We’re well into the campaign for the 2022 Federal Election, and debate is running hot on housing affordability.

It’s touted in the media as the key to ‘the Great Australian Dream’, i.e. the apparent right of everyone to own their own home with ‘a backyard and picket fence’.

Except that’s not the Great Australian Dream at all.

Having worked in the property market in Australia since arriving from the UK some 15 or so years ago, I can confirm that the Great Australian Dream is to own an investment property or two and get wealthy from the so-called ‘capital gains’.

This is nature’s free lunch.

Nothing has changed since the classical economist John Steward Mill quipped: ‘Landlord’s grow rich in their sleep, without working or economising.’

‘The ordinary progress of a society, which increases in wealth, is at all times tending to augment the incomes of landlords; to give them both a greater amount and a greater proportion of the wealth of the community, independently of any trouble or outlay incurred by themselves.’

Born in 1806, John Stewart Mill is remembered as:

‘…the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the nineteenth century.’

In 1848, he published one of the most prominent textbooks on economics in the 19th century: Principles of Political Economy — cementing his reputation as a leading public intellectual.

Extending on the ideas set out by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, Mill employed concepts that have been written out of today’s economic narrative.

Those that conflate land and capital — virtual opposites — while failing to distinguish between income that is ‘earned’ and the economic surplus that disproportionately flows to those that ‘love to reap where they never sowed’.

This process is best set out in Mason Gaffney’s book The Corruption of Economics.

Overtime, ‘land’ and ‘unearned income’ were deliberately written out of the university economics courses and textbooks.

The three factors of production were replaced with just two — labour and capital.

Land disappeared from view.

When we talk about increases in land value today, it’s termed ‘capital gains’. Except, real capital doesn’t gain.

Capital is manmade — it depreciates in value with wear and tear.

Unlike land, capital’s supply can be increased with competition.

The only exception is when the owners of capital are granted monopoly power — such as taxi licences, for example.

In contrast, land is fixed in location and therefore, fixed in supply.

Taxes on capital reduce its supply and so distort economic activity.

However, taxes on land cannot reduce its supply.

They merely reduce its value — falling on the landowner and stripping away the unearned gains that would otherwise be privatised.

For this reason — and others — a land tax is the most hated tax.

You can’t avoid it, hide from it, or ship it overseas.

Therefore, conflating land with capital enables large landowners and their financiers, to argue for lower taxes on capital — and therefore lower taxes on land.

Consequently, the economic rent from land becomes ‘income’ rather than ‘unearned income’, and our cities become Monopoly boards enriching the rentiers whilst impoverishing the tenants.

There’s been a lot of discussion that the election could slow the property market.

Discourage people from chasing the Aussie dream of gaining wealth through property.

But in all honestly, there’s no need to worry.

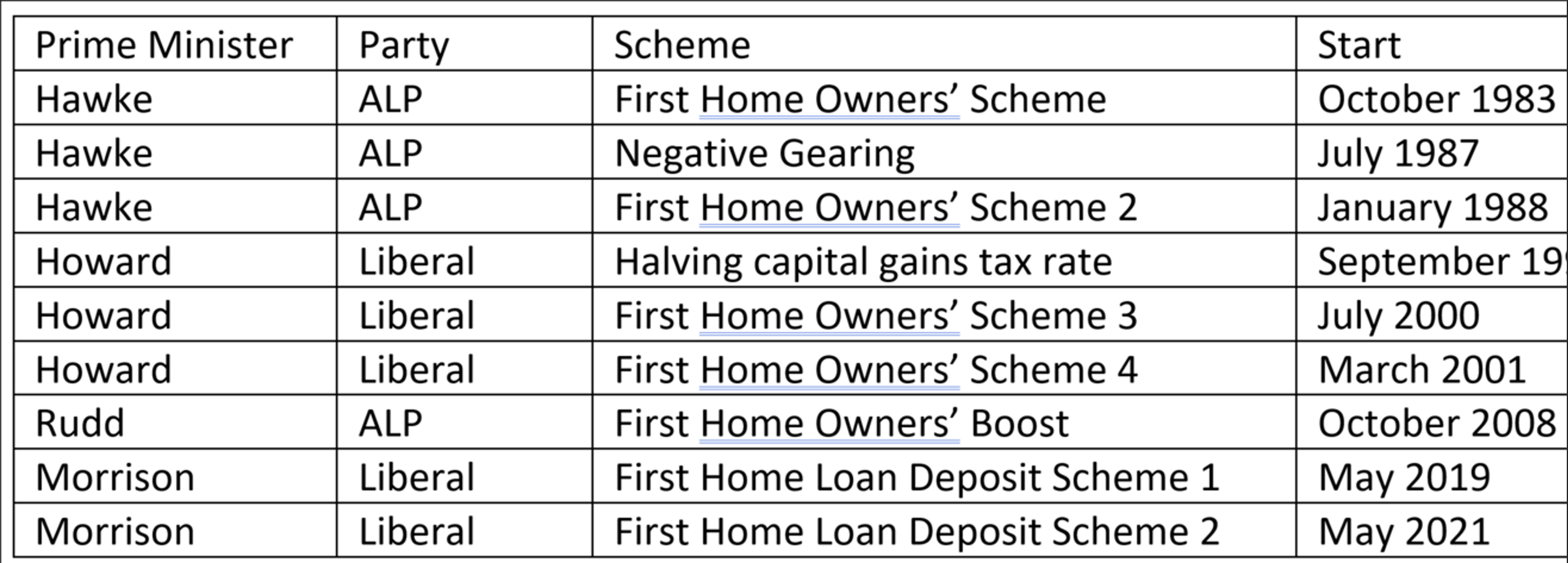

Both Liberal and Labor have actively worked to decrease homeownership rates over the years by pouring money into the property market through grants to buyers and tax breaks to investors.

A handy table demonstrating as such, flew into my inbox this week from Professor of Economics Steve Keen:

|

|

As Keen goes on to note:

‘Pumping government money into an overheated market has actually made things worse. You might as well have firefighters putting out fires with gasoline.

‘Remember the Australian dream of home ownership? That’s fast disappearing. In 1998, 43% of Australians owned their homes outright. Now that’s slumped to 30%.

‘30% had mortgages and 18% rented from private landlords. Now 37% have mortgages, and 27% are renters. Australia’s growth industries are debtors and tenants.’

In truth, the only way to create an affordable housing market would be to reduce the cost of land — and a broad-based land tax is the most effective way to do so.

As it is, the policies that encourage Aussies to gain wealth through property speculation will continue no matter which party gains power.

There’s little point fighting the system. Most correctly conclude they’re better off learning how to take advantage of it.

And the best way to do that is to sign up to Cycles, Trends & Forecasts. You can learn more here.

Best wishes,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia