The year was 1980.

Gold hit a high of US$850 and The Vapors released ‘Turning Japanese’.

Gold and The Vapors were both at the top of their respective charts.

Few people remember the high in the gold price, but the chorus line of ‘Turning Japanese’ just stuck in your head…and still does.

‘I’m turning Japanese

‘I think I’m turning Japanese

‘I really think so’

Very few people actually knew (and probably still don’t know) what the lyrics are about.

According to The Vapors guitarist Robert Kemp:

‘[I]t’s a love song about somebody who had lost their girlfriend and was going slowly crazy, turning Japanese is just all the clichés of our angst…turning into something you never expected to.’

When it comes to matters of the heart, objectivity can go out the window.

Losing love can be devastating…

‘You’ve got me turning up and turning down and turning in and turning “round”’

Your world is suddenly thrown into chaos. How can you function without that certain someone in your life? Will life ever be the same again?

Little did The Vapors realise how relevant their 1980 hit would be to matters of finance in 2021.

The love of money can be just as powerful.

It’s said that ‘money is the root of all evil’.

This is blatantly untrue.

It’s our attitude towards money — the emotion we attach to it — that creates the forces of good and evil.

Money is not the root of all evil and all good…man is.

In 1980, the world had an affection for money, but was not in love with money.

The 1970s was a decade of high inflation, political upheaval, and social unrest.

In 1980, global share markets were down for the count and interest rates nudged 20%. Only the very brave or very foolish borrowed money at those rates.

Society’s attitude towards money was more respectful.

People paid off their homes. They still used lay-bys. Life insurance policies were the predominant long-term savings plan. And, for good measure, people put away a ‘few bob’ for a rainy day.

Households tended to save to do things…which is why every room in a 1970s home had its own unique style. Remember those loud wallpapers and swirly carpet combinations?

After inflation was tamed and brought permanently into the low single-figure range, our love affair with all things money began. Steady at first. But then the desire and intensity increased.

Shares. Investment properties. Derivatives. IPOs. SPACs. Meme stocks. Cryptos. Home equity loans. Credit cards. Pay-day lending.

Our love for money knew no bounds.

The political and corporate catchphrase is ‘growth, growth, and more growth’.

Everything had to expand — population, economy, house sizes, incomes, corporate earnings, government, entitlements, debts, asset prices.

The early years were refreshingly exciting times. Anything felt possible.

Millionaires became yesterday’s news.

Wealth was now being measured in the billions.

We were in love with this exciting world of abundant credit and asset price appreciation.

The old fuddy-duddys (our Depression-era parents) world of living within your means was replaced by this new and exciting temptress…seducing us into a world of instant gratification.

Oh, what a love affair we had with debt.

However, with too much of a good thing, there is always a recipe for disaster — too much cognac, too much chocolate, too many cigars — there is always a price to pay.

In 2008 our love affair waned. The financial world was bewildered.

‘You’ve got me turning up and turning down and turning in and

Turning ‘round’

Asset prices, like the emotions of one who is scorned, were depressed. The world was turned upside down in a matter of months.

The central bank matchmakers needed to rekindle the love affair. They needed the fairytale to continue…one with an eternal ‘happily ever after’ storyline.

Our central bank cupids provided the most romantic setting they could dream of — a candlelit dinner with an excessive serving of zero interest rates and QE.

The temptation was too good to resist.

In 2008 — just before the GFC — McKinsey Global Institute estimated total global debt was around US$142 trillion.

On 15 September 2021, Reuters reported…

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

Central banks turned our love for money into lust.

We covet money so badly, we’re prepared to take as much of it as we can from our future, in order to feed our need for immediate gratification.

