China’s economic headwinds can be summed up in three words — debt, demographics, and decoupling.

There’s substantial empirical evidence that national debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 90% result in slower growth. Whatever stimulus might have arisen from deficit spending at lower debt-to-GDP ratios begins to fade at a ratio of 60% and completely reverses at 90% or higher.

In plain English, you can’t borrow your way out of a debt trap.

Calculating the debt numerator of the ratio is difficult in China because there’s little or no distinction between government debt and private debt.

Many of the largest corporations in China are State-owned enterprises (SOEs), State-controlled banks, or ostensibly private companies, such as Huawei, that are regarded as ‘national champions’ and overseen by Communist Party minders and sympathetic oligarchs.

Much government debt is not incurred at the national level but at the provincial level through opaque methods, including subsidies to local real estate developers.

On balance, it’s reasonable to combine all this debt for purposes of a debt-to-GDP ratio since the central government and Communist Party stand behind almost all of it.

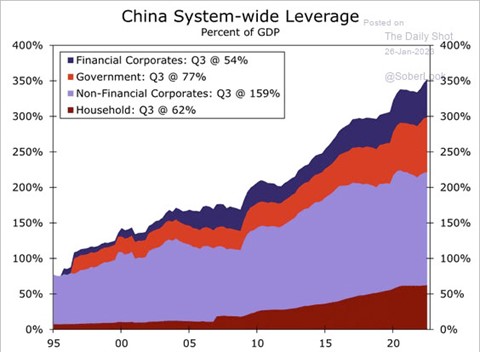

The result is a debt-to-GDP ratio of about 350%, as shown in the graph below:

|

|

| In China, the distinction between government debt and corporate debt is not meaningful because most companies are State-owned enterprises, State-controlled banks, or nominally independent companies that are de facto under State control as ‘national champions’. The combined debt at 350% of GDP is demonstrably a major drag on growth. China cannot borrow its way out of a debt trap. Source: IIF and Wells Fargo Economics |

At ratio levels of 30–60%, an additional dollar (or yuan) of debt might produce $1.25 or more in output, assuming it’s used productively. As the ratio reaches 90%, the output from a dollar of debt approaches $1.00. Beyond 90%, the output from a dollar of debt might be only 90 cents or less.

In other words, the numerator (debt) goes up by $1.00, but the denominator (GDP) goes up by 90 cents. This means the debt-to-GDP ratio gets worse.

This problem is exacerbated in China because much of the debt is not spent productively.

I have visited construction projects in the countryside of China where entire cities visible to the horizon were being built from the ground up. Along with the cities were airports, highways, golf courses, convention centres, and other amenities.

It was all empty. None of the buildings were occupied except by a handful of show tenants. Promises of future tenants rang hollow. The construction did create jobs and the purchasing of materials for a few years, but the debt-financed infrastructure was completely wasted.

The only ways out of a debt trap of the kind China have constructed are default, debt restructuring, or inflation. The last two are just different kinds of default.

The situation doesn’t necessarily resolve itself quickly. The debt burden can persist for years. Just don’t expect robust growth while it persists.

Demographic disaster awaits

China’s demographic disaster is something we’ve written about extensively in the past.

To summarise, China’s birth rate is now below what is called the replacement rate. That rate is 2.1 children per couple. (The reason the number is 2.1 and not 2.0 is to make allowance for deaths before the age of childbearing.)

The replacement rate is the number of births needed to maintain a population at a constant level. Birth rates in excess of 2.1 will increase the population; birth rates below that level will shrink it. China’s current rate is reportedly about 1.6, but some analysts say the actual rate is 1.0 or even lower.

At that rate, China’s population will shrink from 1.4 billion to about 800 million in the next 70 years. That’s a loss of 600 million people in a single lifetime.

There are many ways to express GDP growth mathematically, but the simplest is to multiply the working population by productivity per worker.

Productivity growth has been lagging in almost all economies for reasons economists do not completely understand. If you assume productivity will remain constant (a reasonable assumption if China fails the high-tech transition) and the population drops by 40%, then it follows the economy will shrink by 40% or more.

That’s not slow growth. That’s the greatest economic collapse in the history of the world.

Growth could drop even more because China’s population is not only shrinking, it’s aging.

Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and cognitive decline are all highly correlated with age. In the not-so-distant future, China will have hundreds of millions of nonagenarians and centenarians who will require almost full-time care. Not only will the sufferers be non-productive, but the working-age caregivers will also be doing critical work with little potential for productivity gains.

Of course, the slowing, and now negative, growth in China’s population is partly the bitter fruit of China’s misguided ‘one-child policy’ from 1980–2016 (in which millions of newborn girls were drowned at birth because the families preferred boys). China has now reversed that policy and is encouraging larger families.

That appeal will fail because a combination of more educated young women, more urban residents, and greater career choices will cause women to defer marriage and resist having children despite government incentives.

China faces many economic headwinds, but this demographic disaster is more of a Category Five hurricane. China’s economy will not be out from under this burden for 100 years, and possibly never.

Decoupling? Try divorce…

The final headwind is the world-historic decoupling of China from many developed economies, principally the US.

The decoupling of the world’s two largest economies is a momentous development that bodes ill for both economies, even though there may be good geopolitical reasons for the US to delink from the Communists.

What’s striking is that the decoupling is mutual — Chairman Xi seems as eager to reverse close investment linkages with the US as the US is from China.

The US and China will never be completely isolated from each other. A new equilibrium will be reached. Still, this equilibrium may consist of the US purchasing low-tech manufactured goods from China while China buys agricultural produce and energy from the US.

High-tech exports and imports will be curtailed, and US direct foreign investment will seek new homes in Vietnam, Malaysia, and India, among other markets.

The geopolitical aspects of this are vast and are not explored at length in this article. Yet, the economic aspects are clear and undeniable — slower growth for China.

All the best,

|

Jim Rickards,

Strategist, The Daily Reckoning Australia

This content was originally published by Jim Rickards’ Strategic Intelligence Australia, a financial advisory newsletter designed to help you protect your wealth and potentially profit from unseen world events. Learn more here.