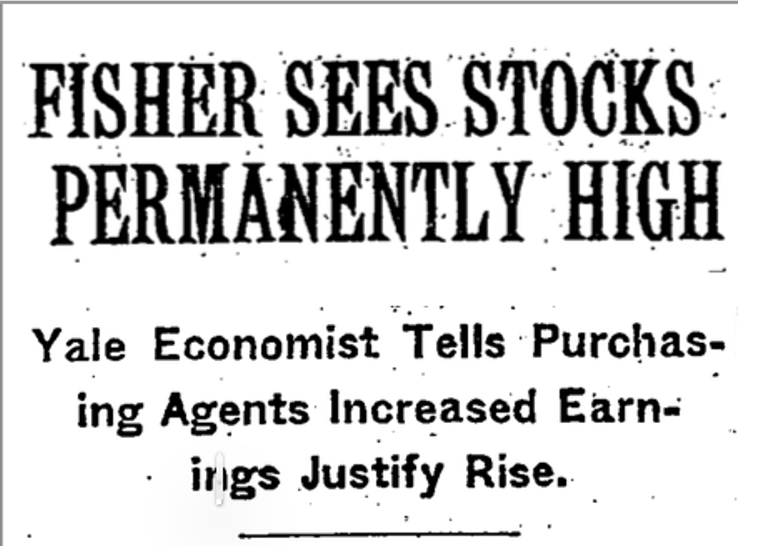

What if, in September 1929, you are a highly regarded Yale University economist who believes ‘shares have reached a permanently high plateau’?

From the 3 September 1929 edition of The New York Times:

|

|

| Source: NYT |

What if your conviction is so absolute, you invest everything you own in the market?

History provides the answer to the ‘what if’ questions (emphasis added):

‘Irving Fisher, one of the leading economists in the U.S. at the time, was heavily invested in stocks and was bullish before and after the October sell offs; he lost his entire wealth (including his house) before stocks started to recover.’

Economic History Association

What if Irving Fisher had held a different belief?

What if he’d determined investment markets operate in cycles…rotating from high to low and back again?

Life would’ve been vastly different for him.

What if questions open your mind to possibilities

In July 2005, Ben Bernanke (former US Federal Reserve Chairman) was asked in a CNBC interview (emphasis added):

‘What is the worst-case scenario if in fact we were to see [housing] prices come down substantially across the country?’

Bernanke’s reply was (emphasis added):

‘Well, I guess I don’t buy your premise. It’s a pretty unlikely possibility. We’ve never had a decline in house prices on a nationwide basis. So, what I think what is more likely is that house prices will slow, maybe stabilize, might slow consumption spending a bit. I don’t think it’s gonna drive the economy too far from its full employment path, though.’

Bernanke deemed the possibility of the ‘what if’ scenario to be…unlikely.

With hindsight, we know Bernanke was wrong, wrong, and wrong.

Irving Fisher and Ben Bernanke made the mistake of taking ‘what has been’ as a permanent condition…what has been good will continue to be good…or, even better.

Hyman Minsky’s hypothesis — ‘stability creates instability’ — could have saved them both a great deal of embarrassment.

The psychological process goes something like this…

The longer the period of price stability, the greater the likelihood we think this pattern will continue.

Safe in the belief share/property/crypto values never go down, investors discount risk out of the investment equation.

With a guaranteed road to riches — because prices only ever go up or at worse, stabilise — the thinking becomes ‘why wouldn’t you borrow as much as you can to participate in the rapidly appreciating asset class’?

A prolonged period of price increases lulls people into a false sense of security.

Flashing dollar signs blind them to the risks in their financial overreach.

Based on the physics of ‘for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction’, history shows us ‘the longer the period of stability, the greater the eventual instability’.

When you preface a question with ‘what if’, you open your mind to possibilities and alternatives.

Some ‘what if’ questions to ponder

Over the past few years there’ve been several ‘what if’ questions I’ve been grappling with.

What if the past 60 years of economic growth and financial prosperity wasn’t normal?