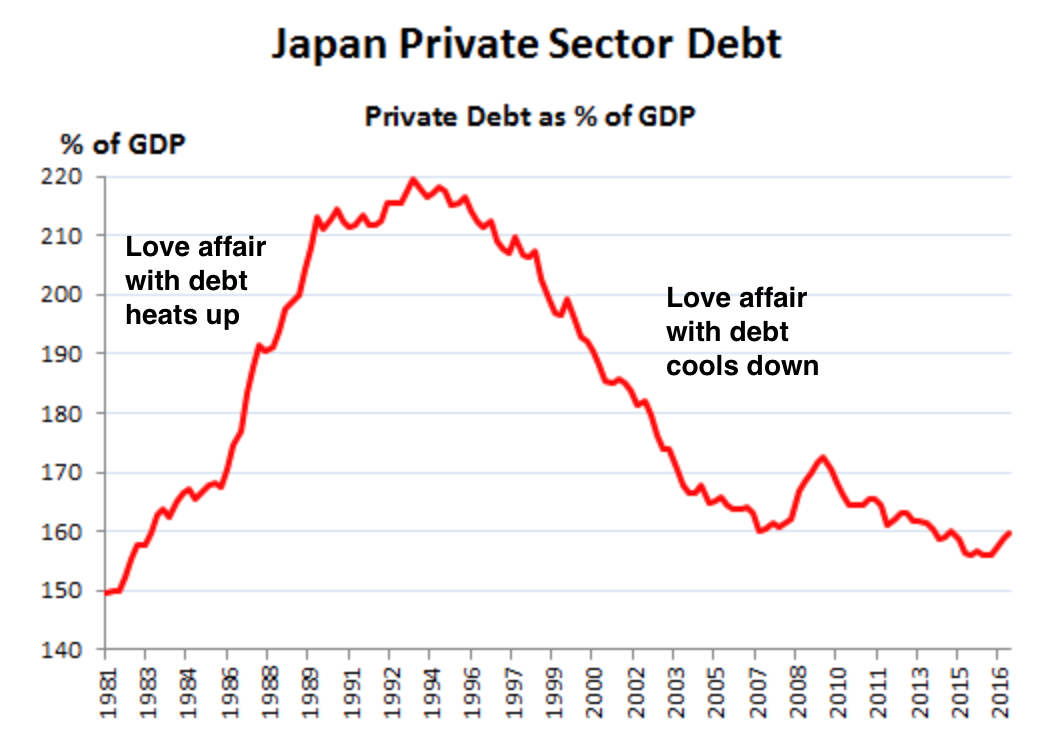

The 1980s was the decade when Japan’s lust for money made it the envy of the world.

The Land of the Rising Sun strode confidently on the world stage.

Japanese corporations aggressively expanded their business interests globally.

How did they do it?

The same way it’s always been done…borrow heavily from the future…

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

As private sector debt was building to its peak, so too was Japan’s share market:

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

Asset price inflation was not confined solely to the share market.

Japan’s property values were sent into another stratosphere…

‘At the peak of the [Japanese] bubble economy, Tokyo real estate could sell for as much as US$139,000 per square foot, which was nearly 350 times as much as equivalent space in Manhattan. By that reckoning, the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was worth as much as the entire US state of California.’

South China Morning Post

Debt fuelled economic growth.

Exponentially rising asset prices.

Overconfidence.

Is any of this sounding vaguely familiar?

Is Wall Street building to a market peak in late December to be followed by a collapse?

Could this trigger a relationship break-up between the private sector and debt?

If or more to the point, when, the Everything Bubble we are in does pop, it’s likely to be a game changer in the battle between inflation and deflation.

How to Survive Australia’s Biggest Recession in 90 Years. Download your free report and learn more.

