Journalists have the Five Ws. Who? What? Where? When? Why? Five questions to find the truth.

Investors only need one.

What’s not priced in?

Searching for the answer will direct you to all the right areas.

The reason is simple.

Investing is about differentiated insight. Be right and set yourself apart from the crowd.

You don’t want to join the crowd. You want the crowd to join you.

The market is a giant decentralised bookie.

It assigns odds to countless outcomes — recessions, rallies, individual stock performance…

And like legendary punter Steve Crist said, the path to consistent profit lies in exploiting the ‘discrepancy between the true likelihood of an outcome and the odds being offered’.

In this episode of What’s Not Priced In, Greg Canavan takes us through why the market is still underpricing the risk of recession.

The likelihood of recession is not certain.

But it’s higher than the bookie thinks.

US valuations stretched

US stocks rallied this fortnight. Some attributed that to the Fed’s pause. Greg pointed to previously oversold positions instead.

At the end of October, the US stock market was heavily oversold.

The bounce was inevitable.

The question is, can the rally continue?

Greg is doubtful.

The problem is valuations.

The S&P500 is trading on a forward earnings yield of about 5.6%. This assumes earnings per share rise over 10% in FY24.

Is that likely?

For Greg, this is a low probability outcome.

Not to mention that the current US 10-Year bond yield is hovering at about 4.60%. Meaning the equity risk premium is slim.

When the stock market yields only ~1% more than the risk-free rate, there’s little reward to compensate for the risk.

So US stocks remain stretched.

RBA is not Superman

German philosopher Immanuel Kant asserted years ago that ought implies can. Responsibilities, to Kant, entail a capacity to fulfil them.

Responsibilities are like mandates.

And the Reserve Bank’s mandate is to keep the price level steady and unemployment low.

The RBA ought to. But can it?

As we discuss in the episode, sometimes not.

The RBA can’t do much about the price of electricity, housing, or petrol.

Entrusted with keeping inflation under control, the RBA’s mandate sometimes outruns its capacity.

The RBA is not a superhero. Let’s lower our expectations of its powers.

Not to mention that just because the RBA’s job is keeping prices stable doesn’t mean state and federal governments can’t help.

State and federal governments can ease inflation, too.

Often, they choose not to.

More on that below.

Hansard surfing

Ian McEwan’s The Children Act was inspired by reading family court judgements.

‘It was the prose that struck me first. Clean, precise, delicious. Serious, of course, compassionate at points, but lurking within its intelligence was something like humour, or wit, derived perhaps from its godly distance, which in turn reminded me of a novelist’s omniscience.’

Hansard transcripts of parliamentary testimony by RBA officials don’t hold the same literary promise. But they do have uses.

Fronting a hostile audience, Reserve Bank officials are often more forthright than their written communiqués.

Take this testimony earlier this year from former governor Philip Lowe.

Asked if governments can ‘help or hinder’ fight inflation, Lowe said ‘in principle they can’:

‘Decisions that are made by the parliament can affect inflation in at least three broad ways. A more restrictive policy stance — let me be clear about that; that involves higher taxes or less government spending — would mean less aggregate demand in the economy and less inflation. The second thing governments can do is structural reform that increases the supply side of the economy so it grows more quickly, so a given level of aggregate demand doesn’t put upward pressure on prices —so it can do things on the structural front. The third thing governments can do is intervene in specific markets to reduce price pressures; we saw an example of this recently in the electricity market…’

We can see that in Australia with house prices.

Despite a dizzying rate hike cycle, Australian home values are rising again.

As Greg stressed, this has little to do with monetary policy.

What’s funny is that RBA officials know this.

In her recent appearance before a parliamentary committee, Muchele Bullock was grilled about rising rents.

A senator wanted to blame the central bank. Bullock pushed back. The problem, she said, was lack of supply:

‘The problem with the rental is not interest rates. The problem is that demand for rental properties is too high relative to the stock of rental properties. Immigration is adding to demand for properties. Which adds to demand for rental properties, which adds to pressure on rents.’

Lowe was even blunter in his final parliamentary showing:

‘The supply side of the [housing construction] market is not flexible — let’s put it politely — and it’s not flexible largely because of regulation, planning, zoning, developments and charges. So there is a lot of regulation there which is affecting the flexibility of the supply side of the housing market, and the result of that, with strong population growth, is rising housing prices and rising rents.’

And that leads to a puzzle.

Population, housing stock and catch-22

How do you ease inflationary pressures caused by population growth without doing anything about immigration intake?

We just mentioned housing.

If immigration policy remains unchanged, rents and home prices from population growth can only slow with more supply.

More housing, more properties, more rentals…

But you can’t have more housing without more spending.

Michele Bullock last month said as much before the Economics Legislation Committee:

‘In many of the states, particularly in New South Wales and in Victoria, there is infrastructure spending, and the fact is that we need spending on infrastructure. We’ve got a growing population, and we need that spending on infrastructure. You can’t just halt these things.’

Spending on infrastructure boosts demand. For workers, materials, equipment…

In a tight labour market, rising demand boosts wages.

Wages is a key component of services inflation.

And what is the Reserve Bank worried about most? Slow progress with taming services inflation.

Looks like we’re in a pickle.

What else caught my eye this week

- US companies are using interest arbitrage to lower their interest payments. The Economist reported earlier this week:

‘Many firms issued long-term debt when rates were low, and so continue to enjoy low financing costs today. Net interest payments by America’s companies have actually fallen this year because the interest they earn on the cash they keep to hand has risen faster than the cost of servicing their debts.’

Looks like duration risk has its benefits!

- NAB’s chief executive Ross McEwan said mortgage competition is hurting margins. The competition is leading to ‘some of the thinnest mortgage margins I’ve seen in Australian banking.’ McEwan also said the RBA’s cash rate ‘appears to be at or near peak levels and it seems likely that Australia will avoid a pronounced economic downturn.’ What about a non-pronounced economic downturn?

- Oil demand in the US is about to hit a 20-year low, according to the US Energy Information Administration:

‘Although the U.S. population has grown in recent years, the nation’s gasoline consumption has increased more slowly in comparison, meaning U.S. gasoline consumption has been decreasing on a per capita basis. We forecast the average person in the United States will consume 402 gallons of gasoline in 2024, down from a peak of 475 gallons per person in 2004. Because of lower per capita gasoline consumption, we forecast overall U.S. gasoline consumption to decline in 2024 to 8.83 million barrels per day (b/d), from 8.88 million b/d in 2023 and down from the 2019 pre-pandemic average of 9.31 million b/d.’

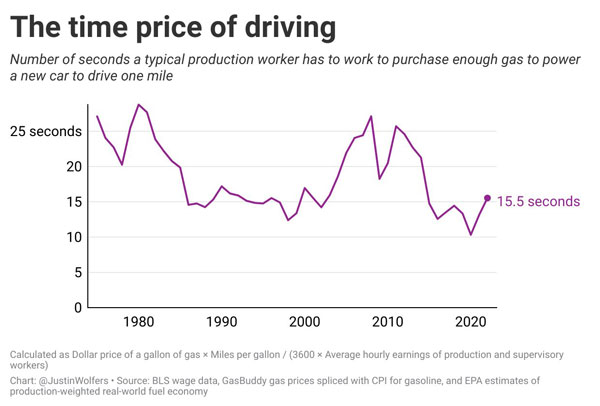

- Ever wondered how many seconds a typical production worker has to work to buy enough fuel to power a new car to drive one mile? Well, here’s the answer:

| |

| Source: Jason Wolfers |

On a final note, thank you to everyone who came down to Fat Tail’s get-together in Melbourne. It was a pleasure meeting readers (and podcast viewers!).

Despite bashfulness, I enjoyed chatting to you all! Hope it was reciprocated!

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Fat Tail Daily

Comments