Future demand for commodities is approaching and it’s not coming from one direction.

Firstly, there’s the obvious one, a green energy transition; set to unleash a multi-fold boost for specific critical metals like nickel, copper, zinc, and lithium.

Then there’s the imminent re-activation of China’s property market as it emerges from a two-year COVID lockdown, boosting demand for coal, iron ore, and copper.

But let’s not forget about the other factors too…Biden’s US $1 trillion Infrastructure Bill was recently passed by Congress. Described as a ‘once-in-a-generation’ investment in the nation’s infrastructure and competitiveness.

Just think of all the metal needed to rebuild bridges, ports, hospitals, roads, and railways for the world’s LARGEST economy.

This is sorely needed in the US. If you’ve ever travelled there, you’ve probably noticed the infrastructure looks tired and broken in many parts of the country…we have it rather good in Australia by comparison.

There’s also the inflation effect; as the purchasing power of cash and bonds continues to erode, investors will look to ‘real asset’ investments to preserve their wealth.

But don’t forget the ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative either, the $5 trillion plan where China intends to link its rail, road, and shipping connections through Asia, Africa, and South America…or has that been permanently shelved thanks to COVID? I don’t think so.

It’s the culmination of all these demand-driven factors that separates this coming boom from the last boom, which was fuelled exclusively from Chinese growth.

However, it’s all small fry compared to the main issue at play here…SUPPLY.

The impending shortage of commodities that no one seems to recognise.

No discovery means NO SUPPLY

You’re probably aware of the sharp boom-to-bust nature of commodities.

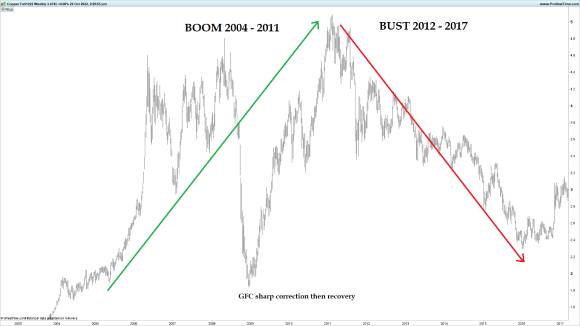

Most market participants accept that our ‘once-in-a-generation’ boom lasted from the early 2000s to 2012. What followed was a sharp drop in commodity prices, reaching a final low around 2017.

I have used a chart of copper futures to remind you how it played out:

Historical chart — boom-to-bust copper futures:

|

|

| Source: Pro Real Time |

It’s no surprise that high-risk ventures such as exploration activity tend to ebb and flow on the back of commodity prices.

It means there is a direct relationship between new discovery and rising prices.

It’s why boom periods are critical in fuelling exploration and replacing old mines with depleting reserves, the very mines that were discovered in prior booms.

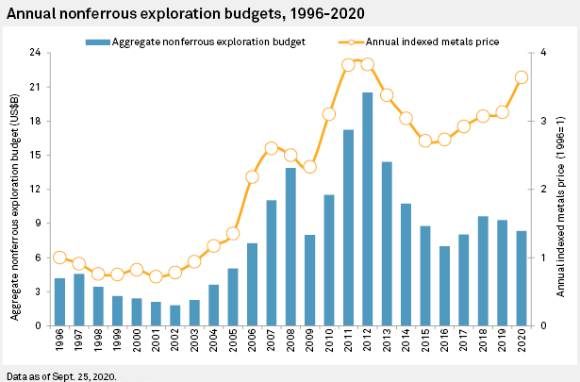

The graph below from S&P Global Market Intelligence demonstrates the strong correlation between exploration activity and rising commodity prices (during the last boom):

|

|

| Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence |

Notice also the sharp fall in exploration budgets on the back of falling prices…not surprising.

However, look further to the right and the supply/demand rule that has dictated commodity prices for eons seems to be facing an anomaly.

You see, from 2017, when commodity prices began to recover and trend upward, there has been no subsequent increase in exploration.

The graph from Market Intelligence actually shows a decrease in spending as prices rose into 2020 (pre-pandemic).

Perhaps, investors burned by the effects of the last boom cycle and subsequent bust, have shunned exploration, even as commodity prices rise.

Who knows the exact reason, but it is a concerning trend…without additional discovery in the pipeline, we’re totally reliant on existing resources to meet current (and future) demand.

Until meaningful investment finds its way BACK into exploration, there’s very little chance of making a significant discovery.

This is especially troubling given that a mine is a depleting resource, often losing productivity further into its life cycle as companies exhaust the highest-grade ore first.

Overall, it spells trouble for future supply.

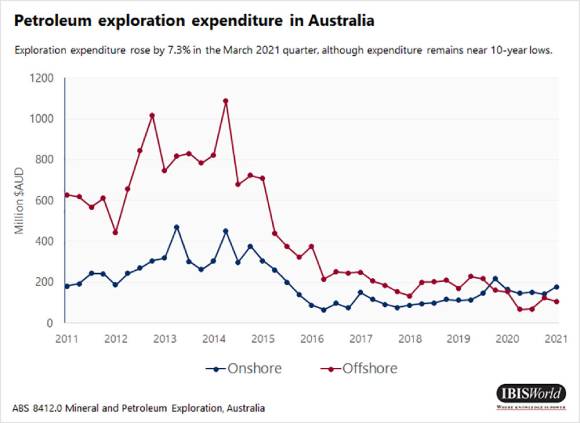

The situation is even more stark when we look at the oil and gas industry. I’m sure you don’t need any reminders of the rising cost to fill up your car these days.

But have rising prices at the petrol station helped stage a comeback in exploration expenditure?

It doesn’t seem that way according to data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, with expenditure sitting at a 10-year low, see for yourself below:

|

|

| Source: IBIS World (data ABS Australia) |

This isn’t really surprising. What company in its right mind would allocate precious capital toward discovering new oil wells right when the government is on a war path to kill your business?

An exceptionally low appetite for exploration, even as commodity prices rise, plays into a compelling case for future undersupply.

This WILL have dire consequences when we consider our future energy requirements.

A poorly planned energy transition

Critical underinvestment in oil and gas exploration means the world has already shut the door on fossil fuels.

Worryingly, this poses an immediate danger to the world’s energy security when we’ve simultaneously cut back on mineral exploration for critical metals needed in this ‘Great Green Energy Transition’.

Take copper, for example, a critically important metal. It’s said electric vehicles need a three-fold increase in copper content versus a conventional vehicle.

It is also a key metal in transporting renewable energy to homes and businesses.

But according to S&P Global Market Intelligence, new copper discoveries have fallen by at least 80% since 2010.

This doesn’t bode well for utility networks attempting to install a vast network of ‘copper’ infrastructure to support the delivery of green power.

It doesn’t look good for you or me either!

Copper is set to play a pivotal role in our green energy transition, yet this hasn’t corresponded with an uptick in exploration, despite rising prices.

This is the situation on the ground for most of the world’s critical metals; ageing mines with rapidly depleting resources continue to provide just enough metal to supply current demand.

In reality, though, these old mines hide the underlying supply issue.

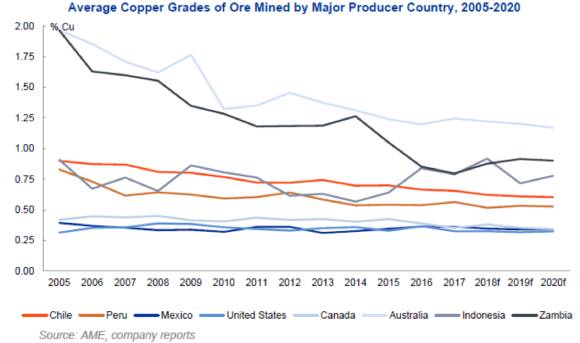

For example, Chile, the world’s largest copper producer (accounting for around one-quarter of the global supply) still relies on decades-old low-grade ‘porphyry’ deposits. Lower grades mean higher production costs and push operations to the edge of viability.

In ageing operations, like those in Chile, miners are forced to extract the low-grade ‘fringes’ of the pit and run ‘low-grade’ waste through processing facilities.

These are short-term solutions that will fail to meet even a small uptick in demand let alone a future multiangled boom I highlighted above.

It’s not isolated to Chile either.

The trend of lower copper grades is occurring across all major producing countries. You can see for yourself, below:

|

|

| Source: AME |

In Australia, average copper grades have more than halved since the beginning of the last mining boom!

A failure to find new reserves paints a bleak picture for our ‘Great Energy Transition’.

Severe underinvestment in critical metals over the last 10 years means we simply don’t have the raw materials available to build solar panels, electric vehicles, wind turbines nor the infrastructure to transport that energy.

So, what’s our back-up plan?

There isn’t one…by cutting off investment in oil and gas exploration, we’ve wrung the death bell on future supplies for fossil fuels.

If capital is deployed to exploration will this avert a coming crisis?

Once the global economy DOES wake up to the enormous investment required to bring additional resources online, it WILL be far too late.

Why? It takes at least five years to make a meaningful discovery.

But another layer to this problem…the severe downturn that followed the China-led mining boom caused mining professionals to leave the industry for good.

The bust that lasted from 2014–18 meant that leading geologists were no longer in the game of making new discoveries…the more experienced folk took early retirements, while others shifted into more stable careers.

On top of this, universities closed the doors to mining engineering and geology degrees. Simply staggering for a country so reliant on resources for GDP growth!

The full consequences of a 10-year underinvestment in exploration are yet to play out.

A massive gap in supply is looming. There’s a well-known time lag of at least 5–6 years to make the initial discovery.

With dwindling talent, that is assuming the discoveries are made in the first place.

Add to that a further 2–3 years to bring that discovery into production and we have a real problem.

The solution for you…buy companies that already hold valuable resources before the impending supply crunch is understood by the wider audience.

Greg Canavan’s ‘Crude Awakening’ is your starting point…accumulate the best oil and gas assets now, so you can profit while the rest start to comprehend the implications of a world without an endless supply of commodities. Read his new report by clicking here.

Until next week.

Regards,

|

|

James Cooper,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia