Last week, we saw the predictable pantomime that plays out whenever we get a rise in interest rates.

First, to the banks…

Within days, the interest rate on variable rate mortgages was swiftly raised by the full 25 basis points.

That works out to an extra $76 per month on a $500k loan and an extra $152 on a $1 million mortgage.

By the way, the word mortgage comes from Old French, meaning ‘dead pledge’.

And the way interest rates have risen this year, we could see a lot of people passing on a nice pile of debt to their kids.

I mean, Japan have had multi-generational mortgages for years…

Anyway, at least the rate rise was good news for savers.

Or was it…?

It all makes sense…for the banks

While banks were fast to pass hikes onto borrowers, they didn’t do the same for savers.

Of course, that meant the usual outrage from politicians, tabloid editors, and shock jocks alike.

But the major banks seem happy to ride it out.

From their point of view, it makes sense to be stingy here. After all, deposits cost them interest while loans make them interest.

Is this just pure greed then?

To a degree, yes.

Though, as I’ll show you shortly, they’d argue they’re being ‘prudent’.

It’d be easy just to indulge in the usual name calling on this — and that’s what most of the mainstream media does.

But to understand both sides of the coin here, you need to understand the mechanics of how banks work.

There’s a major misconception of how banks operate.

People think banks use deposits to make loans, that the bank sits between borrowers and savers, taking a cut on the way through.

If that was true, we’d see banks ‘competing’ for deposits in the spirit of free market competition. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be able to lend.

The net margin — the difference between borrowing and saving — would shrink to the point where uncompetitive banks would fade away.

But this isn’t how it works in one very important way.

The truth is, deposits aren’t a constraint on a bank’s ability to lend money in any way.

The mechanics here might surprise you.

For one, it all works in reverse!

Bank loans create deposits, not the other way around.

To see how this makes sense, imagine you get a $500k mortgage from the bank. That $500k is a loan for you but it’s also been sent to the bank account of the person who sold you the house.

Where did that $500k come from?

Nowhere!

It was simply new money created at the press of the button.

The bank didn’t have to check they had a pile of money ‘in the back’ to cover it.

(Note, this is actually one of the main ways by which new money is injected into the economy. Government spending through debt is the other one.)

But I hear you say, doesn’t that mean the bank can just create as many loans as they want?

I mean, if the money for these new loans doesn’t come from deposits, where does it come from?

Well, banks do have some constraints on how much they can lend, but it’s not from deposits.

It’s more related to profitability.

But I repeat, the number of deposits on the books has no bearing on how much a bank can lend out.

Instead, banks have to maintain certain regulatory capital ratios.

I won’t delve too deep into exactly what this is and how it works (you can dig in deeper here).

But basically, it’s the bank’s equity (shareholder funds contributed), plus any retained earnings (and some other reserves).

That figure is called the ‘capital base’, and you can think of it as simply the money invested by investors and any profits kept over the years (and not paid out in dividends).

This number is divided by the total number of loans the bank has outstanding (remember, loans are assets to the bank).

It’s important to mention that different types of loans are ‘risk weighted’ to account for varying risk levels.

The equation looks like this:

|

|

| Source: APRA |

Now, banking regulators set out minimums for this ratio.

The global minimum for tier 1 capital is 4.5%.

This is meant to be the funds a bank can fall back upon and use in case of major loan defaults.

Which is why banks would argue their position on savings rates is more a prudent act of capital management rather than a greedy profit grab.

But the same figure also shows you the leeway a bank has to keep growing their lending book.

And lending is the name of the game when it comes to bank profits.

A high ratio means a bank can keep lending out money without having to raise new funds. That’s good news for existing shareholders as it increases the return on equity.

In this regard, Australia’s banks are looking good…

An analysis of three different banks

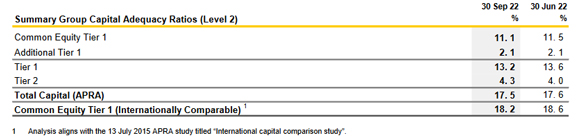

Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s [ASX:CBA] latest results from Q3 2022 show their regulatory capital position is looking good:

|

|

| Source: CBA |

These are very strong ratios with tier 1 capital at 13.2% (well above 4.5% international minimum).

This means that CBA has plenty of scope to lend more without having to raise new funds.

How about a non-Big Four bank like AMP [ASX:AMP]?

Again, these are pretty strong figures:

|

|

| Source: AMP |

Not as good as the CBA, but still with ample buffers in place to keep lending.

Here’s the thing…

Unlike the CBA, AMP’s share price has been in the doldrums for years.

But with what I think is a good turnaround strategy well underway, I’d suggest it’s worth a closer look.

AMP grew their loan book by 1.15 above the industry’s average in the first half of 2022, and the regulatory capital ratio above suggests they have room to keep doing so.

Of course, these figures aren’t static, and there are risks to continually monitor.

For example, a big recession would eat into profits — and small banks tend to do worse than big banks in such conditions.

And if enough borrower’s default, equity buffers would fall too (i.e: the ratio would fall).

That can destroy shareholder wealth.

Because the banks have to raise more money by issuing more shares, likely at a steep discount to current share prices or risk going bankrupt.

Here’s a current example of what happens when it all goes wrong for a bank…

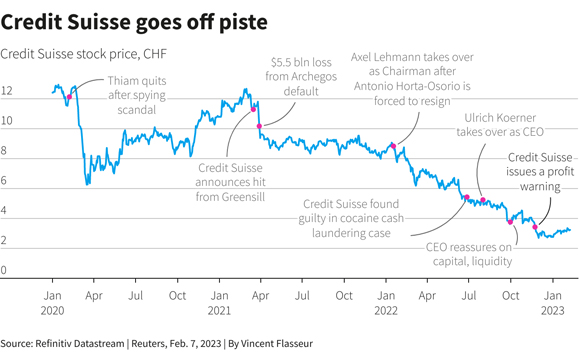

Check out the share price of Credit Suisse — a former Swiss banking high-flyer — to see how that death spiral goes:

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

You can see how a wave of big losses is affecting Credit Suisse’s regulatory capital position here (from right to left):

|

|

| Source: Credit Suisse |

The tier 1 capital ratio, though still well within acceptable bounds, fell by almost 2% over the last four quarters from 14.3% to 12.6% by the third quarter of 2022.

While the figure itself isn’t terrible, the trend is worrying.

And from recent news, things are set to get worse.

As reported:

‘Credit Suisse’s “operational performance was even worse than feared and the level of outflows quite staggering”, Thomas Hallett, analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, said in a note.

‘With heavy losses to continue in 2023, we expect to see another wave of downgrades and see no reason to own the shares.’

Swiss regulators are watching closely and it’s that regulatory capital position that is the main item to watch…

Boring but useful

Which brings in a second big risk for bank profits.

Regulatory risk.

There’s probably no two words more boring than that in the English language.

But when it comes to investing in banks, it’s essential to know the rules of the game.

That’s what regulations are.

Right now, global banking regulators are in the throes of releasing Basel III, the third iteration of a suite of new banking rules.

These rules are complex and will dictate what kind of lending banks prefer doing, as well as how much capital they need to retain in relation to outstanding loans.

The trend since the 2008 GFC has been to raise these capital ratios and if that happens again, it may mean banks have to raise more capital.

But it’s not necessarily as simple as that.

From my reading, the latest updates will heavily favour property lending by banks versus other forms of loans like business loans and credit cards.

In that case, banks might simply retarget lending to property — even more than they do now — leaving the business market to others.

That’s an idea worth mulling over and a reason small fintech stocks that focus purely on business lending — like Butn [ASX:BTN] — interest me.

Anyway, my aim today was to peel back the lid a bit on how banks really work.

I think this knowledge is useful to know as it shows you how new money comes into the system.

It also shows you how reliant banks are on the property market to keep being able to lend out money in a way that keeps their capital requirements low.

But there’s a lot more I’ve not covered today.

Next time, maybe I’ll tell you how your deposits in the bank aren’t really money anyway!

In the meantime, you’ll hear a lot this week about Jim Rickards’s new book, SOLD OUT!, which is essentially Rickards’s dissertation on the looming recession and how it will drastically impact the working and middle class.

In it, Rickards outlines the ‘mistake’ he thinks central banks will make to try and curb the surging inflation we’ve been facing in recent years. Fair warning, things could get a whole lot worse…

Until then,

Good investing,

|

Ryan Dinse,

Editor, Money Morning