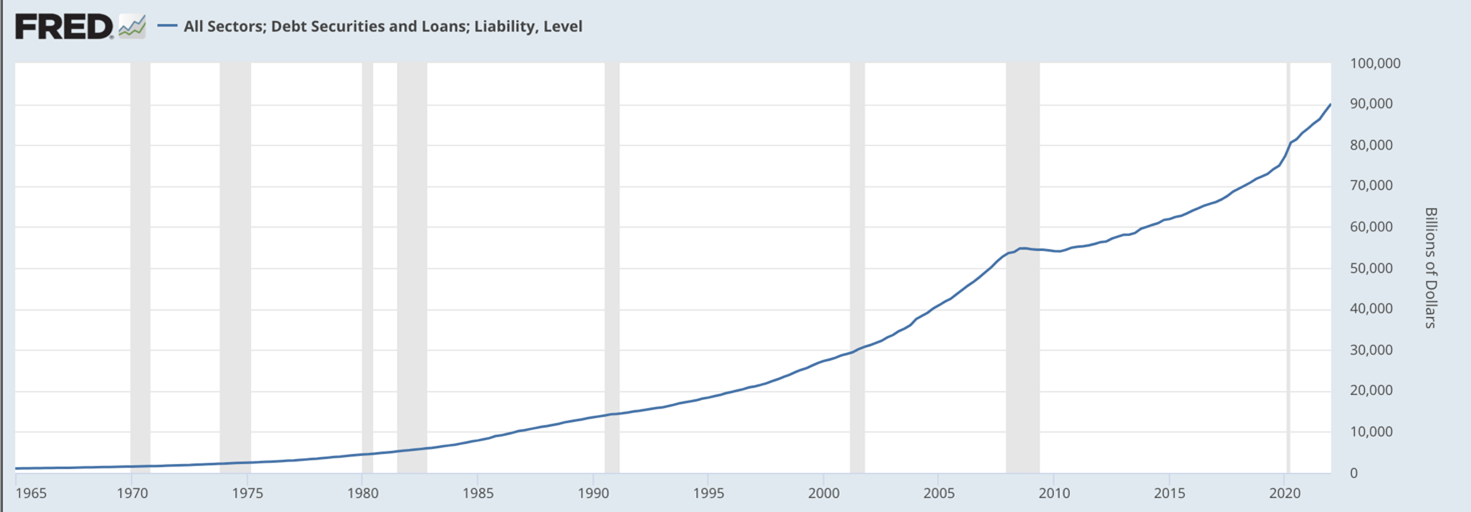

Since the mid-1960s, US debt (public and private) has increased from US$1 trillion to US$90 trillion:

|

|

| Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data |

This chart is a classic representation of the boiling frog theory put into practice.

Year after year, a little more debt was added. People became used to the higher debt loads.

Reduce rates a little and they could dial up debt levels a little more.

It’s this slow and almost unnoticed layering of debt levels that creates the mindset of ‘normality’. Year after year, decade after decade, debt levels accumulate.

The concept of constant growth (albeit interrupted by the occasional recession) is not only taken for granted but is expected.

Growth, growth, and more growth is the mantra.

But what if the ‘growth’ of the past 60 years has largely been a function of expanding debt levels in the global economy?

We’ve made tremendous advances over the past six decades — technology and healthcare immediately come to mind.

However, to avail ourselves of these advancements and improve our lifestyles, it’s required us, as a society, to go deeper and deeper into debt.

Accessing these ‘mod cons’ and ‘medical marvels’ with more savings and less debt would’ve delivered a much slower pace of growth.

Accelerated growth, fuelled by high octane debt, created our ‘normal’ view of economic development.

This artificially created growth is evident in the performance of the Australian share market pre- and post-1980.

From 1875–1980 (105 years), our market averaged a compound growth rate of 4.5% per annum.

Since 1980, the All Ords annual compound rate accelerated to 6.6% per annum.

Is it just a coincidence that the share market’s increased growth rate has occurred precisely at the same time the world went deeper into debt?

Or did decades of debt-fuelled economic growth propel the share (and property) market/s to growth rates well above their historic averages?

Personally, I think it’s the latter.

What if debt levels keep rising to maintain past growth levels?

It’s possible. But to quote Bernanke…unlikely.

Trees DO NOT grow to the sky and, as history shows, neither does debt.

The higher the debt pile increases, the greater the instability in the structure.

Compounding debt levels is not an infinite exercise.

If it was, the term ‘debt crises’ wouldn’t exist.

If you recognise that debt accumulation (which these days is being used in greater quantities for unproductive purposes) has a use-by-date, then the next what if question is:

What if in the coming years and decades, debt levels fall (not even collapse)?

Inflation (the air in the credit bubble) could be replaced by deflation (the air escaping the credit bubble). I know in the current environment this sounds absurd. But so too did the prospect of the Great Depression in 1928 and the thought of a nationwide US property collapse in 2005.

The advent of deflation heralds in growth rates much lower than ‘normal’…what we’ve been conditioned to expect from the past six decades.

Growth assumptions (based on what has been, will continue to be) on population, household formation, property values, wages, welfare, share prices etc., will all be thrown into disarray.

In this what if scenario, using past data as a reliable guide to future outcomes would be sheer folly.

Government budgets — based on rosy growth projections — would go deep into the red.

On an individual level, retirement income projections based on 6%-plus per annum compound return, would fall well short of the mark.

Property investors relying on an assumed level of capital growth (to offset income losses incurred from negatively geared property) is likely to scuttle many a well laid plan.

Plans made with all good intentions, but based on incorrect assumptions, are bad plans.

Garbage In, Garbage Out…GIGO.

Making growth assumptions based on an extended period of unprecedented debt growth is, in my opinion, a mistake…permanently high plateaus DO NOT exist.

The road travelled is unlikely to be the one we’re going to travel in the coming years and decades.

The ‘stability’ of the past 60 years has culminated in a mindset of excessive risk-taking.

It’s this collective thinking that’s made our economic and financial system highly unstable and extremely fragile.

What if I’m wrong?

Then adopting a cautious approach to your assumptions means you’ll be in for a pleasant surprise…a case of ‘underpromise and overdeliver’.

What if I’m right?

You’ll be so glad you adopted a more conservative approach to the allocation of your capital, reduction of debt, and living within your means.

Institutional economists (drawing on past performance data) all suggest mostly positive economic conditions ahead. Are they right? Or are they falling into the same trap as Fisher and Bernanke?

History clearly shows that good and bad times DO NOT last forever.

Excesses need to be corrected.

The Great Depression was 92 years ago — the further we go away from the last one, the closer we are to the next one.

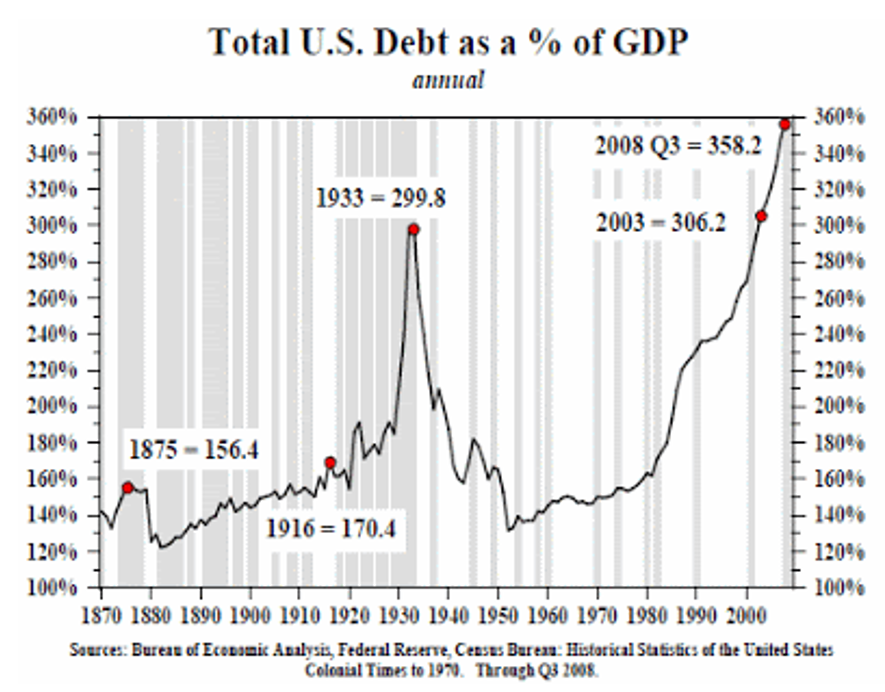

What was the cause of the Great Depression?

A debt build-up that began in 1880 and ended in the 1930s…it took around six decades for stability to create instability.

|

|

| Source: Capital Ideas |

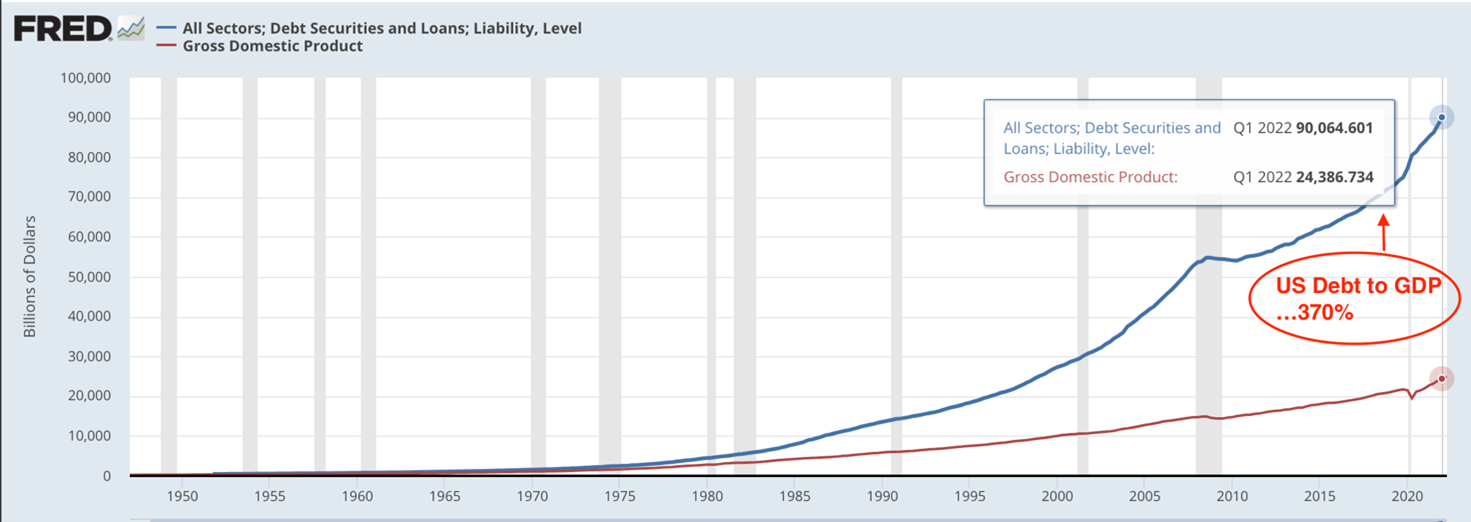

The latest US debt-to-GDP reading is 370%…well above the levels reached in the early 1930s:

|

|

| Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data |

What happened after the Great Depression was unlike anything anybody had experienced in their lifetimes.

At the height of the Roaring Twenties, hardly anyone would have considered ‘What if this is too good to be true? What if this all ends?’.

Failure to consider the ‘what if’ scenarios left society ill-prepared for an abrupt reversal of fortunes.

The question thinking investors of today need to seriously consider is…

What if this happens again?

Are you financially and emotionally prepared for tougher economic times?

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia