Central banks in the high inflation economies have been unusually candid in admitting that rate hikes intended to destroy demand and squash inflation may result in recessions in their economies. That seems likely to be the case.

If so, the entire world may be following China toward a low-growth/low-rate outcome, which could be properly characterised as a global recession, or even a new depression.

Oddly, this recessionary outcome could result in reverse currency wars in which countries try to strengthen their currencies relative to the US dollar in order to lower the cost of dollar-denominated global commodities such as food and energy.

We’ll look at these developments on a country-by-country basis with an eye to global trends and global interconnectedness. In the end, readers will see that what happens in Europe (or China and Japan) doesn’t stay in Europe and affects us all. This will leave readers better prepared to deal both with the shocks and volatility that lie ahead.

Let’s take our trip around the world and see how it all connects.

First stop — The United States of America

As suggested in the introduction, the US economy cannot be considered in isolation — but it is the right place to start a global analysis. It is the largest economy in the world and the US dollar is the predominant currency for denomination of global reserves and global payments.

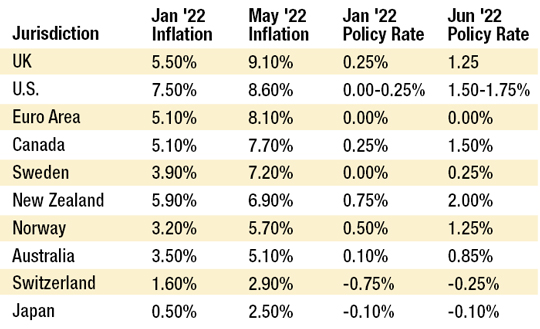

The chart below reveals that among major developed economies, the US has the highest inflation rate (8.6%) and the second-highest central bank policy rate at 1.75% (second only to New Zealand at 2.00%). That said, the US policy rate will be in the range of 2.25% to 2.50% after the Fed’s next FOMC meeting on 27 July:

|

|

| The euro has three policy rates; the data above represents the main refinancing operations rate. Inflation data is as of May 2022 except for New Zealand and Australia, where the latest quarterly data is as of March 2022. |

[Editor’s note: The chart this article was adapted from was published in 27 July 2022.]

What the chart doesn’t show is the recent performance of the US economy. It’s not good.

First-quarter GDP was negative 1.5% (annualised). The second quarter is just ending as of 30 June 2022, and we will not have GDP growth numbers from the Commerce Department until late July.

The best estimate available for second quarter growth comes from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, which uses available data that arrives monthly or periodically to forecast GDP in close to real time. That estimate is for 0.0% growth in the second quarter.

Combining the first-quarter decline with a second-quarter flat result produces an overall decline for the first half.

If actual second-quarter growth is finally reported as negative (which is no more than a rounding error away relative to today’s forecast), this would now put the US in a recession (as defined as two consecutive quarters of declining GDP).

The obvious question is: Why is the Federal Reserve raising interest rates if the US economy is on the cusp of a recession? The answer is inflation.

The Fed has a dual mandate to maintain price stability and reduce unemployment. These two goals are not complementary in the short run as economists wrongly once assumed. There are times when the Fed has to choose one goal at the expense of the other.

Right now, the US unemployment rate is at an extraordinarily low of 3.6% while inflation is the highest in 41 years at 8.6%. This makes the Fed’s choice easy — they need to crush inflation to avoid losing all credibility.

If raising rates to stop inflation causes unemployment to go up from 3.6% to 4.1% (as Fed Chair Jay Powell recently admitted may happen), then that’s an acceptable balancing act from the Fed’s perspective. Unemployment of 4.1% is consistent with the dual mandate, while 8.6% inflation is not. Higher rates and lower inflation are therefore the Fed’s predominant goals.

Left unsaid is whether higher rates and higher unemployment don’t just result in a soft landing for inflation but cause a hard landing and a recession. A hard landing is the most likely outcome; as noted, the US may already be in a recession.

Events could turn out much worse. A recession will hurt corporate earnings, which will cause the popping of asset bubbles, starting with the US stock market. A stock market crash could converge with a global liquidity crisis (that has already begun behind the curtain of financial plumbing as shown by yield-curve inversions in Eurodollar futures) to produce a combined recession and financial panic worse than 2008 and 2020.

In short, investors should be prepared to flip from 40-year highs in inflation to disinflation, and possible deflation, in a matter of months if the Fed persists in its rate hikes over the course of this year and into 2023.

Inflation hedges that are suitable now (including high-leverage and investments in stocks and real estate), may turn into a losing strategy as cash and Treasury notes come back into favour. Investors should diversify their portfolios to be robust to both outcomes and remain nimble when it comes to favouring one result or the other.

Next stop — the European Union (EU)

The European Union (EU) and the nearly conterminous Eurozone (consisting of countries using the euro as their currency) offer a more clear-cut example of trends developing in the US.

While the EU as a whole is not technically in recession, some major countries in the EU, including Germany, are quickly headed that way. Germany’s economy contracted 0.3% (quarter on quarter) in the fourth quarter of 2021 and grew only 0.2% in the first quarter of 2022. The most recent data indicates Germany may be experiencing negative growth again in the second quarter of 2022. Over the past nine months, the world’s fourth-largest economy is barely growing, if at all.

Still, inflation in Germany is 7.9%, which is dangerously high for any country but especially for Germany, which still has an historical memory of the hyperinflation during the Weimar Republic in 1922 and 1923.

Unlike the US, Germany doesn’t have a central bank that sets interest rates for Germany only; it must rely on the ECB to set rates for the Eurozone as a whole. The problem is the ECB policy process must consider weaker members such as Greece and Italy before embarking on a policy of rapid rate hikes in the same manner as the Fed.

This means that the ECB will have little impact on inflation by itself because its policy rate increases coming in the next few months will be too small and too late to impact demand. To the extent that inflation is supply-driven in terms of higher prices for oil, natural gas, food, and other strategic inputs, the ECB will have no impact at all.

What will subdue inflation is not central bank policy, but simple supply and demand as Germany discovers it cannot provide sufficient energy to keep factories operating and homes heated in the months ahead.

Germany has spent the last 14 years (mostly under Angela Merkel) shutting down its nuclear and coal-fired electricity generating capacity. This left it utterly dependent on Russia for oil and natural gas.

Now, those Russian supplies are prospectively being foreclosed by economic sanctions resulting from the War in Ukraine. German policy aside, Russia may reduce supplies in retaliation for German aid to Ukraine. Regardless of import sanctions or export reductions, oil and gas are both exploding in price because of supply shortages, general price inflation, and the war.

German officials have already announced a ‘red alert’ with respect to energy shortages. German inventories of natural gas are dangerously low. Germany will have to resort to rationing by this fall, which involves reduced manufacturing output, thermostats in homes set at 55° F, and rolling blackouts. This makes a recession inevitable and puts financial stress on German banking giants like Deutsche Bank.

As Germany goes, so goes the Eurozone. As with the US, we may see a situation of high inflation and rising interest rates flip into recession, disinflation, and rate cuts almost overnight. Investors need to prepare for economic whiplash. Again, diversification is the key.

Keep an eye out next Wednesday for part three of this series of articles.

All the best,

|

Jim Rickards,

Strategist, The Daily Reckoning Australia

This content was originally published by Jim Rickards’ Strategic Intelligence Australia, a financial advisory newsletter designed to help you protect your wealth and potentially profit from unseen world events. Learn more here.

PS: Due to the national public holiday, there won’t be a Thursday edition of The Daily Reckoning Australia this week. We’ll be back to our regular schedule on Friday, 27 January.