Surprise, surprise, surprise…Fitch Ratings downgraded its US debt rating from AAA to AA+.

Is the US at risk of default?

No.

If the US Government needs money to meet its obligations, it’ll be printed. But, as we now know, too much money printing can lead to inflation.

A future filled with inflationary waves is a very real prospect…like it was in the 1970s. And that’s not good news for holders of debt issued at lower rates or share investors.

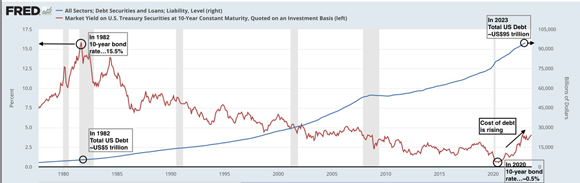

Over 40 years ago, it took a US 10-year bond rate of 15.5% to slay the inflationary dragon.

In the early 1980s, total US debt (private, corporate and public) was around US$5 trillion.

As rates (the cost of debt) trended down, the volume of debt trended up.

|

|

| Source: FRED |

In 2020, the US 10-year bond rate went to a low of just…0.5%…that’s 15% lower than it was in 1982.

Obviously, when the cost of borrowing is SO cheap, resisting the temptation to gear-up is almost impossible. Since 2020, the US debt has gone from US$75 trillion to US$95 trillion.

The math is staggering…over the past four decades, the US debt burden has increased by US$90 trillion.

However, the days of cheap money appear to be over. The cost of debt is rising, which explains why Fitch has concerns over a blowout in future Federal budgets.

How will successive administrations be able to afford the interest bill WITHOUT printing?

The answer is…they can’t.

The prospect of persistent global inflationary pressures is unnerving bond markets. Pressures are building.

This is why the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has started taking steps to be less controlling with its yield curve control.

The problem is that the BoJ has distorted market pricing for so long that there is bound to be a raft of unintended consequences when the pressure valves are released.

Heed the wisdom of James Grant

One of those who identified this risk early was the esteemed James Grant.

For those not familiar with James Grant — founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer — here’s a little overview.

His career in journalism began at The Baltimore Sun in 1972. He went to Barron’s in 1975. Then in 1983, he founded Grant’s Interest Rate Observer — a twice-monthly publication.

Grant (now aged 77) — with a body of work spanning four decades — has proven to be an astute reader of markets and fiercely independent in his views.

In 2008, James Grant published Mr Market Miscalculates: The Bubble Years and Beyond.

The book was a collection of his Grants Interest Rate Observer essays from the mid-90s up until 2008.

On 24 November 2008 (after the Lehman Moment), The Financial Times published a review of Grant’s book. To quote from the article (emphasis added):

‘If Grant could see what was happening this clearly, and warn of it in a well-circulated publication, how did the world’s financial regulators fail to avert the crisis before it became deadly, and how did the rest of us continue to make the irrational investing decisions that make Mr Market behave the way he does?’

With a career spanning 50 years, James Grant is one of the most respected voices in the investment business.

Japan is perhaps the most important risk in the world

On 17 January 2023, James Grant was interviewed by The Market NZZ.

The title of the interview is…‘Japan Is Perhaps the Most Important Risk in the World’.

The title gives it away.

Grant thinks Japan could be the Lehman Moment that blindsides financial markets.

I strongly urge you to read the whole transcript of the interview.

As a teaser, I’ll share a few key points with you.

1. The era of lower rates — lasting almost 40 years — is over.

To quote (emphasis added):

‘If the past is prologue and if the great bond bull market is over, then on form, we are looking at what could be a very prolonged and perhaps gradual move higher in interest rates.’

What asset class performed exceptionally well over these four decades of descending interest rates?

Shares.

The Dow Jones went from 1000 points in 1982 to 36,000 points in 2022.

What will ‘a very prolonged move higher in interest rates’ mean for shares in the coming years/decades?

A lot less growth than we’ve become accustomed to.

2. When it comes to inflation, is the Fed ‘the solution or the problem’?

To quote (emphasis added):

‘I think that we have not seen the last of this inflationary outburst. But one needs to be quite humble in the face of something that very few central bankers anticipated or even could have imagined. It wasn’t just that the Fed didn’t predict it, but when the Fed saw it, when it saw the whites of inflation’s eyes, it still couldn’t believe it and continued with its QE program until the end of March 2022.’

3. Why we should be looking at Japan.

To quote (emphasis added):

‘I think Japan is perhaps the most important risk in the world, not least because it is among the least discussed risks, certainly in the Western press. Mostly, it’s very much an afterthought. The risk is this: Every business day, the Bank of Japan is spending tens of billions of dollars worth of yen to enforce Governor Kuroda’s yield curve interest rates suppression program.

‘To put this into perspective: In the UK, when the little crisis over liability-driven pension investing in late September happened, the Bank of England spent around $5 billion. The BoJ does that before breakfast.’

4. Finally, in the end, something ALWAYS gives.

To quote (emphasis added):

‘Governor Kuroda, whose term is up on 8 April, insists that yield curve control is here to stay. But to us, Japanese interest rate policy resembles the Berlin Wall of the late Cold War era, a stale anachronism that must sooner or later fall.’

These are just snippets from an excellent interview with a brilliant thinker.

James Grant goes into far more detail on why Japan is the risk no one is really looking at, and what the potential ramifications will be for global financial markets if (or, when) the BoJ finally relinquishes control over the yield curve.

Please set aside some time to read (and, as I did, re-read) the transcript of this interview. It’ll be time well spent.

With either option — persistently high rates OR a Lehman Moment — there are no good outcomes here.

The worst of times for retirement plans

In my opinion, this is the worst of times for people to be making retirement plans. Anchored to the belief of ‘what has been will continue to be so’, financial plans will be made based on the performance of markets over the past 40 years.

However, the conditions that created those returns NO LONGER exist. Debt levels are beyond anything we could ever have imagined. The 40-year downward trend in rates is reversing. US shares are trading on nosebleed multiples.

We now have to deal with the consequences stemming from this extraordinary 40-year experiment in debt-funded growth.

A future of higher inflation. Share markets zigging and zagging their way to no meaningful gains. Rising interest rates. Debt defaults. Surging commodity markets.

These are not being factored into any of the financial plans I’ve seen in recent times. Pressures are building.

We are on the cusp of an almighty shift in how markets function. Don’t be blindsided by what is hiding in plain sight.

Until next week.

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia