Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are coming. Here’s why that may worry you.

Dear Reader,

As veteran investment strategist Jim Rickards pointed out yesterday, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are much closer to becoming a reality than many realise.

What was once the reserve of arcane financial speculation could soon become embedded in our daily lives.

The digital yuan — or the e-CNY — is already live.

Earlier this year, the e-CNY was being used to make more than two million yuan of payments daily at the Beijing Winter Olympics.

But while China is the biggest exponent of the CBDC, it’s not the only one.

As Jim summed up in his piece:

‘Nine other countries have already launched CBDCs. Europe is not far behind and is testing the digital euro under the auspices of the European Central Bank.

‘The US was lagging, but is catching up fast, according to this article.

‘The Federal Reserve was studying a possible Fed CBDC at a research facility at MIT. Now the idea has moved from the research stage to preliminary development. Fed Chair Jay Powell said, “A US CBDC could…potentially help maintain the dollar’s international standing.”’

And just last month, our own Reserve Bank of Australia updated anyone who cared to listen that it’s ‘actively researching central bank digital currency as a complement to existing forms of money’.

CBDCs are no faraway gimmick. We must come to terms with the possible implications of its potential adoption.

And the implications of widespread CBDC use may worry you.

Here are three reasons why:

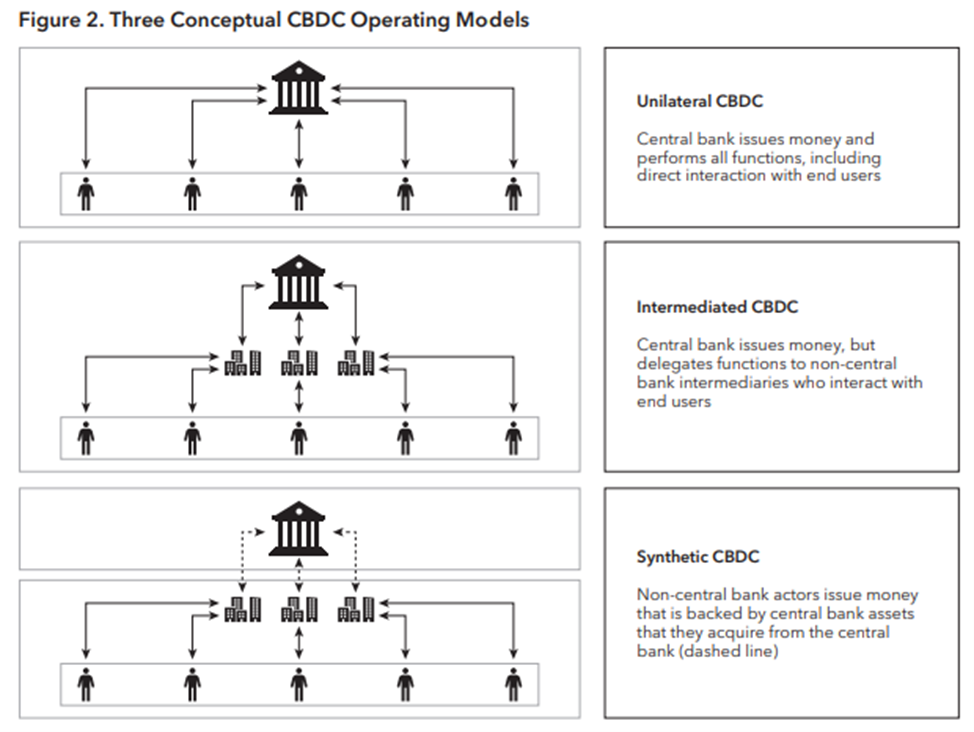

Source: IMF

CBDCs, privacy, and surveillance

The number one concern for adopting CBDCs is privacy.

The widespread use of a CBDC could make financial surveillance much easier.

Take the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The BIS dubs itself the bank for central banks.

Well, in its view, CBDCs are a great development.

But it acknowledges that identification is ‘central in the design of CBDCs’.

The BIS goes on:

‘A token-based CBDC which comes with full anonymity could facilitate illegal activity, and is therefore unlikely to serve the public interest.

‘Identification at some level is hence central in the design of CBDCs. This calls for a CBDC that is account-based and ultimately tied to a digital identity, but with safeguards on data privacy as additional features.

‘A digital identity scheme, which could combine information from a variety of sources to circumvent the need for paper-based documentation, will thus play an important role in such an account-based design. By drawing on information from national registries and from other public and private sources, such as education certificates, tax and benefits records, property registries etc, a digital ID serves to establish individual identities online. It opens up access to a range of digital services, for example when opening a transaction account or online shopping, and protects against fraud and identity theft.’

[openx slug=postx]

For BIS, a CBDC with full anonymity doesn’t serve the public interest because it could facilitate illegal activity.

But a CBDC backed by a full-scale ‘digital identity scheme’ that draws on a swathe of private information doesn’t sound so bad at all.

What could go wrong, right?

There are some who realise the dangers.

The Harvard Business Review quoted the discomfort felt by some US politicians regarding CBDCs:

‘“Central banks increase control over money issuance and gain insight into how people spend their money but deprive users of their privacy,” notes Congressman Tom Emmer (R-MN), adding, “CBDCs would only be beneficial if they are open, permissionless and private.”’

Even the International Monetary Fund grasps the thorny issue of privacy and the threat CBDCs pose to it:

‘Anonymity is one of the key traits of cash, and the rise of digital payments threatens the lawful or legitimate preference for anonymity by certain segments of the public or for certain purposes—such as buying a present for one’s spouse. Anonymity is also connected to financial inclusion: non-anonymous payment services often require forms of identifications that can be difficult or costly to obtain.’

The battle to protect one’s privacy will likely be one of the focal points in debates over adopting CBDCs.

CBDCs, stifling innovation and crimping choice

CBDCs can also stifle financial innovation by driving out private competition in the fintech space.

We can better understand this argument by considering China again.

Part of the reason China introduced the e-CNY was to reduce the influence of China’s giant fintechs Alipay and WeChat.

The pair account for more than 90% of online transactions, with US$16 trillion in value.

Pushing citizens to adopt the e-CNY will stifle Alipay and WeChat, despite the duo’s immense value to their users.

That isn’t great for innovation or consumer choice.

Alipay and WeChat become so popular because they experimented, innovated, and served their customers.

If CBDCs hinder private enterprise’s ability to innovate in the service of consumers, we can all suffer from suboptimal outcomes.

CBDCs and disintermediation

How would you like having restricted access to loans and personal credit?

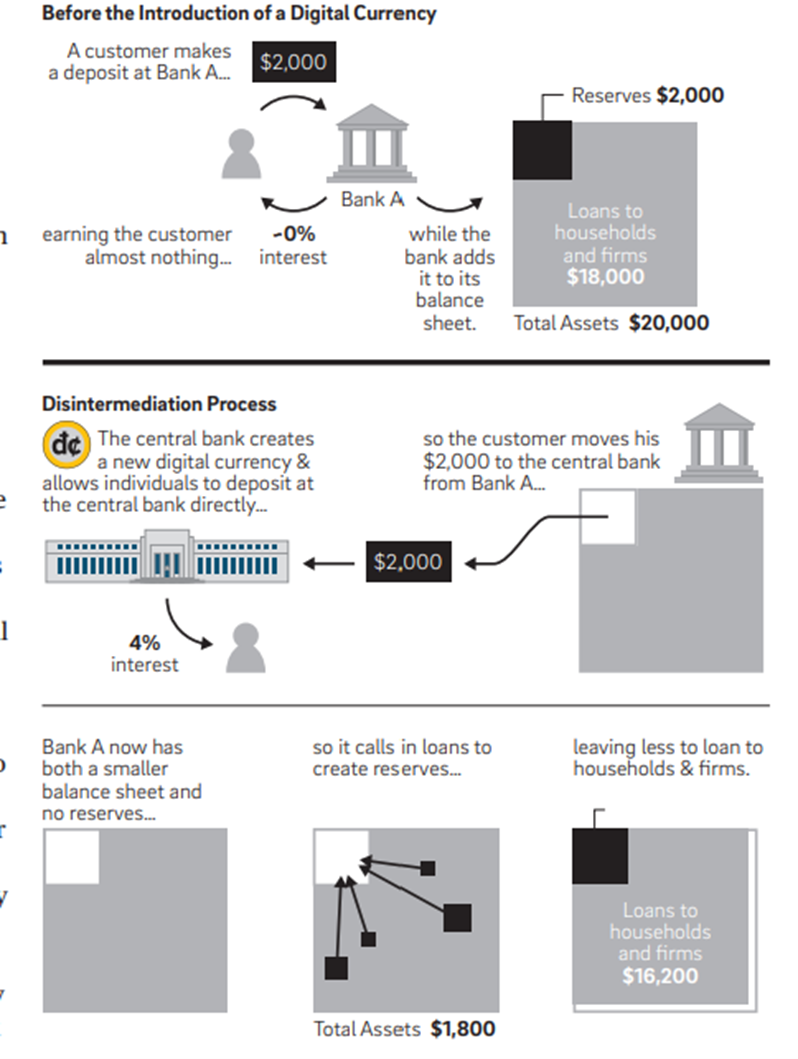

Sounds farfetched, but mass adoption of a CBDC could lead to what economists call disintermediation.

Disintermediation occurs when individuals and businesses transfer their funds from private financial institutions like big banks to an account at the central bank.

Banks rely on deposits to finance loans, a customer exodus to the central bank will shrink the pool of deposits banks can use to make loans.

As economist Daniel Sanches explained:

‘To better understand disintermediation, suppose that a central bank creates a CBDC overnight and offers to pay 4 percent per annum interest on its account balances. Right now, commercial banks in the U.S. offer a negligible, if not zero, interest rate on most retail customers’ account balances. If commercial banks do not change their interest rate strategy in response to the introduction of a CBDC, many people and firms will likely transfer their balances to a CBDC account immediately. Because commercial banks issue deposits to finance loans to households and firms, they will have to contract their loan portfolio in response to a decline in deposits, leading to disintermediation in the banking system.’

Source: Daniel Sanches

Source: Daniel Sanches

A CBDC can crowd out private bank deposits and destabilise the credit system.

Central banks will obviously argue they will seek to avoid this…but why rely on implicit trust when there’s a better guarantee — not having a CBDC at all.

So, we’ve got the prospect of digital dollars the government can track, and central banks can potentially manipulate.

We’ve got the prospect of financial instability brought on by dwindling private credit in response to individuals rushing to central bank accounts.

Who knows what else can happen?

Whatever the case, CBDCs are definitely a development you should learn more about.

Funnily enough, if you do want to learn more about CBDCs and are worried about their potential implications, we’ve just laid down our thoughts on the matter in a lively presentation.

I highly recommend you watch the briefing, as it offers a nice breakdown of all things central bank digital currencies.

Regards,

Kiryll Prakapenka