A central banker strolls along near a railway track.

His copy of The Economist in one hand, briefcase in the other.

It’s setting up to be another uneventful day until the central banker stumbles upon a distressing scene.

Five people are hogtied to the tracks! Incapacitated, they scream for help.

The banker is about to rush across to untie them when he hears a freight train approaching.

But that’s not all.

Another person is hogtied to a second track, which diverts from the track on which the five people are stuck.

The central banker neatly folds his copy of The Economist and places it in his briefcase.

He takes out a calculator, and to his horror, estimates that given the speed of the oncoming train and its shortening distance, he cannot save everyone.

He must choose.

Divert the freight train, and one hogtied person dies.

Or let the freight train continue on its course…killing the five hogtied victims.

What does he choose?

|

|

| Source: Imgflip |

The central bank’s monetary dilemma

Of course, the central banker might not even care and leave the scene unfazed, mumbling, ‘Not my problem’.

After all, that’s a common stereotype, humorously illustrated by the following joke.

A man needs a heart transplant. The doctor tells him: ‘I can give you the heart of a five-year old boy.’

‘Too young’, replies the patient.

‘How about that of a 40-year-old investment banker?’

‘They don’t have a heart.’

‘A 75-year-old central banker?’

‘I’ll take it!’

‘But why?’

‘It’s never been used!’

Yet, what if the central banker did ponder the moral dilemma seriously? What would his reasoning be?

Which brings me to the heart of today’s piece.

The choice confronting the strolling central banker is a famous moral dilemma studied by philosophers.

But do central banks have their own version of the dilemma in the form of a choice between high inflation and recession?

What’s worse, inflationary or recessionary times?

When confronted with letting inflation run high versus triggering a recession, what do the central bankers prefer?

Everyone seems to think a recession is coming

Last week I mentioned the voluminous talk about recession in the press lately (to which I am adding).

How many headlines have you seen this month about this or that bank or this or that economist forecasting a recession?

I probably see at least one a day.

The heavy coverage given to recession indicates a consensus is forming about its growing inevitability.

According to nearly 70% of leading academic economists polled by the Financial Times earlier this month, the US economy will tip into a recession next year.

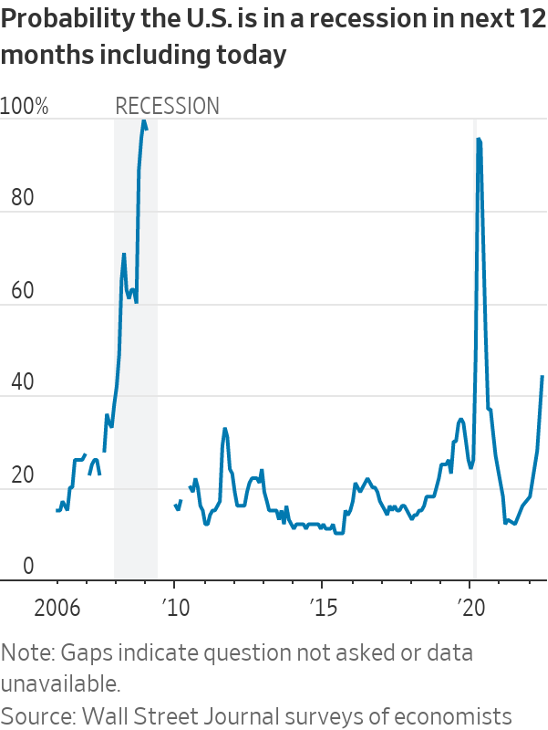

A similar story came from The Wall Street Journal, which reported this month:

‘Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal have dramatically raised the probability of recession, now putting it at 44% in the next 12 months, a level usually seen only on the brink of or during actual recessions.’

|

|

| Source: Wall Street Journal |

And countless investment banks have come out predicting a similar economic downturn in recent weeks.

