No doubt you’ve been shaking your head at those Europeans and their latest self-inflicted wounds. The whole continent seems to have gone mad, again. And their energy transition is just the tip of the iceberg. But what a tip it is!

The new geopolitical mess came about because of the Europeans’ previous attempt to transition their energy system, from dirty coal to comparatively clean gas. Unfortunately, they decided to rely on Russian gas in the face of repeated Russian aggression in Eastern Europe.

Indeed, not so long ago, the Germans were busy laughing at Donald Trump, who warned them about their reliance on gas from a geopolitical opponent.

Now Germany is stuck buying Russian gas while funding Ukraine’s war against Russia. To be clear, German money is paying for the Russian artillery shells landing in Ukraine, and Russian gas is being used to manufacture the German artillery shells landing in Ukraine.

Well done.

But it may yet get worse. And, this time, Australia has signed up for the latest self-delusions.

It all comes back to the very first thing your high school economics teacher tells you. Scarcity is the idea that human wants are infinite, but the resources to meet those wants are finite. Economics reduces to how much we can produce to meet our wants, and how they’re apportioned between us.

Saving the planet from carbon dioxide, it turns out, is rather resource intensive. But governments and scientists, in committing to net zero, simply assumed this problem away and focused solely on what they want instead.

In their plans for meeting net zero, governments and scientists presumed the resources needed to achieve net zero will be available on global markets. They declared an outcome of net zero without asking how it’ll actually happen given the scarcity of resources to meet that demand.

Simon Michaux, a former miner and current energy systems researcher at the Geological Survey of Finland, recalled his time at the European Commission meetings to discuss the energy transition in the following way:

‘So the people in Europe who are talking about resource security, critical raw materials map, and the circular economy, they are doing it in the context of “let’s just buy everything off the market”. […] Well we’ve got the money, and while we’ve got the money, we’ll just buy the stuff and that’s the end of it. […] Not our problem.’

Michaux points out that this is the natural policy position of an economy that does very little mining itself. They currently presume natural resources will be available, and so presuming this will remain true is consistent. But the strategy didn’t work out very well for the EU when it came to Russian gas last winter…

You might think that policymakers have recently learnt the hard way why they should not rely on geopolitical rivals for their energy security. And yet, net zero is leading us down the same path, if not worse.

Alongside Russia, China is the West’s other key rival in geopolitics. How ironic, then, that shifting to green energy means a growing reliance on China. And not just for a fundamental part of the supply chain such as energy, but, for…well, pretty much all of it.

Whether it’s mining resources, refining them, or manufacturing the goods needed for net zero, China dominates green energy from start to finish. This means the green energy transition puts us at the mercy of China to a far greater extent than Europe’s reliance on Russian energy.

The Manhattan Institute’s Mark Mills points out how this compares to oil today:

‘China enjoys a market share of global energy minerals and refining that is more than double OPEC’s market share in oil markets.’

Olivia Lazard studies the geopolitics of climate and has a background in conflict zones. She explained to a TED Talk audience how severe this issue is:

‘The World Bank tells us that, with the current projections, global production for minerals such as graphite and cobalt will increase by 500% by 2050, only to meet the demand for clean energy technologies.’

Of course, they don’t explain how this is possible, but don’t let me interrupt the real point Lazard goes on to make:

‘Now let’s look on the supply side. That’s where a lot of really interesting things are happening. Who currently exploits and processes minerals, and where deposits to meet future demand are located, tell us exactly how the transition is going to change geopolitics.

‘So if you look at a material such as lithium, countries like Chile and Australia tend to dominate extraction, while China dominates processing. For cobalt, the Democratic Republic of Congo dominates extraction while China dominates processing. For nickel, countries like Indonesia and the Philippines tend to dominate extraction while China dominates processing. And for rare earths, China dominates extraction while China dominates processing.

‘I’ve just said China a lot, didn’t I? Well that’s because China skilfully leveraged its geoeconomic rise to power over the last two decades on the back of integrating supply chains for rare earths from extraction to processing to export.

‘We tend to point fingers at China today for not going fast enough on its own domestic energy transition, but the truth is that China understood already long ago that it would play a central role in other countries’ transitions. And it is. The EU, for instance, is 98% dependent on China for rare earths. Needless to say, this puts China in a prime position to redesign the global balance of power.’

Lazard points out that this dramatically underestimates China’s stranglehold given its geopolitical sway in places like Africa, which is, of course, not a coincidence.

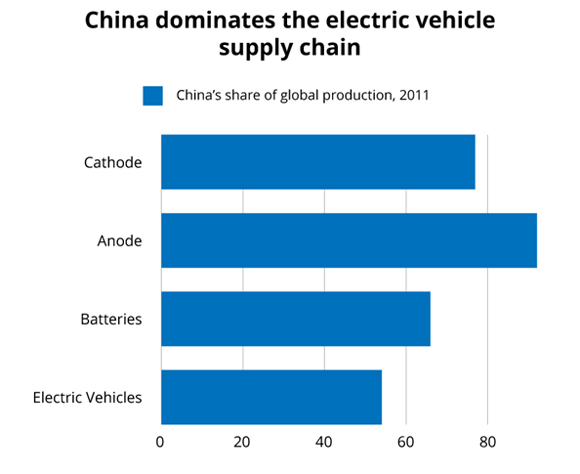

When it comes to electric vehicles and their supply chain, the figures are extraordinary.

|

|

| Source: International Energy Agency |

So, what could possibly go wrong with the green energy transition, and thereby our energy security, if it relies on good economic relations with China…?

Not much, I’m sure…

In 2022, as energy markets went haywire over the Russian invasion, energy stocks went ballistic. Nine of the top 10 performing companies in the S&P 500 were oil and gas stocks. The companies that could meet Europe’s demands when faced with (self-imposed) shortfalls out of Russia, in other words.

So, owning the companies that can provide the resources that China currently dominates would seem like a rather prudent hedge for a Chinese geopolitical crisis, at the very least.

Find out how you can do so, here.

Until next time,

|

Nickolai Hubble,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia Weekend