The explanation for this bail-in/bailout distinction takes us back in the time machine to the period from 2008–14.

SVB is more than a wipeout for stockholders. SVB is the first example of a financial regulatory rule put in place by the G20 in November 2014 in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. There was a popular outcry against using taxpayer money in 2008 to bail out bank CEOs who were making millions, and whose banks are still around. In response, the G20 agreed that in future financial crises, there would be no more bailouts with taxpayer money. The new approach was to be a bail-in.

This means that in the case of a failed bank, equity would be wiped out first, and then depositor funds would be converted to contingent claims if they were above the insured amount. Bank deposit insurance is US$250,000 per deposit in the US and €100,000 per account in the EU.

More than 95% of the deposits in SVB exceeded the insured amount. This means those deposits were gone, according to the FDIC’s press release on 10 March 2023. Depositors were to get a ‘receivership certificate’ from the FDIC, which may or not have been worth anything depending on what the FDIC might collect from asset sales.

It could take months to ascertain the size of the SVB losses and a year or longer to sell assets. Depositors might ultimately get 90 cents on the dollar or 10 cents on the dollar. No one would know until the FDIC computed the size of the hole in the SVB balance sheet. The losses would get worse as the fire sale proceeded and asset values dropped further.

Contagion and systemic risk

The systemic problem is that those lost SVB deposits represent venture capital investments and working capital balances for thousands of tech startups and early-stage tech companies. They would have no cash to spare. This means they would not be able to make payroll, pay the rent, pay vendors, or conduct business. Those tech firms would likely fail, tens of thousands would lose jobs, and the ripple effects would spread from there.

The issue of contagion from SVB is interesting and not well understood. Everyone is worried about other banks failing. That’s a real possibility and is likely to happen. But that’s far from the only kind of contagion.

Silicon Valley companies and tech firms around the world held in portfolio by SVB would see their stock prices decline as the FDIC conducted a fire sale of assets to pay creditors. Buyers would lower their bids knowing the FDIC was desperate to raise cash.

There’s an unhealthy tension between how quickly you dump assets and how much you can get for them. Generally, a slower approach gets higher prices, but that slow approach may strangle the startups. Top Venture Capitalist (VC) firms warned startups that if their money was lost in SVB, they would not be getting new funding from the VCs. So they would fail.

The bail-in became a bailout

The FDIC announcement of a bail-in of depositors held sway for about 48 hours. Around 6:00pm ET on 12 March, a joint announcement by the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and US Treasury said, in effect, ‘just kidding’. The bail-in was abandoned.

Instead, the regulators announced that 100% of depositors at SVB would be protected in full. The bailout was back. The 2014 bail-in rules, which had been in place for nine years, were thrown under the bus in two days. (In passing, the press release also announced that another large bank, Signature Bank, was being shut down by the FDIC. Their depositors were protected in full also).

This was clearly a bailout of Silicon Valley, but it’s bigger than that. The depositors at SVB, tech startups, and mature companies were bailed out when the Fed/FDIC abandoned the US$250,000 deposit insurance limit. But those companies had investors of their own (large VCs and high-net-worth individuals), and they were also bailed out by not having to take losses on those investments.

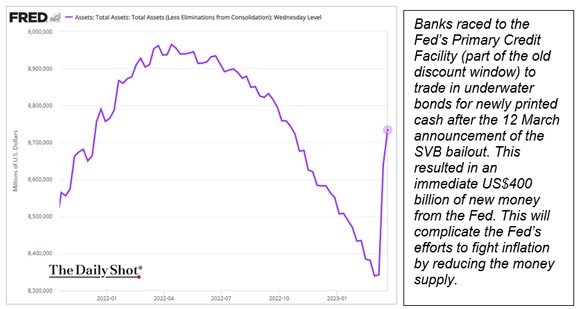

Not only that but the entire banking system was bailed out by the 12 March announcement. This is because the Fed invited any member bank to deliver underwater Treasury and mortgage securities and get 100% cash (no haircut) for the full par value of the bonds — even though many are deeply underwater on a mark-to-market basis.

The Fed, FDIC, and Treasury credibility on the subject of ‘no bailouts’ is now in shreds. This is a bailout of monumental proportions, which mainly benefits tech entrepreneurs, wealthy investors, and banks.

|

|

| Source: FRED |

Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, said this bailout would not involve taxpayer money. This is false for two reasons: US$25 billion of the bailout money is from the Exchange Stabilisation Fund (ESF), which was created in 1934 after FDR confiscated gold from everyday Americans at US$20/oz and repriced it at US$35/oz. That’s a 75% mark-up profit for the government that was taken from Americans’ pockets at the time. The ESF has been growing ever since, and the Treasury can use the money without Congressional authorisation (Robert Rubin used it in 1994 to bail out Mexico when Congress refused).

More to the point, the rest of the money comes from the FDIC insurance fund. This will be badly depleted by the SVB and Signature bailouts. It will be replenished by increased FDIC insurance premiums on banks. The banks will pass the insurance costs along to consumers in the former of lower interest or higher fees.

So, in the end, the everyday US taxpayer always pays. The cost is simply disguised through the FDIC. The winners are billionaires like Bill Ackman, Mark Cuban, and others.

Regards,

|

Jim Rickards,

Strategist, The Daily Reckoning Australia