The US Fed held rates steady but flagged more tightening ahead. And markets finally caught on that the central bank is deadly serious about taming inflation.

So are we entering a new era of ‘higher for longer’ interest rates? We’re certainly adding a new term to the lexicon. You can’t read the financial press without coming across the phrase.

But as Greg Canavan and I mentioned before, when consensus forms in markets — and the same idioms are bandied about — it pays to think like a contrarian.

Rising bond yields suggest investors are more confident inflation can return to target without a sharp slowdown. But how confident should investors really be?

Milton Friedman once said it takes time for inflation to be cured and unpleasant side effects of the cure are unavoidable.

What’s not priced in?

The extent of those side effects.

Finally, we also discussed the recent rally of uranium stocks, the performance of cyclical sectors like travel (Qantas got a mention), and the coming hunting season for stock pickers.

Causes of inflation

I was reading Milton Friedman this week, who’s always insightful.

One chapter in his Free to Choose, co-authored with wife Rose Friedman, centred on cures for inflation.

The chapter is still fresh and relevant today.

Here’s the main idea:

‘Many phenomena can produce temporary fluctuations in the rate of inflation, but they can have lasting effects only in so far as they affect the rate of monetary growth.’

A historic detour serves as example.

Money has had many guises and forms through the centuries.

One was tobacco.

Tobacco was actually the basic money of Virginia and its neighbouring colonies, even decades after the American Revolution.

You could smoke it but also pay taxes with it.

But there was a hitch.

The original price of tobacco set in English money was higher than the cost — in English money — of growing it.

Money doesn’t grow on trees. But in colonial Virginia, it grew in tobacco crops.

And that’s where the trouble started. As Friedman summed up, the money supply grew literally and figuratively:

‘As always happens when the quantity of money increases more rapidly than the quantity of goods and services available for purchase, there was inflation. Prices of other things in terms of tobacco rose drastically. Before the inflation ended about half a century later, prices in terms of tobacco had risen fortyfold.’

Naturally, as prices of other goods in terms of tobacco soared, tobacco planters resorted to lobbying. And when that didn’t work, to violence.

At one point, desperate planters banded together and went around the country destroying tobacco plants.

The banditry was destructive enough that lawmakers decreed if ‘any persons to the number of eight or more should go about destroying tobacco plants, they should be adjudged traitors and suffer death.’

Growth of money supply the determining factor of inflation

The driver of inflation is the quantity of money per unit of output. If the growth in the quantity of money outpaces growth in output, prices will rise.

An important implication is the insignificance of productivity to inflation.

As Friedman writes:

‘What matters for inflation is the quantity of money per unit of output. But…as a practical matter, changes in output are dwarfed by changes in the quantity of money. Productivity is a bit player for inflation; money is centre stage.’

Productivity is vital for economic welfare, not inflation.

That’s interesting, especially in light of recent focus on wages growth and rising unit labour costs.

I’ve focused on that myself.

On productivity, Friedman further said:

‘Wage increases in excess of increases in productivity are a result of inflation, rather than a cause’.

In this view, rising unit labour costs don’t contribute to inflation, so much as they are a product of inflation.

And it’s not like Friedman’s idea is a relic of the ancient macroeconomic thinking.

A popular and recent textbook from Nobel Laureate Ben Bernanke says this:

‘Basically, inflation occurs when the aggregate quantity of goods demanded at any particular price level rises faster than the aggregate quantity of goods supplied at that price level.

‘In general, the only factor that can create sustained rises in aggregate demand, and thus ongoing inflation, is a high rate of money growth.’

And just look at the escalation in money growth across the world before inflation took off.

As you can see, a spike in monetary growth preceded a spike in inflation.

|

|

| Source: Bank for International Settlements |

The cure for inflation

What’s the cure?

Since money growth is the determining factor of inflation, the cure is declining money supply. Friedman didn’t sugarcoat it:

‘The cure for inflation is simple to state but hard to implement. Just as an excessive increase in the quantity of money is the one and only important cause of inflation, so a reduction in the rate of monetary growth is the one and only cure for inflation. The problem is not one of knowing what to do. That is easy enough. Government must increase the quantity of money less rapidly. The problem is to have the political will to take the measures necessary. Once the inflationary disease is in an advanced state, the cure takes a long time and has painful side effects.’

The sell-offs in recent days suggest investors are seeing in Powell the will to take the measures necessary.

Unfortunately, the measures are not without pain.

Friedman said ‘it takes time for inflation to be cured’ and ‘unpleasant side effects of the cure are unavoidable’.

Interestingly, Friedman warned not to embrace policies focused on raising unemployment and slowing growth as their end.

Both are not cures but merely side effects:

‘Slow growth and high unemployment are not cures for inflation. They are side effects of a successful cure. Many policies that impede economic growth and add to unemployment may, at the same time, increase the rate of inflation.’

Here’s an analogy used by Friedman.

You have severe appendicitis. The doctor recommends appendectomy but warns you must recuperate in bed for a specified time.

You decide on a better idea. Instead of the surgery, you confine yourself in bed for the specified time as the cure.

As Friedman writes:

‘Silly, yes, but faithful in every detail to the confusion between unemployment as a side effect and as a cure’.

Again, Bernanke, in his recent textbook, agrees on the cure:

‘Because ongoing inflation generally is the result of rapid money growth, the prescription for stopping inflation appears to be simple: Reduce the rate of money growth. Unfortunately, the process of disinflation — the reduction of the inflation rate — by slowing money growth may lead to recession.’

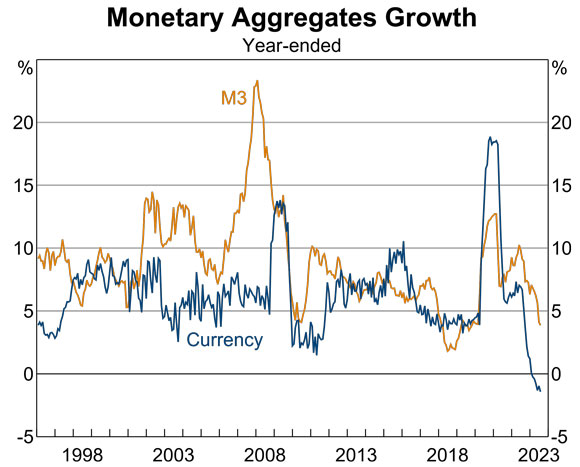

Money growth is now falling sharply in advanced economies.

Just look at this chart from the Reserve Bank.

The question is whether the deceleration of money growth will lead to recession.

|

|

| Source: APPRA; RBA |

There is no magic potion.

The cure for inflation will have side effects.

Is the market prepared?

Enjoy the episode and, if you do, leave a like and a comment!

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning