Welcome back! I hope you had a great holiday with family and friends.

Mine was pretty quiet. I spent much of it at the beach, whenever Melbourne weather allowed. Mainly paddleboarding (something I took up a few years back), reading, or watching the waves.

Waves at Port Phillip Bay are generally small, but — and I’m sure this happens in other parts of Australia — the waves at beaches like Ipanema in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, are a whole different matter.

The current is strong and the waves there are huge. So big in fact that to jump into the sea, you really need to get your timing between waves right, at the risk of getting wiped out…

It’s not surprising then that the word Ipanema really means ‘bad water’.

So if you want to go into the water there, you watch the waves come in, repeatedly, until the cycle becomes predictable. You wait for that short moment when the wave retreats…and then you make a run for it.

Speaking of cycles, my colleagues Callum Newman and Catherine Cashmore have spent years studying the land cycle. As they said recently, land prices can move in a very predictable way. It’s something they call the Grand Cycle.

And, right now, they see a land boom happening. For more info on the Grand Cycle and their five recommendations to take advantage of today, click here.

Cycles everywhere

Of course, cycles are everywhere in life, and another area where we see cycles is commodities.

The way commodity cycles go, there’s first usually an increase in demand where supply can’t keep up. This leads to shortages and higher commodity prices. This entices more companies to jump in to take advantage of higher prices. Then there’s a production boom, until supply catches up, and then comes the bust where prices come down.

Regular readers of this newsletter know I’ve been drumming on about lithium shortages. And, as we’ve mentioned before, battery and carmakers have been busy securing supply. Car companies are going to need massive amounts of battery metals to roll out electric vehicles.

But, of course, the energy transition will need plenty of other metals, not just lithium. Metals like cobalt, nickel, copper, platinum, and graphite to name a few.

And, for example, with graphite, things are already heating up with graphite prices climbing.

Take Syrah Resources Ltd [ASX:SYR] — two days before the end of the year, the Australian miner signed a deal with Tesla to supply them with four years of graphite.

As Shaun Verner, Syrah’s chief executive, told The Age:

‘If you look at the natural graphite market upstream today, the total global market is 1 million tonnes per annum … but by 2030, it will be somewhere between 3 and 4 million tonnes.

‘The demand growth is such that security of long-term supply of raw materials and finished goods is absolutely critical for auto manufacturers and battery manufacturers to ensure they have a reliable supply chain in the future.

‘We’ve been engaged with a number of potential customers for multiple years, but really the last 12 months have seen a significant escalation of commercial discussions.’

How to Limit Your Risks While Trading Volatile Stocks. Learn more.

Supply will need to ramp up

Of course, it’s not just electric vehicle makers. These metals are crucial for everything in the transition, like batteries for storage, wind, and solar. Especially as it’s becoming clear that the transition is only going to ramp up in the aftermath of the United Nations Climate conference COP26 last year.

Here is McKinsey:

‘Net-zero commitments are outpacing the formation of supply chains, market mechanisms, financing models, and other solutions and structures needed to smooth the world’s decarbonization pathway. Even as debate continues over whether the conference achieved enough, it is evident that the coming decade will be decisive for decarbonizing the economy. While every sector in the global economy faces common pressures—such as stakeholder and investor demands to decarbonize their own operations—metals and mining companies have been presented with a special challenge of their own: supplying the critical inputs needed to drive the massive technological transition ahead.’

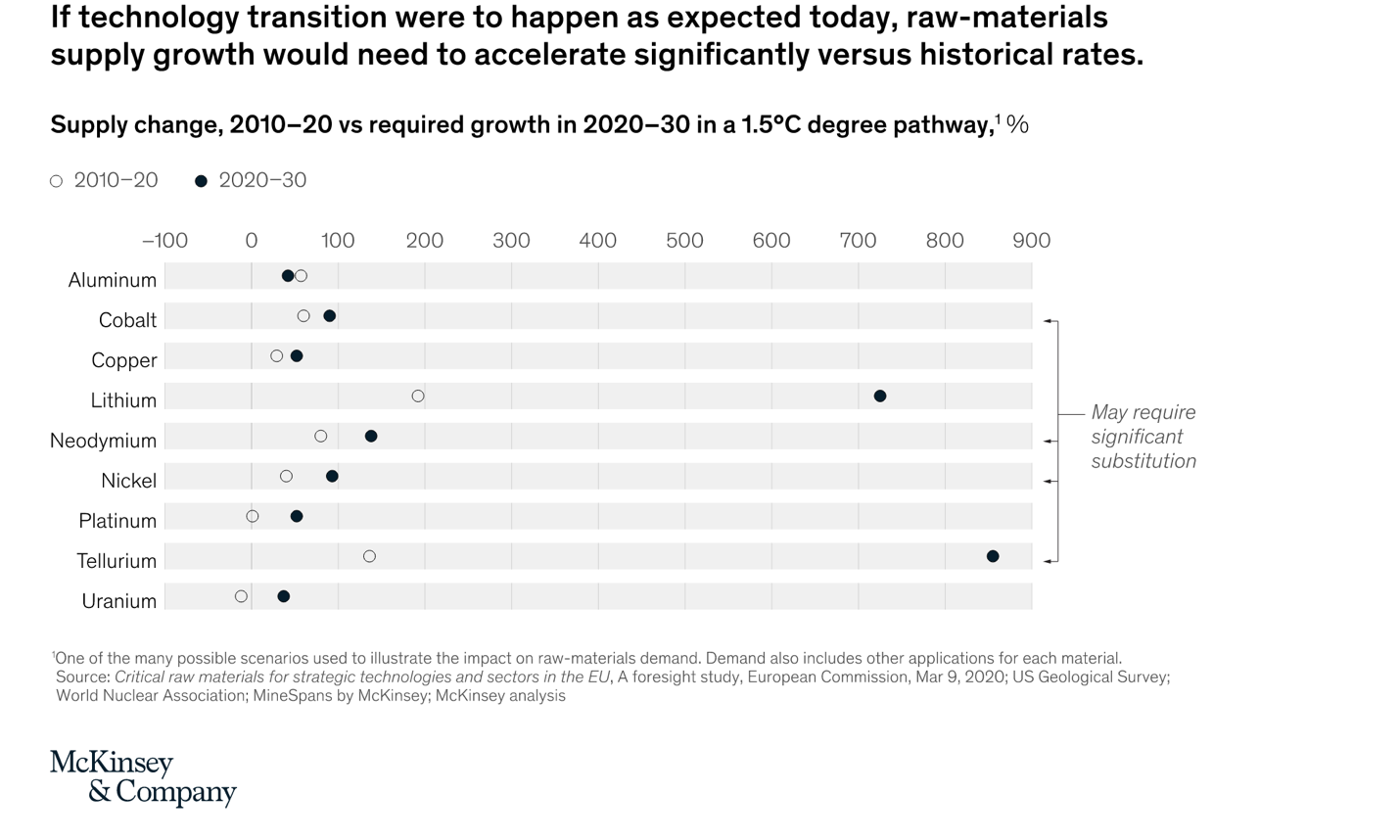

McKinsey concluded supply growth for all metals would need to grow ‘significantly’ if the world were to pursue a 1.5 degree scenario, as you can see below:

|

|

| Source: McKinsey |

So we could see some big moves in the metals needed for the energy transition in 2022, especially with the big threat of inflation hitting markets.

And it’s something that we’ll follow closely this year.

Until next week,

|

Selva Freigedo,

For Money Morning

PS: Selva is also the Editor of New Energy Investor, a newsletter that looks for opportunities in the energy transition. For information on how to subscribe, click here