather than direct house prices like other countries.

This opens up ambiguity and ‘data massaging’, something China is well known for.

Even so, the data from China still shows a property sector in crisis.

| |

| Source: Axios Visuals |

Estimates of the number of vacant homes and apartments are between 65–80 million units.

Developers Country Garden and Evergrande have faced defaults and losses of US$6.7 billion.

Chinese property developer stocks have collapsed, losing $56 billion in value.

For economists, it raises serious questions about the country’s prospects.

‘The key question now remains what can replace the property sector as a growth engine for the Chinese economy over the medium term, if not right away,’ wrote economist Miao Ouyang.

The masters in Beijing felt the same way.

China’s stimulus arrives

After weak signals and promises by Chinese officials in the past year, the country’s leaders have come out swinging.

President Xi recently stepped out from behind the curtain and made a surprise visit to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). This was the first Chinese head since Mao Zedong to stride into the Central Bank’s halls.

Like most things in Chinese politics, the visit was more theatre than substance. But the move signalled that Beijing was waking up and taking steps to address the ailing economy.

After the visit, the PBOC issued 1 trillion yuan (AU$212 billion) in sovereign debt in the fourth quarter. The extra debt would focus on ‘urban village restoration and subsidised housing projects,’ according to bank officials.

Dubbed ‘helicopter money’, this money adds to previous large cash injections. The plan involves giving cash to owners for demolishing their old shanty town homes and rebuilding new ones.

‘This is not to spur growth but rather deliver a more balanced development for the longer term,’ said Bruce Pang, chief economist for Greater China at Jones Lang LaSalle.

For a central planner, that may sound balanced. But to us, it looks like a new way to inflate the value of houses in less developed cities and start the cycle again.

The Central Bank also raised the budget deficit ratio above its long-adhered 3% limit to 3.8% of GDP.

All of this is to try to spur growth. China has set an annual growth target of around 5% for 2023.

The other goal is to try to get the cautious public spending again. Early signs point to some improvement here.

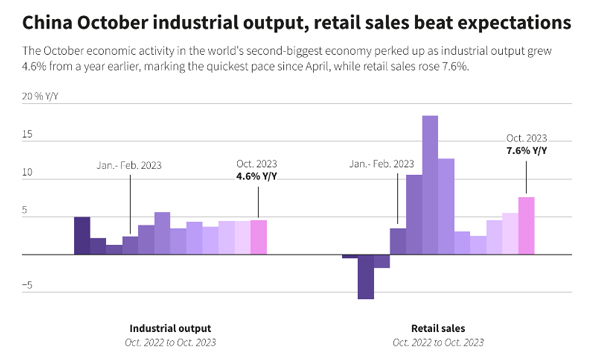

| |

| Source: Reuters |

Retail sales and industrial output beat expectations in October but are still starting from a low baseline.

China has a long road to meaningful recovery. The centralised powers of the nation could inevitably lead it down another path of mismanagement. But in contrast, the vast powers that the state holds could give it the ability to change tack rapidly.

Unfortunately, for now, the stimulus is mainly focused towards construction. If China wants to improve meaningfully, it must fund productive sectors rather than rewinding the cycle to go again.

Regards,

|

Charlie Ormond,

For Fat Tail Daily

Comments