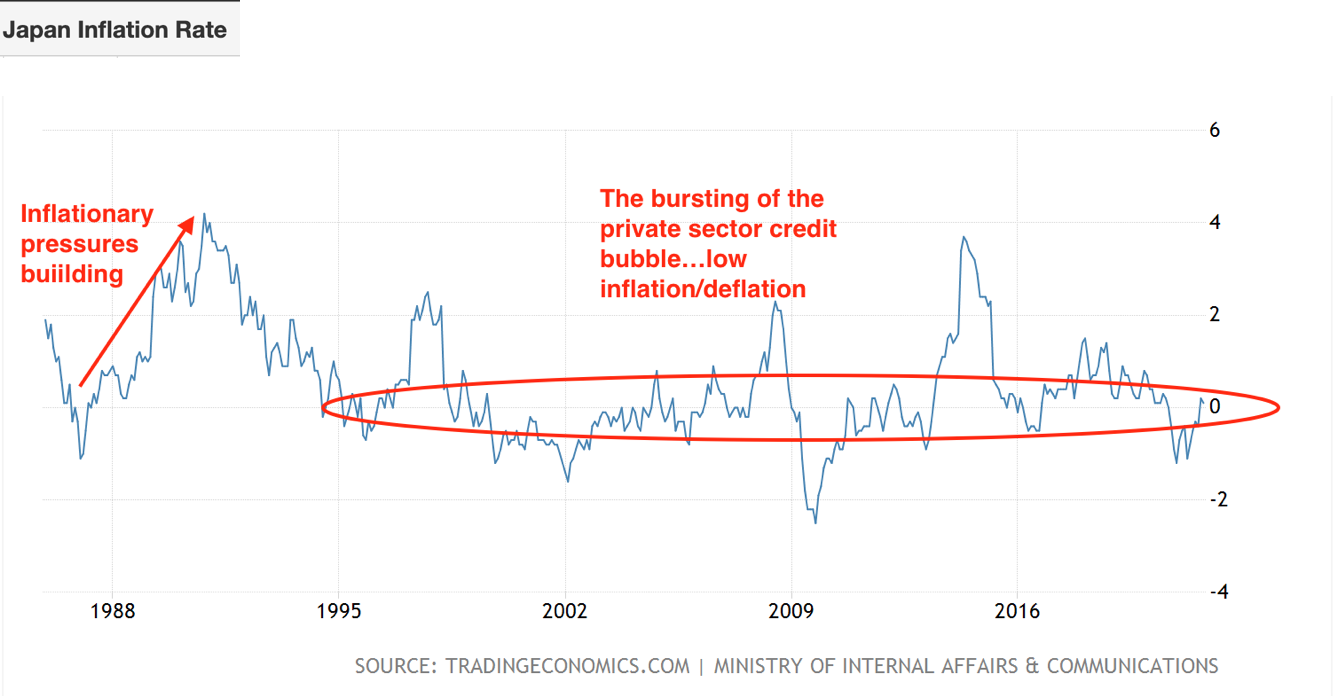

Prior to Japan’s bubble economy bursting, inflation pressures were building.

That’s only natural when you have a lot of borrowed money (demand) chasing a limited supply of goods and services.

After the air went out of the Private Sector debt bubble, concerns over inflation turned to worries about deflation.

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

Since Japan’s love affair with debt went cold in 1990, the Public Sector Cupid has fired off more arrows than a Braveheart battle scene.

The most notable being the three arrows of Abenomics.

Sadly, these all ended in the foot of former Prime Minister Abe.

In Japan, government efforts to encourage the private sector to embrace debt have largely failed.

The older generation (who were in their 40s and 50s in the 1980s) are now too old, AND the younger generations have seen how ugly it can get when the relationship breaks down…not too dissimilar to children who go through a bitter divorce and then, as adults have a reluctance to enter into marriage.

As with any relationship breakdown, there are differences on how you arrived at that point and the personalities involved.

Japan’s economic and demographic situation IS different from the rest of the West.

But what is not different, is that an economy hooked on the love drug of debt suffers when debt is spurned.

We caught a glimpse of this in 2008.

Prior to the GFC, inflation pressures were building in the US.

Then when the credit crisis hit, inflation plunged into negative territory…and remained in the low inflation zone.

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

And, here we are again, with inflation pressures building.

The vast majority have formed the view higher inflation is not transitory…it’s a more permanent fixture.

Don’t be so sure.

What’s not being factored in is a Japanese-style asset price collapse…and one is coming, of that I’m certain.

The pent-up demand we’re now experiencing (partly created by debt-funded purchases) could suddenly disappear.

The ending of our 40-year love affair with debt means there’s going to be a painful and difficult period of adjustment ahead.

I think we’re turning Japanese…I really think so.

Best wishes,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia

PS: Our publication The Daily Reckoning is a fantastic place to start your investment journey. We talk about the big trends driving the most innovative stocks on the ASX. Learn all about it here.