What goes up, must come down.

Or not.

Sometimes the laws of physics don’t seem to apply to certain stocks.

If you are a fundamental investor the old adage is ‘buy low, sell high’.

If you are a technical investor, the saying could be ‘buy high, sell higher’.

Either way you go about things, certain stocks are starting to look like they can defy gravity.

In today’s piece I’m going to take a closer look at the immense gains from BNPL stocks, pivot to a discussion of the Amazon.com, Inc [NASDAQ:AMZN] share price for context, and look at potential long-term risks.

Four Well-Positioned Small-Cap Stocks: These innovative Aussie companies are well placed to capitalise on post-lockdown megatrends. Click here to learn more.

Everyone piled in, but how to know when to get out while the goings good?

Afterpay Ltd [ASX:APT] is the poster child, but many of the smaller accomplices in the BNPL sector are clocking even more explosive numbers.

Sezzle Inc [ASX:SZL] stands out, as well as Zip Co Ltd [ASX:Z1P] and Splitit Payments Ltd [ASX:SPT].

In a standard market environment, these companies would all be considered competitors.

But that assumes a more bounded market.

With any new technology or innovation, the market expands.

Meaning these companies aren’t so much competitors bumping into each other, as they are operating in parallel in a rapidly expanding market.

If you look at it this way, the gains in the BNPL space make more sense.

And with Goldman Sachs tipping APT to grow its customer numbers by nearly fivefold over the next decade, the word is well and truly out.

Everyone piled in. When you have your Uber driver saying he is buying APT shares, there could be a bubble on your hands.

Call it the contrarian Uber driver portfolio analysis signal!

Regardless of the Uber driver’s assessment, analysts are torn on APT’s prospects.

How do you put a price target on a company that could be anything?

With companies that are not yet profitable, looking at the price to sales ratio is one option.

But the more intriguing question is, when’s a good time to get out?

It’s not a gain until you sell

I recently had an old friend ring me up complaining to me that he never knows when to get out of a stock, especially when it’s up heaps.

I said bluntly, ‘Always remember, it’s not a gain until you sell!’

It’s so simple.

Greed often keeps people from exiting when they should.

Setting a stop-loss is one way to mitigate your greed.

There’s an important caveat here.

Namely, if you are targeting stocks with exponential potential then you can get stopped out of immense share price runs far too early.

Amazon is case in point here.

