In his book Zero to One, Silicon Valley titan Peter Thiel wrote about truths hiding in plain sight — powerful truths we don’t see even though they are right in front of us.

Such truths can make for great business and investment opportunities.

Here’s Thiel giving examples of these ‘open secrets’:

‘Great companies can be built on open but unsuspected secrets about how the world works. Consider the Silicon Valley startups that have harnessed the spare capacity that is all around us but often ignored. Before Airbnb, travelers had little choice but to pay high prices for a hotel room, and property owners couldn’t easily and reliably rent out their unoccupied space. Airbnb saw untapped supply and unaddressed demand where others saw nothing at all.

‘The same is true of private car services Lyft and Uber. Few people imagined that it was possible to build a billion-dollar business by simply connecting people who want to go places with people willing to drive them there. We already had state-licensed taxicabs and private limousines; only by believing in and looking for secrets could you see beyond the convention to an opportunity hidden in plain sight. The same reason that so many internet companies, including Facebook, are often underestimated—their very simplicity—is itself an argument for secrets. If insights that look so elementary in retrospect can support important and valuable businesses, there must remain many great companies still to start.’

While Thiel’s idea focuses on individual companies, what if we could apply it to whole industries?

Is there an industry operating as an open secret?

I think semiconductors are worthy candidates. Their colossal prevalence in much of the world’s key functions is greatly underappreciated.

The new oil

China’s brisk economic growth over the last few decades has made it an economic barometer of resource consumption.

China’s industrial activity often has a powerful effect on commodity prices.

Beijing in a downturn? Iron ore and oil will likely trend lower.

Beijing pushing hard on EVs? Lithium is likely to trend higher.

And so on.

So we can look to China’s consumption for clues — for open secrets.

What does China spend the most money on importing?

It’s not oil.

No, China now spends more money annually on importing semiconductors — or chips — than it spends on importing oil.

As Chris Miller, author of the recently published Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, neatly put it: ‘Beijing is more worried about a blockade measured in bytes rather than barrels.’

|

|

|

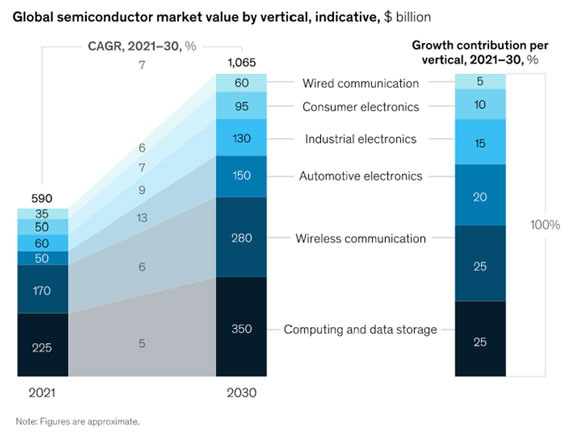

Source: McKinsey & Company |

Semiconductors run this world

What’s a world without oil?

Marooned, localised, slow, dimmed.

But what’s a world without semiconductors?

A world plunged back five decades.

Semiconductors may just be the open secret people overlook — their importance is disproportionate to their profile.

As Miller explains:

‘We rarely think about chips, yet they’ve created the modern world. The fate of nations has turned on their ability to harness computing power. Globalisation as we know it wouldn’t exist without the trade in semiconductors and the electronic products they make possible.’

Chips are the foundation of the modern world (emphasis added):

‘Today, thanks to Moore’s Law, semiconductors are embedded in every device that requires computing power — and in the age of the Internet of Things, this means pretty much every device. Even hundred-year-old products like automobiles now often include a thousand dollars worth of chips. Most of the world’s GDP is produced with devices that rely on semiconductors.’

Without chips, we lack the hardware of modern society. But while semiconductors are fundamental, the industry is highly volatile, despite its importance.

The boom and bust cycle of the semiconductor industry

Chipmakers and suppliers operate in a cutthroat environment, and the industry is highly prone to boom-bust cycles.

Given the close link between semiconductors and the economic activity they make possible, the industry is exposed to business cycles.

And no wonder.

Chris Miller reported that last year, the chip industry produced ‘more transistors than the combined quantity of all goods produced by all other companies, in all other industries, in all human history’.

At such a scale, getting inventory right is hard, and any unexpected economic downturn hurts.

A 2022 Deloitte report noted:

‘Historically, every shortage has been followed by a period of oversupply, resulting in falling prices, revenues, and profits. The cycles of the past 25 years have been like a roller coaster that no human would voluntarily ride. Between 1996 to 2021, year-over-year chip revenue soared by more than 20% no fewer than seven times. It also plunged by almost 20% year-over-year five times over the same period. The drop was especially stomach-churning in 2001, which saw revenues fall by nearly 50% from a year earlier.’

We can see this cycle playing out right now.

The widely followed Philadelphia Semiconductor Index was down nearly 50% from its peak by mid-October, well underperforming the S&P 500:

|

|

|

Source: Financial Times |

And in recent weeks, big chipmakers came out with revenue downgrades.

Mobile chipmaker Qualcomm cut revenue guidance by 25%.

CFO Akash Palkhiwala admitted that ‘it’s kind of an unprecedented change over a short period of time. We went from a period of supply shortages to demand declines’.

Qualcomm isn’t alone. As the Financial Times reported earlier this week, AMD and Intel have both cut guidance, with Intel signalling thousands of job layoffs.

But while the chip industry cycles another downturn, the long-term outlook remains clear.

We can’t live without chips.

We’ll need more chips as our populations grow and technologies advance.

The industry is only set to grow in the long term.

As the Deloitte report I mentioned earlier concluded (emphasis added):

‘Taking the long view, however, up and to the right has been the consistent trend. Global semiconductor sales were up by 25% in 2021 despite ongoing shortages, and they are predicted to rise a further 10% to US$606 billion in 2022. This is almost ten times greater than the 1990 figure of US$58 billion. When measured as a percentage of global GDP, 2021 chip revenues were 130% larger than they were 30 years ago. Given the continuing tail wind of demand from the digital transformation of every aspect of life, semiconductor revenues look to keep gaining share of global economic output, whether chips are scarce or abundant.’

The age of scarcity looming for commodities

Speaking of scarcity, my new colleague James Cooper — a trained geologist and commodities expert — has just published a report on what he sees as a powerful scarcity-driven opportunity emerging in the resources sector.

In fact, James is holding a free event tomorrow outlining his arguments about the looming ‘Age of Scarcity’ and the potential commodities boom right here on the ASX.

I highly recommend you register for the event.

You can do so by clicking here.

Until next week,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

For Money Morning