Dear Reader,

Earnings season is nearly over but everyone is talking about inflation.

The latest monthly CPI reading came in lower than expected, and the market reacted well. But is this warranted? And what’s the bond market telling us?

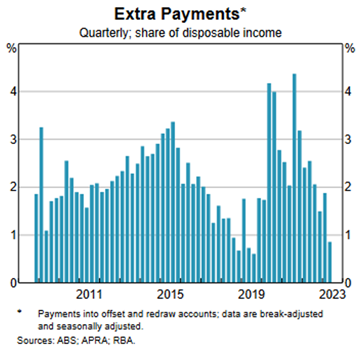

Inflation is cooling, because households are retrenching. The US consumer is running down their savings and the amount Aussie households are putting into offset accounts is at multi-year lows.

As Greg Canavan and I discuss, it’s a trend that will continue. The cause behind disinflation is restrictive monetary policy straining the consumer.

Is that really a good outlook for stocks?

Speaking of stocks, we look at two big Aussie businesses — Harvey Norman [ASX:HVN] and Brambles [ASX:BSB]. Are both overvalued?

Finally, we turn to the energy transition and its costs.

Greg explains the importance of the energy return on investment and why the metric is vital for civilisation.

A low energy return on investment is a low standard of living.

Which way are we headed?

Central banks’ battle against inflation

Australia’s latest monthly CPI indicator rose lower than expected, to 4.9% in the 12 months to July, down from 5.4% in June.

Good news!

The biggest contributors to the increase were housing (7.3%) and food & non-alcoholic bevvies (5.6%).

Counterbalancing these spikes were price falls for automotive fuel (down 7.6%) and fruit & veggies (down 5.4%).

But, some bad news.

Core inflation — excluding volatile items — was down less, from 6.1% to 5.8%.

And we had a big jump in electricity prices, too, despite the recent rebates.

Electricity prices rose 15.7% in the 12 months to July and a whole 6% in the month of July alone.

The spike follows price reviews across all capital cities.

Rebates introduced last month mitigated the price rises for some households, with the Energy Bill Relief Fund providing eligible households deductions ranging from $40 to $250.

But the ABS has smart data crunchers who figured out that, excluding the rebates, electricity prices would have recorded a monthly increase of 19.2% in July!

Inflation is cooling, but we are far from hitting the Reserve Bank’s target of 2%.

The US Open is on so allow me a tennis analogy.

In the battle with inflation, are central banks up a break in the fifth set?

They have the upper hand and the end is seemingly in sight. But they are yet to serve it out, and inflation can still stage a comeback.

Greg agrees central banks are leading the match, but he doesn’t think we’re in the final set. More like the third or fourth.

The endgame isn’t yet upon us. Interest rates are staying higher for longer to rid the system of any latent inflationary tendencies.

That will mean more pain for households.

Discretionary spending is falling and we are putting less into offset and redraw accounts.

Just look at the chart below.

Source: RBA

When money gets tighter and mortgage costs rise, you’re less magnanimous with those extra payments.

Harvey Norman and Brambles: are both overvalued?

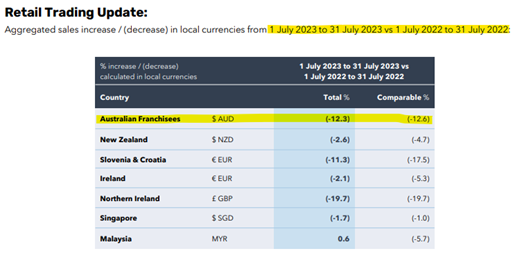

On the theme of falling discretionary spending, Harvey Norman released its FY23 results this week.

A telling admission was its sales update for the month of July.

July comparable sales for its key Australian franchisees were down 12.3% on the same month last year.

No country registered comparable sales growth in the period.

Source: Harvey Norman

As always, the question is how much of this has the market already priced in? And where does Harvey Norman go from here?

Back to the mean, I think.