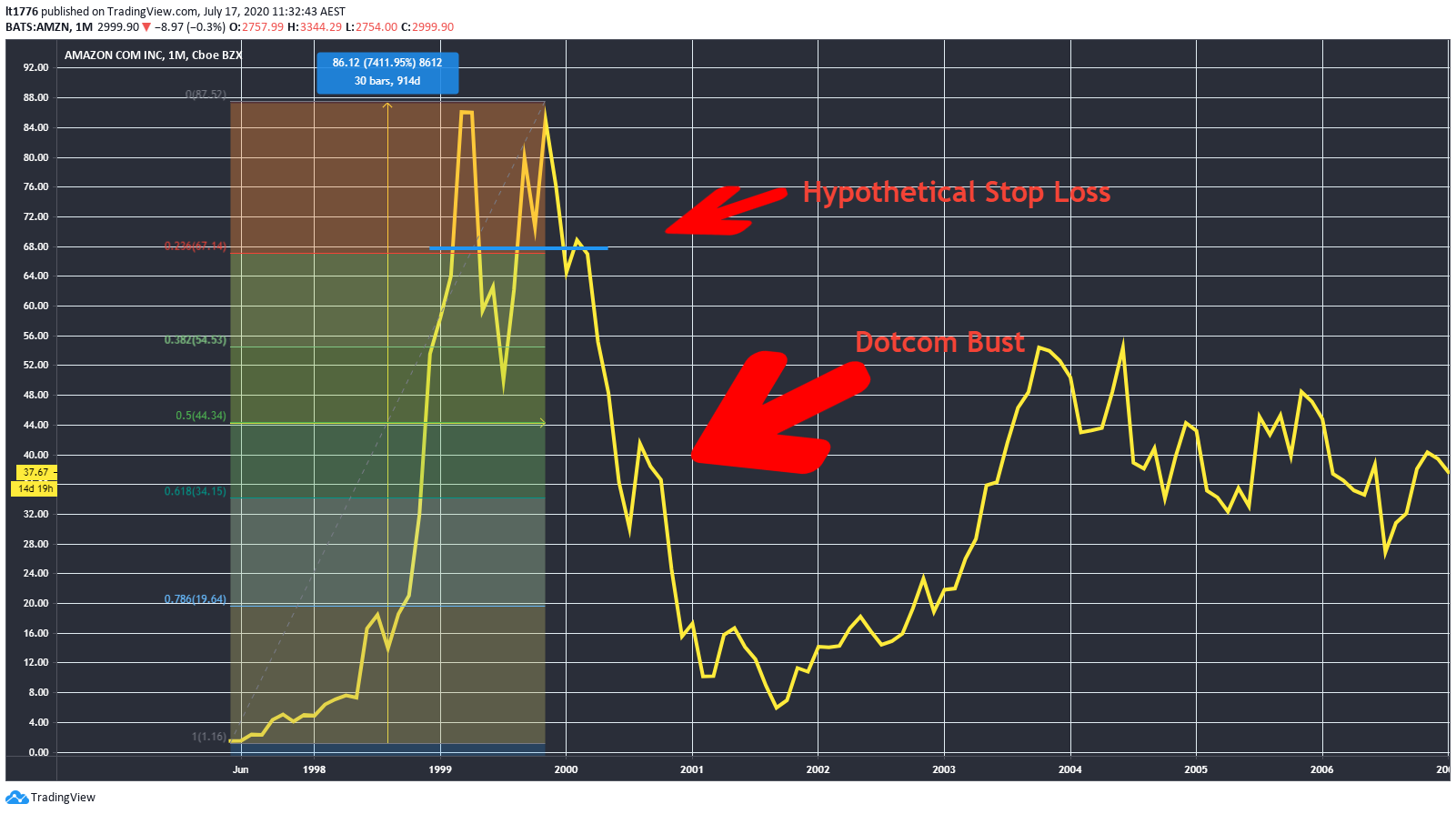

If you had bought Amazon at its IPO in May 1997, this is one hypothetical scenario (the chart is adjusted for stock splits):

|

|

| Source: tradingview.com |

You can see a more than 7,000% gain, which you could’ve been shaken out of with a 20% stop-loss or so put in at the peak.

When the dotcom bust unfolded, you would have looked like the smartest person in the room.

But of course, we all know what happened next.