Even the New York Fed released a report placing the probability of recession above 50%:

‘According to how the New York Fed models the economy’s path, the report said that “the chances of a hard landing…as occurred during the 1990 recession are about 80%,” while the probability of a “soft landing,” in which gross domestic product essentially remains positive over the next 10 quarters, is 10%.’

So, economists and market analysts are putting the probability of a recession at a level usually only seen when the economy is on the brink an actual recession.

That poses a question.

If you can predict a recession, can you prevent it?

If there is such strong consensus that a recession is likely, can central banks do anything about it?

In other words, if you predict a recession, can you prevent it?

This very question was pondered a few years ago by economist Scott Sumner in his influential The Money Illusion.

Here is an excerpt (emphasis added):

‘We should not ask economists to predict recessions—we should ask them to prevent recessions. If we could predict them, then we could prevent them. Here’s James Hamilton, a noted business cycle expert: “You could argue that if the Fed is doing its job properly, any recession should have been impossible to predict ahead of time.” Strictly speaking, Hamilton’s observation applies only to recessions caused by demand shocks, but in practice supply shocks are also pretty unpredictable.

Most recessions occur precisely because policy makers are unable to predict them.‘Indeed, to say that economists are not good at predicting recessions is an understatement. Economists are extraordinarily bad at predicting recessions. The past three recessions were not predicted by a consensus of economists until the recession had been under way for many months.

‘That’s right, not only can economists not predict the future; they cannot even predict the present—they often can’t even predict the recent past. In July 2008, economists were not able to “predict” that the economy had been in recession in January 2008!’

Of course, you could push back here.

What if you can’t prevent recessions even if you can predict them? For instance, a meteorologist who predicts thunder tomorrow can’t prevent it.

But economies, unlike weather events, are reflexive. Economies contain adaptive people and central banks possess the tools to spur our adaptive qualities.

A looming recession is not an inevitable weather event.

Which brought Sumner to a very interesting conclusion:

‘I am going to argue that the only recessions that we ought to be able to forecast are those that we want to occur.’

If it’s the case that central banks will prevent recessions they can predict, then we’re left with two scenarios, in my view.

The Fed can’t and/or isn’t predicting a recession in 2023.

Or the Fed is predicting a recession…and is choosing it over inflation in a central bank version of the trolley dilemma.

The first scenario is hard to accept considering how inundated we are with news that leading economists and top investment banks are forecasting a recession in 2023.

Which leaves us with the second scenario: a recession we ought to be able to forecast and one we want to occur.

As Bloomberg reported earlier this month (emphasis added):

‘“The chairman of the Fed doesn’t want to let the ‘r’ word slip out of his mouth in a positive way, that we need a recession,” former US central bank policy maker Alan Blinder said. “But there are a lot of euphemisms and he’ll use them.”

‘“I’ve become more pessimistic about the opportunity of stabilizing inflation at an acceptable level without a recession,” said JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief economist Bruce Kasman. He sees a dynamic developing in which a protracted period of high inflation and a tight labor market leads to elevated wage demands and more costs for companies.’

The second scenario sounds outré, but not if central banks think a recession is the only way to realistically curb inflation levels countries have not seen in decades.

Regards,

Kiryll Prakapenka,

For Money Morning

PS: After heavy selling in recent weeks, ASX lithium stocks have rebounded somewhat this week. While plenty of lithium names were bid up to elevated levels, the underlying story is still strong. EVs are the future and the world will need more battery materials to electrify our vehicles.

But, clearly, some of the speccier lithium stocks have been overbought. The lithium euphoria of last year exhausted any easy gains left to make in the sector.

But the overarching narrative backing lithium and battery stocks is still sound. The key now is finding investment opportunities on the edge of the market’s awareness.

Last week, my colleague and Australian Small-Cap Investigator editor Callum Newman put together a report on his three favourite battery plays. Callum has found three stocks he thinks are much less obvious but no less compelling if you’re prepared to look ahead one or two years.

Callum thinks one of the battery stocks in his new report could be one of the most exciting nickel projects in the world.

I highly recommend you to check out Callum’s report here.