Harvey Norman’s average FY23 equity was around $4.38 billion. On a net income of $546.8 million, that’s a ROE of 12.5%.

What was the ROE during Harvey Norman’s favourite comparison year, FY19?

13%.

Profitability seems to be normalising.

What about the valuation?

Using a discount rate of 8% and FY24 consensus estimates, we get a valuation of $4.20 a share, slightly above Thursday’s closing price of $4.04 a share.

It seems the giant retailer is fairly priced.

Which means the market’s implied forward assumptions are roughly as follows:

- FY24 ROE of 9%

- Payout ratio of 73%

- Discount rate of 8%

As for Brambles, the business posted solid profit and revenue growth in FY23 despite admitting 2H23 saw ‘progressive destocking across manufacturer and retailer supply chains’.

Its strong FY23 return on capital invested of 18.5% suggests presence of market power.

But is the market bidding Brambles up too much? Is the ‘certainty premium’ at play again here?

Energy return on investment and the fate of economies

We’ve talked about Return on Equity.

But there’s a metric more profound than that.

Energy Return on Investment (EROI).

Energy drives economic growth.

In fact, Vaclav Smil wrote that to ‘talk about energy and the economy is a tautology: every economic activity is fundamentally nothing but a conversion of one type of energy to another’.

And the more efficient this energy conversion, the better.

That’s what the EROI metric seeks to measure.

EROI is basically a ratio of useful energy received from some extraction process to energy expended extracting it.

A ratio of one means that you’re using (say) 100 units of energy to extract 100 units of energy. Why bother?

As one paper on EROI put it:

‘In fact, heat engines can be seen as economic amplifiers, with the EROI, or R for short, as the amplification factor. Man provides 1 unit of usable work — and technology amplifies it R-fold by delivering R units. Using a more vivid metaphor, the EROI tells us how much work machines can do for us. Thus, the historical change of R of society’s power generation is the most important proxy for industrial progress and wealth evolution, hovering around 1 for most of human history, until industrialization — the large-scale application of heat engines — began boosting it upwards starting in the late 18th century, reaching values of multiples of 10 for OECD-like societies of today.’

The higher the EROI, the higher a society’s standard of living.

It cannot be otherwise.

As Mark Buchanan wrote in Nature Physics journal:

‘After all, the energy used up in extracting energy doesn’t create any real economic output, but merely goes to providing the energy that can then be used to produce economic output. Hence, if other factors remain fixed, a temporary drop in EROI, for any reason, means we need to use up more energy in producing energy, and therefore have less to spend on real economic activity — on this logic, economic growth should then falter

‘Indeed, this seems to be the case empirically. Over the past 150 years, periods of low EROI — implying a temporary decrease in energy available for useful economic activity — have been correlated with lower rates of economic growth.’

And this brings us to the crux of this week’s episode.

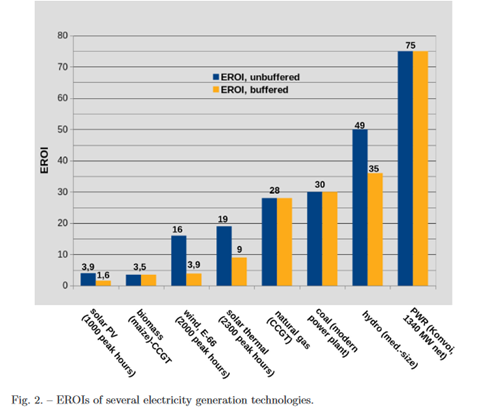

The energy transition may incur costs we have not bargained for.

Many of the energy sources we are shifting to have lower EROI than the fossil fuels we are leaving behind.

Source: Weissbach et al., 2018

And nuclear energy, with an unmatched EROI, is being mothballed here and in many other countries.

So, what does this all mean?

For energy prices, standards of living, markets, and even societies in general?

Watch the full episode to find out (I know, sorry!).

Enjoy the episode!

Regards,

Kiryll Prakapenka, for Money Morning