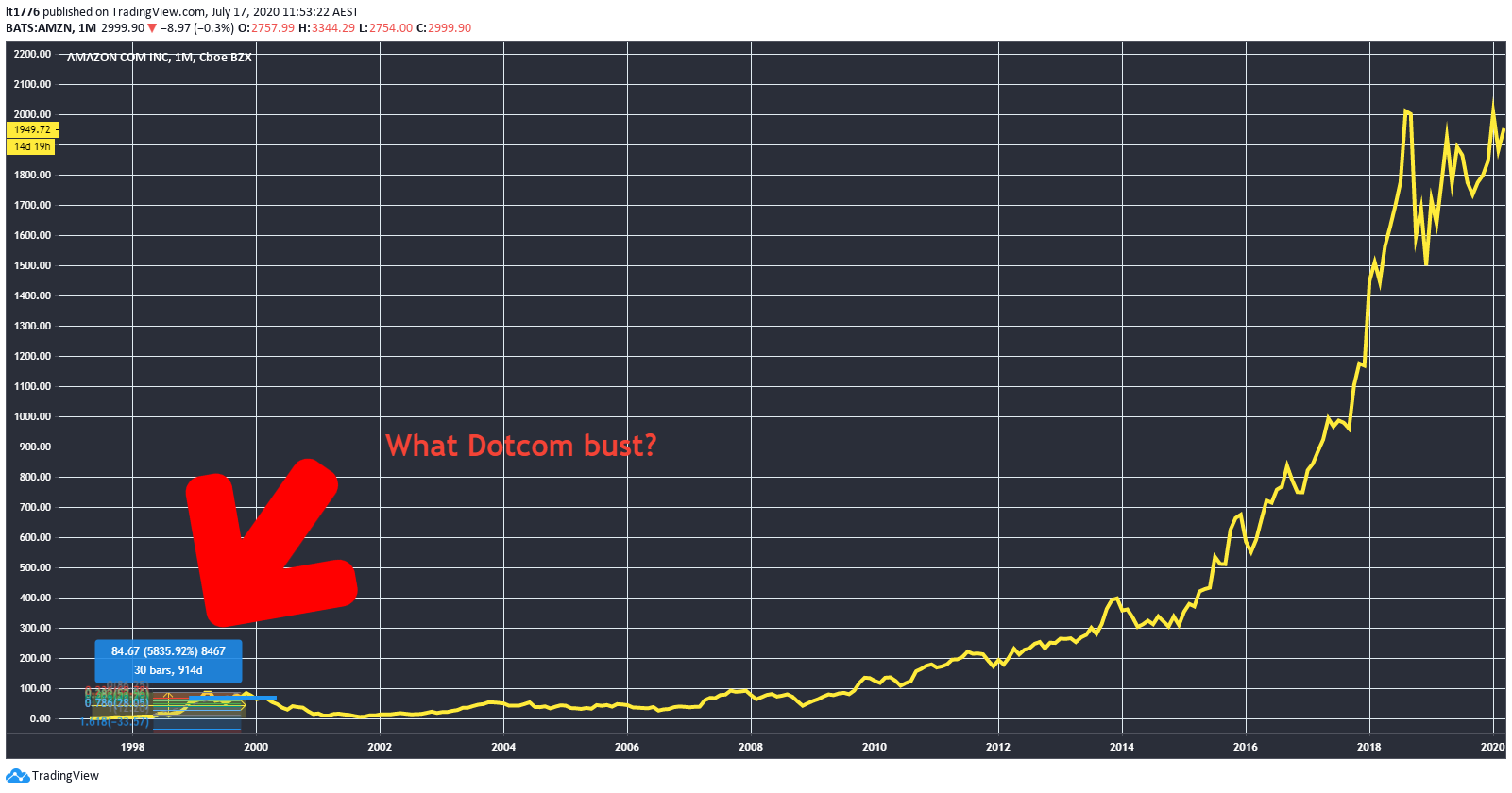

This is what this particular trade looks like in the context of the Amazon.com, Inc [NASDAQ:AMZN] share price chart through to today:

|

|

| Source: tradingview.com |

The dotcom bust was the tiniest blip.

Now let’s go back to the BNPL sector…

Stop-losses could be the way forward, half profits, and overall risk strategy

In an ideal world, if you hold BNPL shares the run will go on forever and everyone becomes very wealthy.

It may not work like this.

Even though they are not traditional lines of credit, you still need to pay them back.

To do that you need income via a job.

And job numbers are looking shaky globally.

So, you can imagine a scenario where even though it’s an interest-free payment plan, some people might struggle to pay companies like Afterpay back.

To guard against this, you could, for example, set a stop-loss and take half profits.

You bank a gain and hopefully watch the rest run knowing you can sleep better at night.

This is part of your overall risk strategy.

You also need to know what kind of company you are dealing with.

With a risky company like Amazon in its beginning stages, you might want to give it a lot of room to run.

An established dividend-paying company that is more mature, you may want to set a tighter stop-loss.

For example, take Commonwealth Bank of Australia [ASX:CBA] shares. CBA is a leader in Australia but is hardly going to take over the world. It may find efficiencies and grow market share in the Australian banking sector, but there is a much more defined cap on its expansion.

So BNPL may go on and take over the world, but you should be prepared to manage any pullback.

Know when to walk away

Glory hunting is not the best way to go about your portfolio.

Perhaps the best risk management fable here is Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler.

In it the protagonist, a gambling addict, discusses why he wants to play the roulette table:

‘No, it was not the money that I valued—what I wanted was to make all this mob…talk about me, recount my story, wonder at me, extol my doings, and worship my winnings.’

This is the perfect example of what not to do with your investments.

The stock market is not quite the same as a casino, but what do casino owners hate the most?

A gambler who walks away.

Regards,

|

Lachlann Tierney,

For Money Weekend

Lachlann is also the Junior Analyst at Exponential Stock Investor, a stock tipping newsletter that hunts for promising small-cap stocks. For information on how to subscribe and see what Lachy’s telling subscribers right now, please click here.

Comments